Documentary film-maker Arthur Cary tackles difficult, often harrowing subjects, with great sensitivity. He discussed his work – including feature-length Holocaust documentary The Last Survivors – with fellow film-maker Anna Hall, creative director of True Vision Yorkshire, at the RTS Student Masterclasses.

From comedy to docs, via reality TV: “With my writing partner from university, I was writing script-based comedy… we got close a few times to getting things away but it wasn’t quite working,” recalled Cary.

He landed a job as a runner at Endemol, working on BBC Three show Celebrity Scissorhands and then Big Brother: “I exploited every connection I had at Endemol and got a job at North One, which used to make a lot of Cutting Edge [documentaries] for Channel 4.”

First break: “I developed an idea for a Cutting Edge about four eight-year-olds going to boarding school and worked on [Leaving Home at 8] as an assistant producer (AP).”

Ideas: “I generated more ideas when I wasn’t directing than [now]. When you’re directing, you’re so focused on what you’re doing and when you come back up for air you tend to run out of time to develop ideas before you get back into making the next film… As an AP, I developed three or four things that were made by other directors that I could work on – it’s a really good way to get yourself noticed.”

Self-shooting: “I was able to shoot taster tapes when I was working in development… to work up my skills. On [Leaving Home at 8]… we had to split stories, so even though my shooting wasn’t brilliant, I had the opportunity to film for broadcast… You need to get your hands on a camera and practise as much as you can – and be open to criticism.”

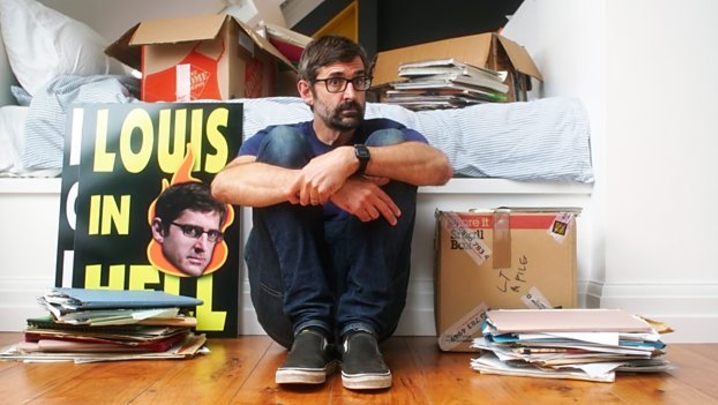

Louis Theroux: Savile was Cary’s first major directing job, a BBC Two doc that revisited Theroux’s relationship with the monstrous DJ, first captured a decade and a half earlier in When Louis Met… Jimmy: “Louis genuinely didn’t know how he felt about their history and whether he should have… worked Savile out… [He]… had the wool pulled over his eyes by Savile in the same way the public did. To explore how that had happened to him was a way to explore how Savile had done it to everybody.”

“You get very emotionally involved and you need to harness that – films that I make are as much a reflection of my emotional response to a subject as they are an intellectual response…. So, you don’t want to shut off emotion; equally, you need to be able to function while you’re making films.”

“You’re constantly negotiating access. There are times where it looks a little bit dicey, maybe you have upset people by filming what they didn’t want you to film, but it’s [about] relationship building… you need to find a rapport … You spend more time with contributors not filming than filming, so by the time you pick up the camera that relationship is fairly solid.”

Maintaining integrity with contributors: “[They] watch it before it is broadcast… they don’t have editorial control, but they can check for factual inaccuracy and fairness… You feel a responsibility to make something they feel is fair and an honest reflection of [their] story.”

BBC Two feature-length film The Last Survivors: “I was quite intimidated by it… I’m not Jewish, so I felt a responsibility as an outsider making this film… You’re really struck when you start making this sort of film at how important it is to the community to make films that chime with how they feel and do justice to the subject.”

Feature documentaries suit “the style of story-telling that I like [which has] a long-form, narrative arc … They feel like a bit of a hybrid, [using] drama tropes in the service of documentary story-telling. The integrity of the story is always at the heart but the range of tools that you have at your disposal to tell the story [is wider].”

You need to be obsessive as a documentary filmmaker – you’re thinking about it 24/7… there’s no separation and that can be tiring. You need a break… and start engaging with the world [again]… to work out what want to make a film about next.”