Peter Bazalgette identifies the threats to Britain’s public service media and suggests how the UK can harness its creativity.

Sir Peter Bazalgette – known simply as “Baz” to colleagues and so many others across the creative industries over which he has towered for the past four decades – recently stood down as Chair of ITV, marking the end of another chapter in his long career.

As a pioneering independent producer, he formed Bazal Productions, creating such innovative shows as Ready Steady Cook and Changing Rooms. He is a former Chair of the Arts Council and English National Opera and a former President of the RTS – and the man credited with bringing reality TV to the UK in the form of Big Brother, and, with Food and Drink, inventing the celebrity chef.

But in an evening hosted by the RTS, it was clear that Bazalgette’s eye is not on the past but the future of TV, specifically safeguarding the position of public service broadcasters within that future.

Having previously defined public service media as “programmes made for us, by us, about us”, Bazalgette made clear his concerns for the future of PSBs, in both legislative and commercial terms. “Every year, the schedule gets slightly smaller in terms of the number of people watching it,” he began, citing the rise of BBC iPlayer, All 4 and the forthcoming streaming service ITVX. The idea of “being in broadcasting” was otiose.

“Now, they have to get those services carriage on about 40 different platforms, including Sky, Virgin, Amazon, Apple TV+, and they need to get them carriage and prominence on Samsung and LG connected TVs.

“All of those [operators] are run by foreign companies that don’t really care what the ecology of our broadcasting is. And they’re all operating via the internet, which is unregulated, and they can name their own terms.

“They might take an enormous amount of revenue from those services, and not share the data about who is watching – and if you don’t know or don’t have the data today, you’re dead.”

Bazalgette referenced the broadcasting white paper, published in March, which included government commitment to a law that, he explained, “in principle updates the 2003 Communications Act” – namely, protecting access, prominence and fair value.

Whereas the battle in 2003 centred on a channel’s position on the electronic programme guide (EPG), Bazalgette described how, with so many platforms today, it is more likely to be a competition for eyeballs between traditional content, gaming and other products.

“I’m not knocking that, that’s up to them, but you won’t get prominence,” he warned, hence the need for legislation to ensure prominence for the PSBs on those platforms.

However, he rued the inclusion in the white paper of the proposed sale of Channel 4, which meant that all the other issues were sidelined: “The prominence issue is the existential one, far more important than the Channel 4 privatisation, whatever your view, pro or anti – far more important.”

He pointed out that ITV has to apply next year for a new PSB licence. “Why would it apply if it doesn’t know what the terms are? Have we got the prominence, or have we not got the prominence? So that’s the story and that’s why I say it’s the existential issue.”

Bazalgette reflected on the need for “programmes made for us, about us, by us” to support cultural, social and political life in the UK. “A healthy national identity has to talk to itself; you need a national conversation, you need to examine things. While they have lower viewership now than they did 10 years ago, I think the soap operas do this: they examine social issues, things we care about, or we’re not certain about, things we’re angry about – and that’s really important.

“You don’t get that from internationally appealing programming, or programming that was made in another country. So it is important to have a healthy ecology that delivers these programmes and not just one that delivers the wonderful wealth of content that’s also available to us on the international streamers.”

Having considered the legislation required to protect the PSBs from this “existential threat”, Bazalgette moved on to the financial challenges of creating the kind of content he was referring to.

“This is an issue for the whole of Europe,” he said, citing the recent attempt, ultimately aborted, to merge France’s TF1 and M6 channels. “If your future success depends on a streaming service, the key to a successful streaming service is, a) having a big enough origination budget to commission new programmes (because that’s what sells subscriptions or gets eyeballs if it’s ad-supported) and, b) having a big enough catalogue to keep subscribers happy.

“So the question is: how can European broadcasters, PSB or otherwise, compete with international streamers in the future? It’s probable that each country could have one or two successful streaming services like that, but probably not four or five. This suggests that, to meet the long-term commercial challenge, there needs to be consolidation.”

However, he said: “Consolidation between commercial broadcasters in the UK simply wouldn’t be possible at the moment because the media buyers would fight it all the way.”

Asked if a privatised Channel 4 could fit quite happily in the portfolio of, say, ITV, Bazalgette didn’t blink. “Well, it seems to me that is one possible consolidation, yes. How extraordinary you should mention it! But if you think I’m going to speculate on whether it will happen – or should happen – I would be tying the hands of my successors at ITV. Which I don’t intend to do.”

As an example of “when the regulator was unable to look at the road ahead”, Bazalgette recounted the story of the dead-on-arrival Project Kangaroo. The regulator “made the worst decision a regulator has ever made, it stopped ITV, the BBC and Channel 4 setting up what was essentially a streaming service between them in 2009.

“That streaming service today would be worth billions and would be competing worldwide, but we were told we weren’t allowed to do it, because the regulators were looking backwards.

“They didn’t understand where the business was going. So I’m saying: let’s not do that again, let’s not tie our hands behind our back. How many people are listening, I’m not sure.”

Persuaded to look back briefly on his own pursuits with Big Brother, Bazalgette described the show, with notable understatement, as “innovative in a number of ways”. He specified: “A streaming of the channel, which [also showed] the edited version, the telephone, where you could vote, [which] linked different media together, in a visceral sort of way.”

He added that no new television genres had been created since then, with the innovation happening instead in the means of distribution, production and technology. He went on to consider the consequences of this for the workforce: “The BFI issued a report the other day that said 41% of the 16-year-olds polled did not know there was a career in the screen industries.

“Now, we have got every studio full, we’re short of carpenters, real-time game engineers, make-up artists. We’re short of every conceivable skill that you need to make a movie or TV drama, and we’ve not got the message over to schools that these career paths exist.”

(Credit: RTS/Paul Hampartsoumian)

Bazalgette also reflected on his role as Co-Chair of the Creative Industries Council, and his hopes for the creative sector to be taken more seriously by the Treasury. “As a country,” he said, “we over-inform on traditional sectors such as manufacturing in terms of data, and we under-inform on sectors like the creative industries.

“The definitions of R&D are not appropriate to the creative industries, so we don’t qualify for some of the tax credits we could otherwise get. For instance, a lot of the R&D done in the television industry, such as when we’re developing TV shows, never appears in the Office for National Statistics [figures] on R&D. Which is ridiculous, but it shows how the country, the mechanisms of government, the statistical services, have not caught up with where the economy is going.”

At the end of an evening devoted to his vision of television’s future, Bazalgette was asked which TV show of the past he would like to have claimed as his own. “No question, no contest,” he answered immediately. “Antiques Roadshow. Completely brilliant show.”

Why so? “It’s a show that combines national identity, local identity, personal history, national history, craftsmanship, but also avarice. It’s an irresistible combination.”

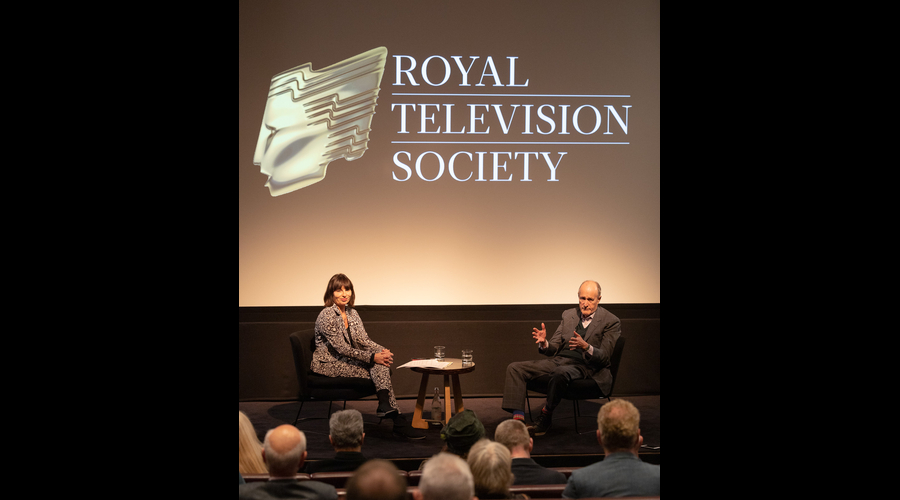

Report by Caroline Frost. Sir Peter Bazalgette was in conversation with Theresa Wise, RTS CEO at the May Fair Hotel, central London, on 13 October. The producers were Steve Clarke and Sue Robertson.

Regulation of the internet

‘It’s bloody difficult,’ was Bazalgette’s reply when he was asked if he thought politicians were dragging their feet on the Online Safety Bill. ‘The internet is an industrial revolution, it’s driven a coach and horses through all those norms, and it’s a massive challenge to civil society and we’ve not yet…. We’re only 15, 20 years into an industrial revolution, we haven’t yet worked out how to do it.

‘The truth is, they can pass any law they like, it doesn’t make the internet easily regulated.’

As for the tensions between protecting free speech and effective legislation, Bazalgette said that the online giants needed to try to be responsible for the content that appears on their platforms.

‘Up to very recently, they’ve been arguing, “Oh no, we’re just a platform, stuff comes through, we’re not editors, we’re not publications, we don’t have responsibility, we don’t do that.…” Well, it’s sort of not true, is it, but they’ve got to learn how to do it, haven’t they?’

Asked by an audience member at what stage a platform becomes a broadcaster, he replied that they could be easily differentiated: ‘Either you’re distributing other people’s signals or you’re not.’

For a streamer such as Netflix, he explained: ‘It’s not a platform, it’s a distributor of its own signal. Platforms are the people who are aggregating different services: so Sky is a platform, Netflix is on Sky, but Netflix doesn’t host other people, so that’s the difference.’

The future of the BBC

Never mind the funding model, whether it’s voluntary subscription, an addition to council tax or direct taxation, the bigger question, according to Bazalgette, is why do we want the BBC?

His answer: ‘Because it’s such an extraordinary organisation, because it’s such a brilliant invention, because it’s our great calling card around the world and because it’s an amazing reservoir of talent.’

For Bazalgette, the key aspect of keeping the BBC publicly funded is its paradoxical remit in holding governments to account: ‘The idea you should have a compulsorily funded broadcasting body that has the specific remit of holding the government to account, seems to me to be one of the most sophisticated and laudable descriptions of a sophisticated liberal democracy….

‘We have to defend these things, and that’s why it should have a funding mechanism that keeps it independent.’

Referring to BBC Director-General Tim Davie’s remarks at the RTS London Convention – that commercial revenues are dwarfed by licence-fee revenue, Bazalgette said that, whenever it enjoys commercial success, the BBC is accused of ‘being too commercial’.

He added: ‘Tim is preparing everyone to understand that there is a limit to what you can make – and will be allowed to make by competition authorities – and, therefore, he is reminding people that the hypothecated funding is still very important.’

‘He needs to make that argument and I think he has put it correctly.’

The future of Channel 4

‘Whatever the rights and wrongs, it wasn’t properly debated,’ said Bazalgette of the proposed sale of Channel 4. The arguments over the state-owned broadcaster have ‘become a dangerous distraction – and I think the Government should drop it,’ he added.

He praised Channel 4’s recent move away from London to centres in Bristol, Leeds and Glasgow.

Leading a DCMS review of the creative industries in 2017, he had suggested investing in geographical clusters. ‘We put £50m into nine creative clusters. They’re four years old now and cover AI, fashion, screen tech and video games, in different parts of the country.

‘I thought it would attract another £50m investment from the private sector – it’s attracted more than £200m. Whenever any of the public sector broadcasters clusters its talent, exciting things happen; more companies set up, more growth takes place. So, I think it would probably be quite good if Channel 4 pursues that idea.’

Remembering his own success at Channel 4 producing programmes such as Deal or No Deal and, of course, Big Brother, Bazalgette said he understood why the broadcaster needed to be pragmatic.

‘It has to keep a certain amount of share because it has to earn a living and so it has to bolster its schedule with things such as Bake Off,’ he said. ‘Also, it is buying sport at the moment because it has got a bit of a surplus… so I wouldn’t knock it, but I think it needs to keep an audience and it’s more and more difficult to do it.’

All photography by Paul Hampartsoumian