The Royal Television Society's Early Evening Event at the Hospital Club saw Labour's Shadow Culture Secretary, Chris Bryant talk about his vision for the future of the BBC. Read his full speech here.

Nobody can now be in any serious doubt that the BBC is under siege. It started the day after the election, the Daily Express headline made clear, “BBC must now pay the price for its blatant anti-Conservative bias”. Since then we have seen constant anti-BBC briefing to a very compliant press. Then the Chancellor raided the BBC coffers to pay for the Government policy of free television licences for the over 75s in exchange for the promise of a possible CPI increase in the licence fee from 2017 – and briefed the news ahead of the Budget to The Sunday Times.

This weekend we learnt that the Prime Minister intends to use the Charter renewal process to stop the BBC making popular Saturday night entertainment shows like The Voice and that the CPI increase may well not go ahead. Yesterday’s front page of Metro screamed ‘Axe The Voice and TV licence fee, BBC is told’. Far from being the consensual politician we had grown used to in the Select Committee John Whittingdale is revealing himself to be the true ideological son of Tebbit and Thatcher.

Maybe it’s the excitement of unexpectedly winning the election that has got to them. Maybe they’ve just had an overdose of testosterone, but with Javid, Osborne and Whittingdale each taking chunks out of the BBC it is all the more important that we remind them that they do not carry the nation with them on this particular bully crusade. And we should look to the future. With fixed term parliaments we should consider an eleven year Charter to take the next renewal out of the heat of battle and well beyond the 2025 election.

That is not to say that I think the BBC doesn’t need reform. I remain a critical friend. I will, for instance, continue to criticise its record on diversity. Of course the BBC cannot stand still. It has to embrace change and reform, because change is intrinsic to broadcasting. So intrinsic that the very word ‘broadcasting’ seems old hat. The idea that a channel would beam into millions of living rooms so that countless families would enjoy the same programme simultaneously let alone that they would watch two or three programmes in a row on the same channel has a rather quaint old-fashioned Two Ronnies ring to it.

We now watch audiovisual content in myriad ways – on tablets, on smartphones, through Youtube, Facebook, newspaper web-sites. The remote control, the video recorder, the hard disk recorder, iPlayer have successively changed our habits. Even the grammar of that content has changed. The 26 minute comedy, the 90 minute movie, the game show, the talent show and the Bank Holiday weekend two-part police drama are all still around, but some of the best loved new content is rough and ready, much of it is in a very short format and interactive. It’s a far cry from the stately cadences of Richard Dimbleby at the Coronation.

But even here we should be careful. The new means of watching catch-up TV is adding audiences to must-watch shows so that far from disappearing from view, the shared national TV experience is still very much alive.

Five Reasons

So against this background it is right, in the words of Julie Andrews, to start at the very beginning and ask what on earth is the point of the BBC? And what will be its point in 2027?

I offer five reasons:

First, Broadcasting the BBC is an intrinsic aspect of modern life. It’s the fifth estate. 75% of people in this country look to television for their news, compared to just and 41% who use the internet and a similar number who rely on newspapers and a great many of them look to the BBC for both those services. At key moments broadcasting it helps define us as a nation – and, I would argue, as a united nation. Think of the bombings in London. Or the week that Princess Diana died. Or the General Election. Or the Olympics. In times of sorrow and of celebration it can be the glue that holds us together and I for one think that is a public service role.

Second, broadcasting tends towards monopoly and vertical integration. It costs a lot to create a single hour of drama and to broadcast it to one person, but it doesn’t cost much more to broadcast it to a million or a million and one. It uses a scarce resource, spectrum, which is why it is so tightly regulated in every country – but the evidence from countries as diverse as Italy and Australia is that if you want to ensure a multiplicity of voices you have to retain a strong independent public service broadcaster. Otherwise we simply surrender our cultural life to the multinational players.

Which takes me to my third point. Of course the BBC shouldn’t just confirm us in our parochialism. It needs to show us the whole world and expose us to things we had never even dreamed of in our private philosophy, but people in every country also want programmes that reflect their life. It’s a form of patriotism. They like seeing their city or village and people like them on television and hearing voices like theirs on radio.

But ours is not a large market. In 2013 our total TV revenue came to £13.4 billion, compared to £18.9 billion for Germany and £110 billion for the USA. It is often thought that US programming dominates western markets, but of the top two dozen TV audiences ever in this country only one was American, when 21.6 million tuned in to Dallas to find out who shot JR Ewing on 22 November 1980. All the other programmes were home-grown – Eastenders, Coronation Street, Panorama (well it was the Princess Diana episode), Only Fools and Horses, To the Manor Born and the 1967 Miss World Contest (from London). The same goes for the top ten audiences for world events – still the biggest UK TV audience was for the World Cup Final in 1966 on the BBC and ITV.

A key part of what makes home-grown programming in every genre possible is national subsidy, as in Germany and every other smaller European market Italy, Spain, the Benelux and Scandinavian countries. The market simply can’t provide that British programming in some genres. It is a delight to see how Classic FM and Sky Arts have flourished, but they have the advantage of a very high value demographic. By contrast, children’s programming is now almost entirely the preserve of the BBC, which spent £84m last year, representing 97% of UK PSB children’s programming according to Ofcom’s latest report.

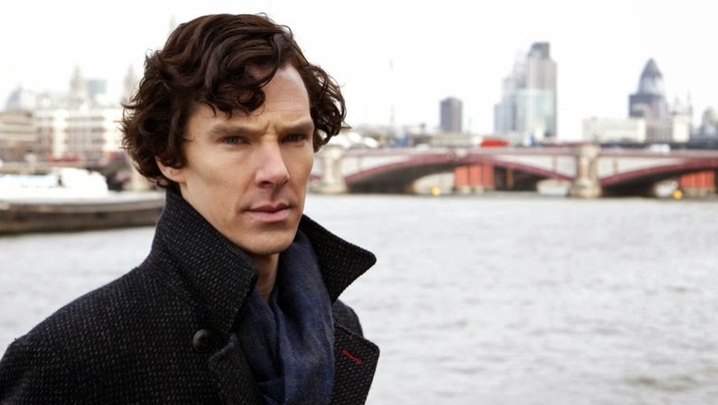

Fourth. We have a reputation to live up to. I don’t think I’ve ever met a foreign diplomat or politician who hasn’t praised the World Service or the BBC for its impartial news. Unlike any other country in Europe we are a net exporter of programmes too - Sherlock was sold to 224 territories and had 67 million hits on China’s digital platform YouKu,Strictly or Dancing with the Stars is sold to more than 40 territories, whilst Doctor Who’s 50th anniversary was simulcast in 98 countries and 15 languages. Our broadcasting is a key part of our international diplomacy – our soft power – and I am mystified that a Conservative government above all would want to limit the BBC’s news output to an pared down web-site.

Incidentally, sometimes that praise is unjust. One Belgian cab driver once told me he loved all those great BBC programmes – like Inspector Morse, Prime Suspect and Brideshead Revisited, all of which were Granada productions.

The truth is we do this well.

Fifth. If the BBC were not to exist there is no evidence that other broadcasters would invest more in production. Advertising revenues would be the same and the majority of watching on pay tv platforms remains with the public service channels. Viewers would have to rely on US and other imports.

When you consider that Ofcom’s recent review of PSB argues that there has been a £400 million fall in investment in new content, the very idea that the BBC should be cut down to size is madness. This is a point that I think the ideo-tories like Gove, Javid and Whittingdale simply don’t get – the BBC is the cornerstone of the creative industries in this country and the creative industries in turn are not just a pleasant added extra to the UK economy, a luxury if you like, they are the powerhouse of our future prosperity.

They represent one in eleven jobs, they bring in £76 billion a year, they enhance our reputation overseas, they are intrinsic to our whole added value economy and they have seen growth year on year well ahead of the rest of the economy.

Thanks to its historic role as a driver of broadcasting innovation and thanks too to the series of partnerships the BBC has engaged in over recent years, the BBC is right at the heart of the creative industries. It’s not just keeping 9 orchestras running, or breaking new acts on Radio 1 or Jools Holland, or investing in British film or live music.

The BBC cooperates with its commercial competitors, it commissions work from a vast range of production companies and it gives a platform for actors, directors, singers and artists whose work will regularly take them from the very commercial to the remarkably niche.

The point is that the British creative industries cohere as a balanced ecology with the BBC at its heart. Only a madman would take an axe to the tallest tree in the middle of the forest and not expect to do serious harm to the whole of the forest.

The BBC doesn’t harm the wider industry, it foster it; it creates a competition for quality; and its £3.7bn from the licence fee is the largest investment we make in the arts.

Scale and scope.

There are those who argue that the BBC is too big. ‘Imperial’ was the word used by George Osborne. I guess he meant ‘too big for its boots’. That seems to be the Prime Minister’s view too.

They say that the BBC should limit its ambition. The Secretary of State thinks it is ‘debatable’ whether the BBC should even make Strictly Come Dancing, let alone show it on Saturday night and his Charter Renewal is apparently meant to be a root and branch review of the scope and scale of the BBC.

Needless to say, this is a popular view with some of the British press, especially the press with their own direct or indirect commercial interests. But it’s a mistake. And it’s not very Conservative.

Website

Some point to the demise of local newspapers and point the finger at the BBC. But the reason the Rhondda Leader has fallen from 30,000 to 3,000 in fifteen years is not because of the BBC. It’s because people used to buy the paper to buy a car, a house or a pet or to see photographs of their child at school on St David’s Day.

All that has changed – and Facebook is a far more reliable and instant source of news than most local newspapers. If anything I would be critical of the BBC’s inability to spread its newsgathering wings outside the M25 or north of the M4.

So, I disagree with the Prime Minister. John Birt was absolutely right to build a strong BBC internet presence. Rupert Murdoch was wrong to claim that it was illegal state aid. Whittingdale should remember that more Americans visited the BBC web site on September 11 than any US web-site – and did so again on the day of the Boston marathon bomb.

Audiences continue to move online. The BBC of 2027 can only manage that transition with a strong internet presence. I find it inconceivable that anyone other than a hard-line free marketer would want to lop that particular branch off the BBC

Popular programmes

Take the case of sport, too. Most sport could be shown behind a pay-wall or on commercial free to air television. It would be commercially viable. But there’s a moral question here. Who has created the value in that sport? In part, the governing body of the sport. They’ve promoted it and maintained its reputation. In part too the broadcasters who fashioned a way of showing the sport and retaining people’s interests. But in the main the value is created by the fans.

It’s patriotism of the very best sort that inspires audiences to watch the Olympics or Wimbledon, which is why we legally insist that certain sporting events should be on free to air television. It’s our national identity that builds that value – and that shouldn’t just be for sale to the highest bidder.

But it’s more than that. A BBC without sport would no more be a national broadcaster than a BBC without a serious evening news bulletin.

This goes to the heart of the issue. The golden thread that runs through the BBC is that everyone gets something out of it because everyone has paid for it. You might want Pappano on classical music. Or a searing documentary on Syria. Or Sun, Sex and Suspicious Parents. Or Eastenders. Or Wimbledon.

Yes, it’s the BBC’s mission to do something more than just chase audiences and I think the BBC could take the foot off the cross-promotion pedal, but popular programming is what justifies the licence fee to the vast majority of my constituents. The ‘entertain’ in Reith’s ‘inform, educate and entertain’ isn’t just an afterthought. When asked to choose from some words describing what the BBC’s mission should be, over 6 in 10 people chose ‘entertain’, more than any other.

Making the good popular and making the popular good. It cannot just be posh TV at the public expense. A universal service that binds the nation together, the BBC can remain our cultural NHS.

That is why, although I remain open to the idea of the household levy I believe the licence fee should remain for the full period of the Charter with the CPI inflation rise as promised.

Governance

I don’t think there is anyone who now believes the Governance structures of the BBC are fit for purpose. The Select Committee didn’t and it seems the Government doesn’t either.

The events of the last two weeks when the Chancellor mounted a stick up job on the Director General and the Chair of the Trust prove the point. There was nobody independent enough of the BBC or of the government who was prepared to issue a word of dissent.

The Chair of the Trust issued a letter after the event objecting to the process, but since it was exactly the same process as was used in 2010, you might have thought they’d have made clear their objections in advance and in public. The end result is that the Trust has proved itself a busted flush.

It’s not the first time. It has been confusing for the public to see the Chair of the Trust as the key defender of the BBC – or, as happened with Chris Patten and George Entwistle, to see the Chair and the DG side by side, shoulder to shoulder even as one was preparing to dismiss the other. That doesn’t seem like regulation. However able or independently minded the Chair might be – and it is not exactly an enviable position – she will always be caught in a double bind of either undermining the Corporation or lip-syncing the Director General.

So it is time for a clear break.

Firstly, I suggest the BBC needs a proper unitary executive board, with a non-executive Chair and a majority of non-executive directors who should be appointed for a fixed period so that they retain their independence. Their focus should be not to act as a regulator of the BBC but to carry the fiduciary responsibility of the Corporation, ensuring that it is well run financially and creatively and within the law. The Chair should be appointed by the Government after nomination hearings by the Parliamentary Select Committee. It should be for the Chair and the non-executive directors to appoint the Director-General.

Second. For many years the BBC has fought off external regulation. It has argued that it is unique, a one-off – and so it is.

I do not think, however, that this means it should evade proper regulation and oversight. Parliament will of course maintain an important role representing the public – a role it has been particularly assiduous about in the last couple of years with almost weekly appearances of senior executives before one committee or other. But the BBC should now be fully subject to the National Audit Office.

This leaves the question of regulation.

The DCMS Committee argued for a particular model with this role split between Ofcom and a new Public Service Broadcasting Commission.

I see their point but I fear that within weeks of its appointment this Commission would be colonised by the BBC and would become the Governors or the Trust Mk II in all but name. That is why I would far prefer to see the full regulatory role adopted by Ofcom. I accept that some aspects of regulating the BBC would have to remain distinct from the regulation of other commercial broadcasters – not least because the BBC is not just a broadcaster.

But judgements on impartiality and the operation of electoral law apply identically. So could matters of taste and decency. Technical matters such as the operation of independent production quotas are better administered by Ofcom, which has proved itself to be a highly effective regulator. Where Ofcom has not thus far trod, in assessing the public service remit of the BBC, or in judging the merits of licence fee spend on internet services, this could readily be done by a BBC Committee within Ofcom.

Conclusion

If what has been briefed to the press is right, the Government seems to be asking all the wrong questions about the BBC. Far from ‘crowding out’ commercial operators, the BBC has taken a smaller and smaller share of the market since 1985. Then it had nearly half of all television industry income, now it has less than a quarter.

Soon it will be less than a fifth.

My fear is that on this trajectory if the Government engages in a deliberate attempt to limit the BBC in the Charter renewal, the BBC will be a national irrelevance by 2027, little more than a PBS channel. Even if the BBC gets its CPI inflation rise as half-promised, it will still be shrinking even as sports rights’, movie rights’ and top talent inflation are racing ahead. And we shall all be the poorer for it. Less British programming and fewer great British talents on our screens and winning Oscars.

The very use of the words ‘scope and scale’, which were expressly changed to purpose and scope in negotiation with the BBC, is instructive. Let’s be clear, if the Cameron/Osborne/Javid/Whittingdale aim is to cut the BBC down to size, they do not carry the nation with them in this particular bully crusade. And I will fight them every inch of the way. I hope you will do too. We have just 18 months.