Twenty years ago, it would not be until the evening that the news of the day filtered back to UK audiences. By 9pm, dusty news journalists scattered across the globe would have filed their stories of political upheaval or social unrest, ready for an audience of yawning Brits, keen to know what was happening at home and around the world.

Then with the advent of 24-hour news channels and the internet, news became more immediate. The only delay between a story breaking, and you being able to read about it, was the time it took for a journalist to get on the scene and report.

But today even that is too slow. Now, the world is at your fingertips. News organisations can send push notifications to phones everywhere instantly; Twitter and Facebook allow users to engage in the conversation as it’s happening. And the earliest reports are no longer the ones you read on news websites. They’re remarks from ordinary, local people, whose first response to an unfolding scenario is to get out their phone and share the news. It doesn’t matter if an incident is unfolding in Cairo or Croydon or Canberra, once it’s online it’s a global event.

Charting the change

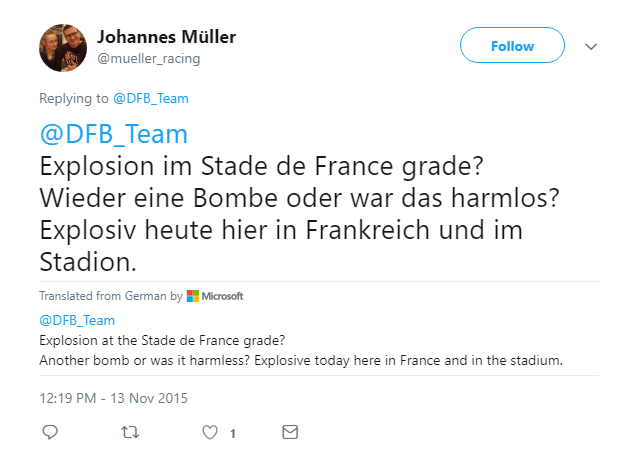

During the Paris terror attacks on 13 November 2015, the first report of an incident came at 21.19, when an explosion was heard outside the Stade de France and German user Johannes Muller tweeted the German team, asking “Explosion at Stade de France? Was it a bomb or was it harmless?” Media around the world was slower to respond, and also reported that the explosion came a minute later, at 21.20.

Later, 21.40, at the Bataclan concert hall during a gig by American band Eagles of Death Metal, three gunmen emerged from a black vehicle and entered the building, firing indiscriminately into the crowd and taking hostages. Shortly afterwards user Stephane Hannache used Twitter’s live streaming platform Periscope to share live images of the exterior of the scene with the world, reaching tens of thousands of viewers before the platform crashed.

So what is the point of sending a well-equipped team of highly skilled professional journalists – at great expense – to some of the most inaccessible places around the world, if anyone with a smart phone can do the job?

BBC News Correspondent Orla Guerin sees the challenge, but doesn’t see it as a threat.

“There’s an immediacy now, and people have access to information in a way that they never did before. We’re in an era of 24-hour journalism. [However] I very much believe in the primacy of trusted sources.”

The point she makes is a key one: particularly during major unfolding events, urgency can lead individuals and organisations – accidentally or malignantly – to use social media to disseminate false information, which is then mistaken for truth.

Following the terror attack in Manchester in 2017, online trolls began sharing images of fake ‘missing people’, adding to the confusion of genuine attempts to locate family and friends. John Jurasek, a 20-year-old American with a popular YouTube channel TheReportOfTheWeek, was following the story unfolding in Manchester he saw his own face on Twitter, listed among those missing following the attack with the caption “He’s not picking up my call! Please help me!” He took to his YouTube channel to assure friends, followers and family that he was alive and in the US. There were many comparable stories in the confusion that followed the attack.

What has gone wrong?

“There is a very big gulf between what is easily available on social media, and the quality of journalism that respected news organisations are still doing,” Guerin insists.

“People need to be conscious [about] what they read on social media. By all means read it, but try and make sure that you’re also getting an informed overview from some organisation which has invested the time in sending people there.”

False information abounds online. Guerin recalls a recent IS attack in Sinai, Egypt: “We were not allowed to enter Sinai, so we couldn’t go there and film our own material.” Instead they found some User Generated Content (UGC) online which purported to show the explosion of the mosque. However on closer analysis – looking at the accents, dress style, weather and local landmarks – they came to realise that the footage was false. It was actually filmed two years previously in Syria.

“There is a reason why people should turn to trusted sources,” she says. When the BBC uses UGC, she says, “we verify it. We don’t use it if we haven’t.”

"If you want news that’s straight, you have to buy it" - Stuart Ramsay, Sky News

Sky’s Chief Correspondent Stuart Ramsay agrees. “I think people will stop listening to Twitter as if it is true, and accept that you’re going to pay for it [quality news] in some shape or form. If you want news that’s straight, you have to buy it.”

Earlier this year the Edelman Trust Barometer reported that in the UK, public trust in social media has fallen to an all-time low, with less than a quarter of the British population trusting social media. Traditional media on the other hand, saw a 13% rise in the past year to over 60%. The study found that around 70% of British people do not believe that social media giants are doing enough to stop illegal or unethical behaviour on their platforms.

However as trust rises in traditional media, one third of Brits continue to report that the news is too one-sided or biased.

Righting the ship

So what can be done? Journalists believe that if they can improve public trust in their output by demonstrating the value of what they do, they can secure news against the threat posed by social media. However countering those low levels of trust remains a problem, and one compounded by an ‘Us vs Them’ tension between media and those in power.

For Matt Frei of Channel 4 News, that question is a fundamental one for the future of the profession. “For us journalists, the tricky balancing act we have to perform in the next few years is being aware why we no longer share the same assumptions – about wealth creation, liberalism, the nature of democracy - … and at the same time trusting our instincts to basically call something out when it needs to be called out,” he told the RTS last year.

The public need to believe that journalists are the best, most impartial, most accurate, and most reliable source of news, so rebuilding trust is key. It means, he says, “we’ve got to be really clear on our facts. And it probably means we’re going to have a lot of really boring journalism. Because ultimately it’s the facts that matter.”

However countering an entrenched belief that social media can provide a clearer, rawer story than journalists is difficult. Honest mistakes can be presented as deliberate misinformation. In an RTS interview last year, Newsnight’s Emily Maitlis recalled her 2016 US election coverage. “You have to really check that you have got your facts right. If you say New Hampshire and you mean Rhode Island then they go ‘that was a load of lies. That never happened in NH.’ ‘Of course! The whole story was right but I said Rhode Island instead of New Hampshire!”

Recently, in a heated encounter with former White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer, she held him to account over the claims in his first briefing that Mr Trump’s swearing in saw the “largest audience to witness an inauguration, period.” Responding to questions accusing him of “corrupting discourse for the entire world by going along with these lies”, Spicer replied “you’re taking no accountability for the many false narratives and false stories that the media perpetrated,” essentially a cry of ‘Fake News’, Maitlis notes.

“There’s always been a tension between those in power and those who hold power to account,” Maitlis told the RTS in 2017. “What we’re seeing now is just a more blatant disregard for it.”

RTS winner Tom Bradby of ITV News added in an interview in 2017, “[The public] have got to trust your motivations and they’ve got to trust that whatever you might privately feel about every subject, that’s always going to be overridden by your desire to nail the truth.

“The BBC, Channel 4 News, it’s the same with all the places: the single thing that people in these newsrooms share is the desire to ail the essential facts, and the most reasonable analysis of those facts.”

The only solution, they seem to agree, is to work to the highest standards and wait until that trust returns. Audiences will come to value is the expertise of the journalist, Ramsay maintains. “Journalism was a profession once upon a time. It stopped being one, but it was one, and I think it might start to come back again,” he says.

“There’s nothing independent that isn’t paid for. The quality can’t be guaranteed if it’s not being done by professionals, and professionals have to be paid.”

Until then, Frei says, “We’ve come to such a state that it is possible where, however nicely you put your objections to these untruths, and however sober the presentation of the facts is, you are still not going to be believed. There’s not much you can do about it. You can’t stop pointing it out, because at some point, maybe, you’ll be believed."