For virtually its entire existence, the vast global television industry has survived and thrived amid a series of transformations. Here’s how it can surf the next wave.

Call it a tale of two industries. For the vast global television sector, this is the best of times and the worst of times. This is a golden age of television.

Cinema-quality programmes such as Game of Thrones draw massive audiences. Events such as the 2018 FIFA World Cup, broadcast in real time to a global viewership of 1.1 billion, prove the medium’s unique power to bring together truly massive live audiences.

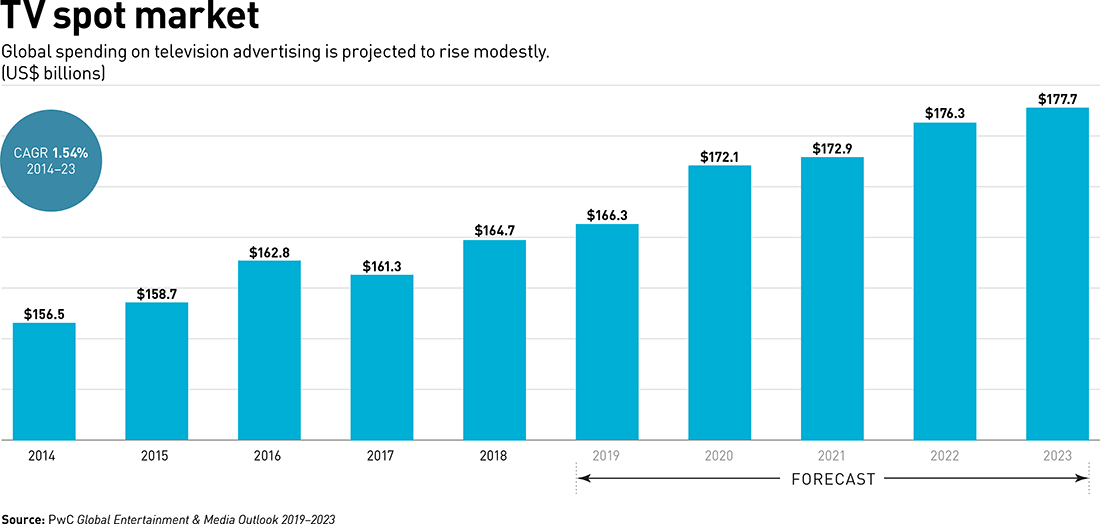

People are watching more television than ever, and advertising revenues continue to grow. According to the PwC Global Entertainment & Media Outlook, global television advertising rose 2 percent in 2018 off a very large base (US$164 billion), and will rise at a 1.5 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) through 2023.

There is a global arms race surrounding original programming. To keep up with Amazon and Netflix, which is expected to spend $15 billion on content in 2019, Sky announced that it would double its annual investment in original shows to £1 billion (US$1.2 billion) per year as part of its drive to become the “leading force in European content development and production.”

And yet the airwaves, thought leadership channels, and industry conferences are filled with apocalyptic predictions.

They say that millennials by the millions are cutting the cord and Generation Z will likely be a large cohort of “never corders,” armed with log-ins for Netflix, Amazon Prime, and YouTube Premium.

They say that linear television is dying, a victim of technology and changing consumer habits.

They say that as marketers demand targeted advertising that can be measured more accurately, the 30-second spot — for decades the lifeblood of the TV ad business — will wither away.

They say that the launch of 5G will give consumers mobile services that are delivered 100 times faster with 1,000 times more capacity than those from 4G, paving the way for truly interactive television.

The truth, of course, lies somewhere in between these two extremes. Shifts in viewer behaviour are often less dramatic and organisations more resilient to change than dire forecasts would have us think.

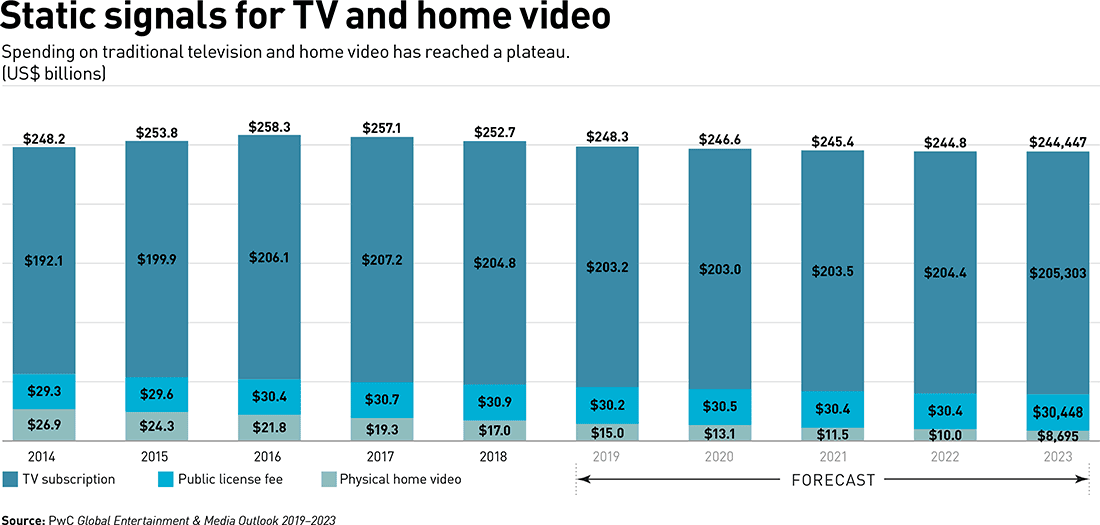

According to the Outlook, total global consumer spending on traditional television and home video has fallen for the past two years, and will decline for each of the next five — at a modest 0.66 percent CAGR (see “TV spot market”). Some of these powerful shifts play into the hands of incumbents, and many of the seeming threats are opportunities.

For example, 5G will allow consumers to watch television content easily on mobile devices without the need for a Wi-Fi connection, and will improve the effectiveness and efficiency of live broadcasts.

More broadly, as much as people characterise them as challenged and fusty operations, television organisations have a very long history of operating in hybrid environments in the midst of structural shifts: from film and radio to broadcast television in the 1940s and 1950s, from black-and-white to colour in the 1960s, from broadcast to cable and satellite in the 1970s and 1980s, from analog to digital in the 1990s, and then from SD to HD, from broadcast/cable/satellite to streaming in the 2000s, and from HD to 4K in this decade and 8K and ATSC 3.0 in the next.

This industry has surfed technological and cultural waves successfully in the past. There’s no reason it can’t do so in the future. Embracing what’s to come across all areas of operations is the strategic imperative for major national television networks and production companies — and is the subject of this article.

Jonathan Thompson, CEO of Digital UK, told us: “National TV networks need to radically reconsider their breadth of content, relationships with audiences, and partnerships.”

In the face of challenges and disruptive forces, incumbents aren’t sitting idly by. They are actively considering where and how they should be playing. There has been significant consolidation between content players (e.g., the 2018 $14 billion acquisition of Scripps Networks by Discovery Communications and Disney’s 2019 $71 billion acquisition of 21st Century Fox) and content and distribution (AT&T’s 2018 $85 billion acquisition of Time Warner and Comcast’s 2018 $39 billion acquisition of Sky).

Such moves can generate substantial cost synergies (AT&T promised $2.5 billion in synergy savings over the first three years), as well as benefits from deploying intellectual property (IP) such as proprietary advertising or content across a larger footprint and direct-to-consumer channels. AT&T’s Warner Media streaming service will now include content powerhouses such as HBO, CNN, and Turner channels, for example.

Others have undertaken aggressive cost reduction exercises, ranging from organisational simplification to the disposal of non-core assets. Disney/ABC Television focused on reducing roles in non-content-related or operational areas, whereas Liberty Global decentralized and rationalized its organisation after it sold some of its assets to Vodafone.

Smaller players are doubling down on their differentiated products. “The point is that in any market there will always be room for distinctive propositions from smaller players with a clarity of consumer focus and brand identity,” said Keith Underwood, chief operating officer of Channel 4.

Besides the proliferation of their own services, incumbents are also looking to partnerships to drive increased reach and minimise defections from their platform. Pay-TV platforms have been striking deals with over-the-top (OTT) platforms. In the U.K., the BBC and ITV are establishing a joint venture, BritBox, which offers a broad range of streaming British television content to viewers on a subscription basis.

In Australia, free-to-air commercial and national broadcasters joined together to offer a live streaming and BVOD (broadcast video on demand) TV service, Freeview, in 2016. Some players are seeking policy support to maintain due prominence on electric program guides and working to harmonise regulation in the on-demand and broadcast worlds.

All these steps, though sensible and necessary, are not sufficient. These essentially defensive moves won’t be enough to enable incumbents to maintain their position, let alone grow profitably.

That’s because, as the futurist Roy Amara famously noted, “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

There are limits to the impact of refining an existing model. In fact, based on our extensive research and advisory experience, and having conducted frank and in-depth discussions with 20 executives at television companies and investors on this topic, we believe that a fundamental reinvention will be necessary to assure survival and growth.

These efforts should be aimed at building a television organisation within an ecosystem of strategies that we call Fit for Growth*, one that can pursue an approach to transformation that connects choices about purpose, capability development, cost management, and organisational and cultural evolution.

The reinvention imperative

Success will be a result not of reengineering the TV business but of re-imagining it. This reinvention requires incumbents to adopt the mind-set of a startup, using “zero-based” design.

The process begins with asking a series of probing questions about your organisation: If you were to set up your studio, network, or production company from scratch, what would it look like? How would you delight the customers you most want to serve? How can you best compete creatively? How much of your existing portfolio should be transitioned, restructured, or exited based on the strengths you start with?

Posing and answering these strategic questions, and then creating a digital twin, or prototype, for the organisation will enable leaders to test new practices.

Focus on the customer. The first necessary strategic step is for television companies to evolve and intensify a customer-first mind-set. It seems obvious, but many of the biggest broadcasters or production companies grew and prospered without thinking all that much about the end customers’ needs or desires — beyond the content they served.

Today, technology, platforms, and behaviour put consumers in control of TV in an entirely new way — whether that is through installing ad-blocking software, cutting the cord, downloading, streaming, buying, sharing, personalising, or commenting on content in real time on social media.

Not surprisingly, the rise of OTT subscription video on demand (SVOD) players, which afford consumers immense control, was the issue preoccupying the executives we interviewed. They are simultaneously, in the words of our interviewees, “throwing the traditional model on its head” and “forcing quicker strategic moves by traditional players.”

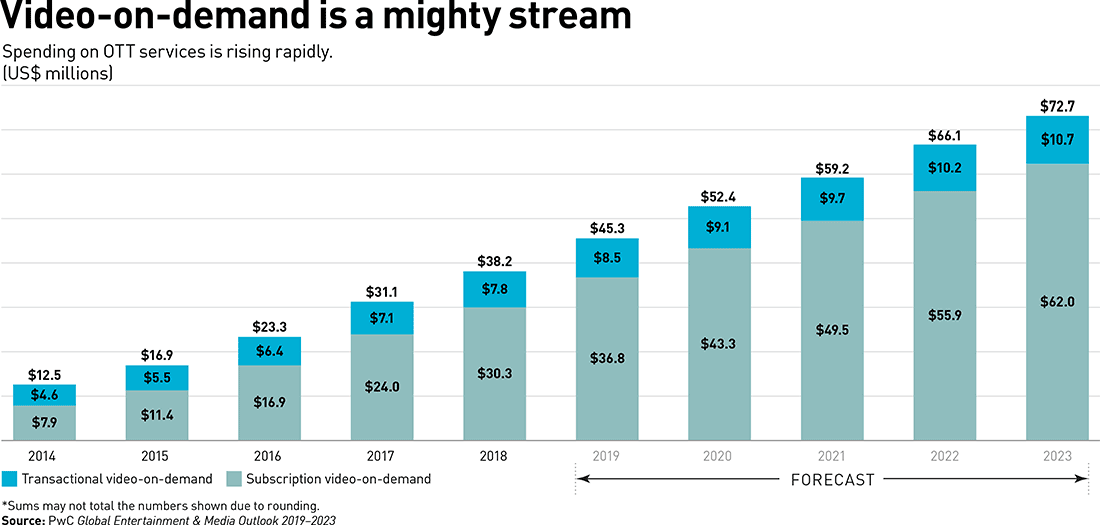

According to the Outlook, OTT revenue more than tripled between 2014 and 2018, from $12.5 billion to $38.2 billion, and is projected to nearly double by 2023 to $72.7 billion, even as revenues for traditional TV subscriptions and advertising essentially stagnate (see “Video-on-demand is a mighty stream”).

SVODs have features that characterise successful consumer-first businesses and industries. They use sophisticated audience analytics to develop more personalised content and recommendations, refine the customer experience to make it easier to discover content and stay longer on the service, and offer new forms of packaging (e.g., the advent of boxed sets designed to promote binge-viewing) and innovative payment models for content that encourage bigger risk taking.

In some instances, thanks to their consumer focus, these companies have a fundamentally different view of success. For example, is content the core business, or is it a catalyst for other revenue streams?

Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, said, “When we win a Golden Globe, it helps us sell more shoes.” In Australia, News Corp has a venture arm that invests in consumer-facing businesses that can scale by tapping into the company’s advertising inventory.

Of course, SVOD players face their own challenges. Television companies must begin to adopt some of the tactics and the mind-set of consumer-oriented SVOD players. Some already are doing so. “We will always be willing to adapt our business model to fit the needs of the consumer rather than expect [the consumer] to adapt to meet the needs of our business,” said Jeremy Darroch, CEO of Sky.

New players, new challenges

As impressive as the growth has been of alternatives to television including OTT and SVOD providers, they face their own strategic challenges — how to drive greater profitability, maintain their license to operate, and improve their consumer experience. Our research shows that many users are dissatisfied with the experience and recommendations offered up to them.

Consumers value services that are frictionless and have an exhaustive content library even more than they do services that offer discounts on monthly cost or free trials; 33 percent of consumers we surveyed said that they picked their preferred SVOD service for its ease of use (the top answer), but in earlier research, only 12 percent said that their favourite shows were easily accessible. Consumers need a user interface that helps and guides them through an enjoyable experience, be it finding new content or making it easier for them to enjoy their favourite shows. And they have a desire for expanded browsing options, such as being able to search by mood or by length of content. There’s certainly potential for greater integration of TV content and interactive games.

Some SVODs are using the best features of the incumbents they’re seeking to displace. They’re investing in appointment-to-view content, creating channels, and developing production hubs in the United States, continental Europe, and the United Kingdom. Much as cable television operators have been doing since the 1980s, SVOD players are rolling out services catering to specialist genres or audiences — Crunchyroll for Asian TV, Fandor for independent movies, and Disney+ for children and young people. The obvious concerns in the industry are how quickly there will be an over-saturation of SVOD platforms and whether customers who were accustomed to receiving access to dozens or hundreds of channels through a single cable or satellite television will start to feel subscription fatigue as they are asked to sign up and pay for an expanding array of options.

Refresh the leadership team. Adopting a customer-first mind-set is just one dimension of how leadership’s perspective needs to change if a television company is to develop new strategies. Historically, leaders have focused on a discrete and linear set of activities: Commission and acquire content, distribute content, and sell advertising and subscriptions — generally on a regional or national basis.

In the new world, the range of activities and relationships they’re responsible for has expanded. Leadership teams need to build a more global, open perspective, while building on the strengths that often reside in national linear television markets.

The management of portfolios — of content, products, services, communities of fans, and technologies — becomes a differentiating capability that can help the C-suite maximise the return on investment. Leaders must have a clear plan for cannibalization as a way to self-disrupt and clear standards for responsible use of content, brands, algorithms, and data, as well as for responsible interaction with their audiences (especially vis-à-vis the perils of addiction). In this scheme, the HQ, or central office, has to evolve from the seat of an empire that issues commands into an enabler, a catalyst for new investments and beacon for partners and suppliers in an ecosystem.

Leaders must model empowering, innovative, and ethical behaviours; instill a mind-set of continual renewal; create the conditions for psychological safety; and make bold, transparent decisions as to where to focus. In most cases, this will require adding fresh faces and voices, both to help the team upskill and to challenge prevailing ways of thinking and doing. Some of the most significant success stories over the past decade have resulted from inspirational leaders marrying an innovative mind-set with commercial acumen and a positive attitude.

Take an honest view of the business. An important component of leadership is to consciously and aggressively question — and allow for the questioning of — existing practices. When leaders or middle managers use the phrase “That’s the way we do things around here,” Freek Vermeulen of London Business School notes, “It’s an instant clue that you’ve found a bad habit that needs to stop.”

The reinvention exercise should tackle the inefficiencies and frictions that plague many incumbent TV organisations. Most of the technology, systems, workflows, business practices, and behaviours were created in an environment that was domestic, linear, and non-digital, and in which audiences were generally passive and perceived to be homogeneous.

But most organisations are now operating in an international, if not global, landscape, and distribution is almost entirely digital. One interviewee noted that the television production value chain was “archaic due to industry structure...and incumbents who haven’t modernized.”

The challenge cascades through the organisation, from the beginning of the process to the end. One interviewee noted that “commissioners or creatives that are too pleased with themselves” impede creative and commercial breakthroughs. The slow pace of deal making doesn’t help either; spending a year commissioning a drama series is no longer a viable plan. And continuing to present content primarily through brands — for example, in the design of the user interface — creates confusion with consumers who want to find their favourite program more easily.

Companies, advertisers, and investors have difficulty getting a clear view of the return on the investments they make because there is a lack of rigorous, reliable cross-platform measurement and reporting of audiences, and often ineffective tracking of content rights (what they own, where, and on what platform). And commercial arrangements frequently don’t reflect the value of the content or IP; examples include having too many cost-plus arrangements or contractual terms that have not kept pace with the technology platforms through which the content flows.

Learn to become more agile. One interviewee said that the arrival of SVOD businesses had heralded a shift in mind-set: “SVODs see the value of progress through innovation and change rather than the value of loss and gain (rights ownership based on a fully finished product).

The existing TV industry looks straight ahead — commission, execute, sell; the new players are more entrepreneurial, looking upward and further ahead.” Indeed, given the rising importance of technology and the high expectations of consumers, television companies have to become more agile, acting more like direct-to-consumer businesses.

They must be agile in moving financial, human, behavioural, and cognitive capital to the places where it can produce the highest payback.

They must know what is good enough in order to make progress, striking a balance between rigour and speed. They must be agile (and empathetic) in responding to the needs and expectations of audiences, who consistently ask for more simplicity in design.

As Lucinda Hicks, COO of Endemol Shine UK, said, “What can scale give you in the TV production business? Strength, diversification, resilience. But you need to be mindful to keep things simple and flexible.” And companies must explore new opportunities courageously, as BBC Studios has done with One Cup, its first fully funded commission in China for Migu, China Mobile’s digital content subsidiary, which tells the story of the impact of tea.

Build innovative creative factories. As they compete for a scarcity of creative professionals, especially writers, it is vital that television companies function as innovative, creative content factories. Just as the most progressive content and software companies do, these should have a startup feel, and combine the best of creativity with data analytics in pop-up environments.

They should be designed in a modular fashion so they don’t saddle the company with large fixed costs.

They can deploy the strongest elements of agile development in software, games, and music, with more distributed responsibility, autonomous working, and transparency of information and decisions, as is practised at Spotify and Google.

Professionals in modern working environments will employ flexible resourcing (using talent platforms such as Crewfund.co) and cloud-based technology infrastructure to produce, manage, and distribute content efficiently and securely. The results will be a substantially lower cost base, faster speed-to-market, and a more engaged workforce, within and outside the organisation.

Develop a strategic ecosystem. Just as television companies must focus on building innovative internal ecosystems, they must also be conscious of — and able to nurture — larger external ecosystems.

The rise of SVOD operations has been pivotal in shifting the TV industry towards an ecosystem defined by Michael Jacobides of London Business School as “fluid networks of organisations combining to deliver bundles of products and services in new and unfamiliar ways.” The ability to nurture an ecosystem that includes a significant number of organisations, in several countries, and that features a variety of functional skills will become a differentiating capability.

The slow pace of deal making doesn’t help; spending a year commissioning a drama series is no longer a viable plan.

Many incumbents have grown up as the dominant player in their industry, able to call the shots with a fixed number of content and technology suppliers. As their power is waning, the range of possible organisations they can work with is increasing rapidly — there are legions of new distributors, technology developers, analytics providers, and e-commerce and advertising partners.

At the same time, some of television’s former customers (namely, the OTT players) are functioning as competitors for talent, content, and audiences. These developments require incumbents to develop new skills, vocabulary, and approaches surrounding partnering.

There are new pathways for the discovery and consumption of television. Gaming and social platforms, such as Twitch, are the default home for individuals who then watch TV in some form rather than starting with a traditional TV platform, channel, or service.

In developing markets, apps developed for ride-hailing or e-commerce are adding streaming video content, as Bukalapak, an Indonesian e-commerce platform, does. And 21st Century Fox signalled its interest in new pathways by creating a joint venture with a social live-streaming startup called Caffeine Studios to produce exclusive e-sports, video game, sports, and live entertainment content.

Given the changing landscape, leaders must figure out who they need to be working with — and in what capacity — and how they can encourage new entrants to work with them. This will require a mind-set of curiosity, openness to experimenting with new approaches (as the short-form content company Quibi is doing with the way content rights are funded and owned), and a flexibility in ways of working.

Companies will have to become comfortable working with other organisations, including direct competitors, so they can satisfy customer expectations and compete against the scale of the OTT players.

Give technologists their due. Emerging technologies, such as AI and blockchain, have the potential to transform the way content is developed, distributed, and monetized. In the UK, Channel 4 tested the use of AI to identify scenes in programmes that it could pair with contextual advertisements.

Spott, a startup based in Belgium, uses AI to drive interactive, transactional revenues by recognising and tracking objects in video advertisements, so consumers can click on an ad and buy an item directly. The production company Endemol Shine has adopted a cloud-based workflow solution that applies machine learning to the indexing of video files using text, facial recognition, and related technology, saving hours of manual data entry and review.

Blockchain has the potential to help fund and monetize television content as well as to help manage it by enabling more effective tracking of rights and more direct relationships between content owners, advertisers, and consumers; at present, content is self-reported by the companies airing programming, which results in errors and causes friction between stakeholders.

Comcast is partnering with Charter and Viacom in a project called Blockgraph to create a blockchain-enabled exchange for addressable advertising data. Breaker, a social podcast app, relies on a tokenized ecosystem using a cryptocurrency called SNGLS to help artists and creators benefit from transparent media production and distribution.

The addressable future

Because it delivers more personalised experiences for audiences watching the same program, addressable advertising (which can serve different ads to viewers of the same show) offers the benefits of more precision and greater efficiency. The opinions of our interviewees on addressable advertising were mixed. Some could see the potential, while others were more cautious, with one describing it as a “Pandora’s box. We have no idea what will happen if you use analytics in spot advertising, and people are scared of opening the box.”

Rich Astley, chief product officer of Finecast, one of the early pioneers in this area (having launched in 2017), is more bullish: “Addressable TV advertising offers a potentially significant yield improvement through a significantly higher cost per thousand through the application of data and technology and by reducing the cost of entry to TV from other sectors of marketing investment (e.g., local, retail, or direct response media).”

According to marketing research organisation WARC, addressable TV advertising continues to see rapid growth — it has reached US$1 billion worldwide in 2019 — and now represents a 0.7 percent share of the total linear TV advertising market. WARC predicts that by 2022, addressable advertising’s share will be 10 percent. New partnerships between erstwhile competitors are emerging. In the UK, Virgin Media will use both Sky’s AdSmart and the tech developed by its parent company Liberty Global.

U.K.-based Covatic is an early-stage example of using mobile-based algorithms to bring smart personalisation to apps, which enables more effective targeted advertising. Networks are also developing innovative solutions directly for advertisers. In early 2019, Channel 4 launched Dynamic TV, a tool that enables advertisers to run their own custom audience segments across Channel 4’s platforms with direct calls to action — allowing, for example, Boots to direct viewers to its nearest pharmacy.

Harnessing the potential of these technologies will require a significant shift in understanding and attitude on the part of leaders in the television industry (and a willingness to tackle and transition their legacy technologies). In our interviews, we observed a palpable lack of knowledge of or even interest in blockchain, and a view that there are simpler alternatives to providing universal, independent, and secure content rights.

The ability to tap into these solutions will depend on how open television organisations are to collaborating in an ecosystem environment.

Most significantly, however, technologists, who are often regarded as service providers in these organisations, must be given a more prominent role in making investment and strategic decisions. Technology needs to be viewed more as a strategic investment and differentiating capability than as an operational cost to be minimised.

New competitive arenas

Pursuing the strategies outlined above will enable TV companies to compete more effectively in their existing markets and grow more resilient to change. The thirst for high-quality, original content will present further opportunities for those companies that can produce and monetize at scale.

Just as important, the transformation will position them to play and compete in some of the new spaces we see emerging in the TV ecosystem. As consumers gain more control, technology expands and becomes more powerful, and ecosystems continue to morph and evolve, new business arrangements will present themselves. Some examples follow.

Super-aggregator of content. The fragmentation of content streams, the proliferation of platforms, and the belief among some content providers that their brand is the primary means of discovery may pave the way for an “orchestrator” of the television ecosystem to act as a curator of content.

Consumers will demand a simplicity of experience across multiple SVOD, OTT, and television offerings, as well as their social media and gaming platforms, making it easier for them to find what they want to watch. Our own research shows that 83 percent of U.S. viewers watch something new every month, but 62 percent struggle to find something to watch. Users will also want to be able to transact more easily where they’re interested in a product or service.

But the players won’t want to share their data or the user experience. Could there be space for a new player to aggregate the content and metadata that enables a more seamless and convenient user experience? “A great super-aggregation service requires not just aggregation of metadata but also…its unification to deliver a program-led discovery experience, rather than a provider brand-led experience,” said Susie Buckridge, CEO of YouView.

Service providers. Television companies can deploy their proprietary solutions on audience measurement (as well as industry-led solutions such as Project Dovetail, which focus on total reach and commercial audiences of a program across all devices), addressable advertising, rights management, or content production across their larger, consolidated groups — and with smaller third parties.

Olivier Philippe, vice president of enterprise architecture at Liberty Global, told us: “If you had a blank sheet of paper, there’s an opportunity to provide an end-to-end platform from content acquisition to distribution — the value of that IP would have to be higher than the cost of integration."

As part of their post-deal integration, Comcast and Sky have applied Comcast’s voice interface to the Sky Q line of products, offered Comcast’s xFi home Wi-Fi product to broadband customers, and adapted Sky’s OTT technology platform for Comcast customers. Some television organisations will establish units to drive this expansion with more clarity and capital. Or they may invest in business incubators that finance, manage, and scale up content globally, such as Greenbird TV.

Global AVOD player. Building on the impact of such organisations as Pluto TV, a Viacom-owned property that offers more than 100 free channels, new entrants could employ an ad-supported model that would be free to customers and utilise targeted and addressable advertising technology to drive revenues. But our research shows that consumers expect few if any ads, which means those who pursue this strategy will have to tread carefully.

Short-form content. In 2018, Quibi (short for quick bites), a startup created by Hollywood veteran Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman, the former CEO of HP and eBay, raised $1 billion in capital from investors including Alibaba Group, Walt Disney, 21st Century Fox, and Time Warner. It plans to roll out in April 2020.

Quibi is aimed at 25- to 35-year-olds on a mobile platform, and has already signed up NBC to create short-form daily news shows; it plans to transform the way people watch content and give filmmakers the opportunity to create content for mobile devices. Recognising consumers’ appetite for small bites of content, non-TV players might enter this market too.

Black Sheep, nominated for an Oscar for best short documentary, was commissioned by the Guardian. This format also affords new approaches to audience participation and commercial deals. For example, Fiction Riot, a Los Angeles–based startup launched in late 2018, offers series of three-minute to 12-minute episodes distributed on mobile technology, with 360-degree viewing, augmented reality, chat, and live streaming.

Royalties for shows viewed on its app, Ficto, are paid automatically based on the number of views, with revenue split 50/50. The company promises a $1 million payout to the first creator with an episode that reaches 1 million unique views on the app.

Self-belief

Some fascinating shifts and trends are shaping the television ecosystem. The good news for incumbents is that regardless of how TV is watched or delivered, the fundamentals persist: the pivotal role of creative genius in developing ideas, scripts, formats, and storylines; the use of vertical and horizontal integration to generate economies of scale and diversification; the power of shared, memorable event television; the importance of platforms and channels that help people find their favourite shows and talent easily; and the strength and scale of national television.

But having succeeded in the TV industry is no guarantee of future success. As we’ve noted, thriving in the emerging environment will require a shift in mind-set on the part of leaders. They’ll need to be comfortable managing amid a number of paradoxes — to be prudent and take risks, to be creative yet led by data, to move quickly but also in a reflective manner, to be open to competitors and collaborators and yet focused intently on internal operations.

In the end, though, it requires a belief in leadership that talent can be developed through hard work, strong strategies, and support from others. This belief must start at the top. Leaders must have the humility to start afresh and a hunger to do better. They must make people feel psychologically safe as they try new things or at least call out what needs to change.

They must consciously build a diversity of perspectives that help to stimulate fresh ideas and avoid groupthink. They must emphasise purpose, encourage participation, destigmatise failure, and express appreciation. Above all, they must recognise that when something isn’t working, it’s better to change the channel.

Reprinted with permission from "Transforming TV by going back to the future" from strategy+business. © 2019 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. www.strategy-business.com