Mark Lawson considers Hugh Grant's career transforming role as Jeremy Thorpe in A Very English Scandal

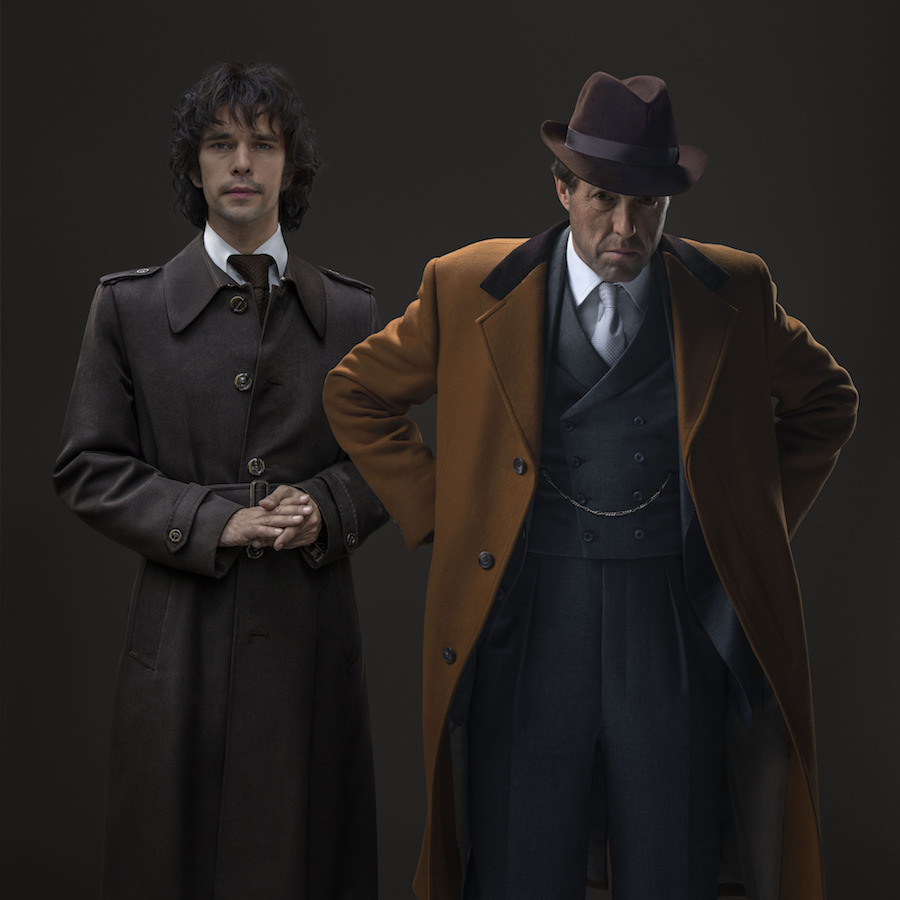

Halfway through 2018, it already seems clear who some of the leading contenders will be in the actor categories of next year’s Bafta and RTS awards: Benedict Cumberbatch and Anthony Hopkins for their title roles in Patrick Melrose and King Lear, and Ben Whishaw and Hugh Grant as Norman Scott and Jeremy Thorpe in A Very English Scandal.

Grant would be most tipsters’ pick to take home the trophies. This is a remarkable achievement. While Cumberbatch, Hopkins and Whishaw are often the names inside the gilded envelopes ripped open at TV award ceremonies, Grant’s last big British TV role, before taking on the role of the allegedly homicidal Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe in A Very English Scandal, was over 25 years ago. In 1993, he appeared in a production of Thomas Middleton’s The Changeling, in the BBC theatre-on-TV series Performance.

The reason for Grant’s quarter-century absence from the medium was his movie-star career, especially as Richard Curtis’s preferred lead man in Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill and Love Actually.

But, whereas some screen stars who take a TV role – such as Frances McDormand in Olive Kitteridge or Matthew McConaughey in True Detective – merely fancy the chance to do classy, long-form material in between Hollywood projects, Grant was widely perceived to be in trouble cinematically.

His movie work in the past decade had suggested someone now too old and cynical to lead romcoms such as Music and Lyrics (2007) and The Rewrite (2014), but still too associated with stuttering lovers to be taken seriously when playing five roles in the postmodern sci-fi mega-flop Cloud Atlas (2012). So, his performance as Thorpe is a total reputational turnaround, one of the finest ever achieved by an actor.

"The relevance of Grant’s own sexual risk-taking is that it reveals a darker streak in his personality, one that is more interesting than he has generally been allowed to appear on screen"

The transformation was achieved through a combination of reanimated talent and lookalike luck. In a screen industry ever more dominated by bio-dramas, an actor’s face and physique can suddenly become their fortune.

For example, Toby Jones is a great screen actor but would require unfeasible cosmetic and camera trickery to convince as Thorpe.

However, as soon as it was reported that Grant would play Thorpe, the casting immediately made sense. They shared not only Oxford-educated voices and the same tall, thin build (the men’s ectomorphic frames and long faces brought even closer by dieting and make-up), but psychology, too.

The events that led to Grant being charged with lewd behaviour with a sex worker on Sunset Boulevard in 1995 are now far past the statute of limitations for any effect they should have on the actor’s profession and reputation.

However, I mention the incident because there must be a suspicion that having once jeopardised his career for a sex act was a useful reference point for an actor playing Thorpe.

A Very English Scandal (Credit: BBC)

His covert encounters with men – at a time when gay sex was first illegal and then merely unpalatable to much of the electorate – resulted in allegations that, in order to protect his parliamentary career, he had conspired to have his former lover Norman Scott murdered. It was an accusation that an Old Bailey jury, firmly nudged in that direction by the judge, rejected in 1979 – but which most viewers of A Very English Scandal are likely to have concluded to be true.

The relevance of Grant’s own sexual risk-taking is that it reveals a darker streak in his personality, one that is more interesting than he has generally been allowed to appear on screen.

As is often the case, the persona that made the actor famous – the bumbling public school boy in Four Weddings and a Funeral and Notting Hill – turns out not to be the best use of his talent.

Grant is best when dark, and not even necessarily in films aimed at grown-ups.

The remarkable renaissance that A Very English Scandal represents was, in retrospect, signalled by his previous role, an enjoyable turn in Paddington 2 as Phoenix Buchanan, a vain and villainous actor.

As Grant’s cinematic part before that was St Clair Bayfield, a failed Shakespearean actor, in Florence Foster Jenkins, there was reason to fear that his screen career may have been dwindling to knowing, self-parodic cameos.

"The greatness of the portrayal is the transmission of the calculations and contradictions happening inside Thorpe’s head"

But these usefully highlighted a different side of his style, which Stephen Frears, the director of Florence Foster Jenkins as well as A Very English Scandal, utilised fully as Thorpe, another strange theatrical of sorts, though one minus an Equity card. One of Thorpe’s former lovers described him, in Michael Bloch’s 2014 biography, as a “ham actor”. This suggests that Grant’s rediscovery as a good actor has now, paradoxically, featured a trio of bad ones.

The biggest tribute to Grant’s performance in A Very English Scandal is that the obligatory coda, in which news footage of the real figure is shown, does not have the usual deflationary effect.

The actor perfectly reproduces every vocal and physical tic, down to the wave – and what follows it. Both arms are raised and then suddenly crossed. This was a gesture Thorpe curiously shared with another disgraced leader of the 1970s, President Richard Nixon.

For an actor, that is just “living Tussaud’s” stuff. The greatness of the portrayal is the transmission of the calculations and contradictions happening inside Thorpe’s head.

Russell T Davies’s scripts for A Very English Scandal often sought to position the protagonist as a victim of historical discrimination against homosexuals, forced into two “lavender marriages”. Expression of his true sexuality would have wrecked his high political ambitions.

Davies gives Thorpe a line about how he will consummate his marriages “through gritted teeth” and subsequently plead tiredness at bedtime.

This is a reasonable reading, especially from the writer of Queer as Folk, but biographies and contemporary reports of Thorpe’s life suggest the alternative possibility that he was an enthusiastic bisexual, who enjoyed the risk created by satisfying both sides of his libido.

And the suggestion in Bloch’s biography that Thorpe may have ordered the murder of another man who knew too much – a former lover, Henry Upton, who mysteriously disappeared at sea in 1957 – raises the possibility that he was psychotic. Grant convincingly suggests a man who would have been capable of almost anything in pursuit of his sexual desires and political ambitions.

A late-career role that fits an actor exactly can sometimes be an opening that closes off options: Nigel Hawthorne and F Murray Abraham were often hard to cast after the perfection of their work as Sir Humphrey in Yes Minister and Salieri in Amadeus.

It seems different in Grant’s case, though, because this is a second breakthrough and represents an escape from earlier typecasting. He surely couldn’t go back to playing the posh love interest in Richard Curtis films, but most would see that as a good thing. If that interesting quintet of performances in Cloud Atlas were premiered now, it would, perhaps, be better received.

A well-known screen director, who declines to be named for making a negative comparison with another actor, says: “Watching Grant in A Very English Scandal, I kept imagining him in the part played by Hugh Laurie in The Night Manager. I think he’d have been much more convincing as that satanic figure.

“Grant wouldn’t have been thought of for that part two years ago, but now he would be. So, the big change will be in the range of what he can do.”

Before that, he should ensure he has a clean tuxedo for the TV awards season.