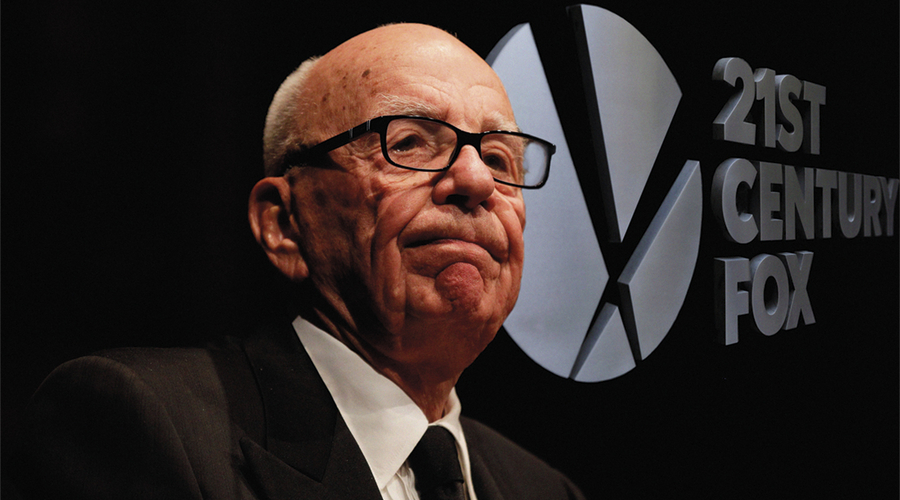

As Comcast and Disney vie to buy the Murdoch entertainment empire, Mathew Horsman assesses the likely outcomes

However it ends, the battle royal for the right to own most of the assets of 21st Century Fox, and all of Sky, reflects deep and significant trends in global media. The resolution (in favour of suitors Disney, Comcast or both) may end up being less important than what the outcome tells us about market dynamics.

This battle is about the response of legacy media to accelerating shifts in consumer behaviour and to the threats posed by the big digital disruptors. In a market where content and distribution are increasingly intermingled and global, size unlocks the prize.

For those who haven’t been following, here is the recap: Fox, a range of mostly traditional media assets, owned in part by the Murdoch Family Trust, agreed to sell key components (film and TV production, pay-TV channels, Star India and 39% of pay-TV operator Sky) to content giant Disney in December last year for $52bn in Disney shares.

That agreed deal followed the latest (and separate) bid by Fox to buy the shares in Sky it doesn’t already own for £10.75 a share (£19bn), which remained mired in regulatory molasses for months thereafter.

The idea was for Fox to buy all of Sky, and then sell those assets and the other Fox film, TV and channels operations to Disney. The Murdochs would end up with a small but valuable stake in the enlarged Disney.

Upsetting that narrative, US cable and broadband operator Comcast took advantage of the long, drawn-out regulatory process around ownership of Sky. The concerns are around media plurality in respect of Murdoch’s ownership of UK newspapers and indirect ownership of Sky News.

Comcast’s bid valued Sky at £12.50 a share (£22bn), with the clear aim of wrong-footing Disney.

Not content with the spoiler move on Sky, Comcast followed up with a premium bid for Fox ($65bn in cash), saying that it wanted the same assets that Disney had agreed to buy.

Disney then raised its bid for Fox to well above Comcast’s offer ($71bn). This time, it offered cash or shares and again secured the support of the Fox board; Murdoch, for tax reasons, prefers shares to cash. In late June, Disney’s bid was cleared by the US Department of Justice.

On this side of the Atlantic, Fox’s bid for Sky is in the process of winning final approval, following an agreement with the Government that Fox will ensure Sky News is owned by Disney directly in the event that Fox succeeds in buying the rest of Sky. Comcast’s bid for Sky has already been waved through by regulators. Now shareholders have to decide.

"Personalities aside, the main issue here is global scale – for content and distribution"

At the time of writing, the markets were awaiting Comcast’s comeback on Fox and Disney’s latest response on Sky.

There are delightful personality clashes at work here that make the story even better. Bob Iger, Disney’s Chief Executive, has crossed swords several times with Comcast’s Brian Roberts and his senior TV executive Steve Burke. Indeed, Comcast tried in vain in 2004 to buy Disney, criticising the company’s TV network performance. At the time, Disney-owned ABC was chaired by Iger. Comcast went on to buy NBCUniversal instead.

Comcast also approached Fox in 2017, eager to pre-empt any tie-up between Disney and Fox. Its offer was deemed to be too difficult to achieve from a regulatory perspective, even if it was willing to bid more than Disney.

means that Disney will own Sky News directly (Credit: Sky)

The decision, a few weeks ago, by a US court to allow the acquisition of Time Warner by AT&T signalled that vertical mergers might be acceptable after all, and emboldened Comcast to re-enter the fray.

Personalities aside, the main issue here is global scale – for content and distribution. The business models for network and pay-TV alike have been seriously disrupted by the emergence and fast growth of challengers such as Netflix and Amazon. These services are now in tens of millions of households worldwide. They are spending freely on original and acquired content in competition with broadcasters and pay-TV operators.

Google is building its long-form video presence and Facebook and Apple are dipping their toes into content waters. The old model – big bundles of pay-TV offered at ever higher prices to consumers and mass-market TV shows funded by advertising – is in decline. In its place: lower-priced access to content where and when consumers want it.

The response of companies with legacy assets (studios, cable and satellite networks, TV channels) is to sell out (Murdoch) or to double down (Disney, Comcast). Being in between simply doesn’t work. That Rupert Murdoch is a seller not a buyer of media assets speaks volumes about the extent of the challenges. His judgement is that it is time to cash in his chips.

For its part, Disney has already placed multiple bets on content, buying Pixar (animation), Lucasfilm (Star Wars) and Marvel (superheroes) to add to its already big studio operations.

It now wants to fold in Fox’s studio assets (such as X-Men and Avatar), together with an array of pay-TV channels. The local TV licences, regional sports networks and local sports channels stay with Fox shareholders.

Disney will then take the next, confrontational step toward no-holds-barred combat with the new entrants: removing its content from Netflix and competing toe to toe in the direct-to-consumer market by offering its own, enhanced SVoD proposition.

Comcast, owner of NBCU, also subscribes to the notion that scale in content ownership is crucial. It wants those same Fox assets for itself. It also appears to covet the international assets that come with Fox: Star India and the 39% stake in Sky. The latter operates in the UK, Ireland, Austria, Germany and Italy and owns the over-the-top challenger brand Now TV.

"In all scenarios, Murdoch père cashes in on a lifetime’s work"

Both Disney and Comcast will be mindful of another prize – control of the third-largest US SVoD service, Hulu. Fox, Disney and Comcast each have 30% stakes in the service, while Time Warner’s HBO has 10%. Propositions such as Netflix and Hulu are growing, while pay-TV subscriptions (Comcast’s core business) are not.

It is an irony that a bidding war for a range of assets thought by many to be in decline, or at the very least severely challenged, has erupted just as Netflix, the poster boy of new media models, saw its market capitalisation exceed that of Disney. Is the market not overvaluing yesterday’s winners at tomorrow’s prices?

It is a safe bet that, over the course of the summer, a victor for Fox will be declared, perhaps as early as July. Neither Comcast nor Disney wants to lose. But Comcast has the bigger challenge of staying the course financially: its balance sheet carries more debt and its share price is trading significantly below the levels of early 2018. This is one of the reasons that its bid for Fox is in cash. Moreover, given its head start, Disney is ahead on the regulatory timetable in the US.

There are many potential sidetracks, deviations and wrong turns. But there are three likely outcomes.

Disney wins both Fox and Sky. Comcast does so. Or, perhaps less likely given the high stakes, there is a split decision, with Disney taking the Fox assets and Comcast winning the battle for Sky.

In all scenarios, Murdoch père cashes in on a lifetime’s work.

In any event, very little will change from a UK perspective. One big US-based shareholder will be replaced by another (with all the implications of global content and distribution trends inescapably present). The only big difference: no Murdoch at Sky for the first time in its history.

Losing out on Fox will be a bitter blow for one of the two parties. The impact might be softened by the knowledge, perhaps, that the winner paid too much.

Mathew Horsman is director of the consultancy Mediatique.