Across Europe public service TV faces multiple challenges, explains Claire Enders.

There is a sea change afoot across European public service broadcasting (PSB). Alongside the ongoing tumult that surrounds the future of the BBC and Channel 4, several continental European PSBs have recently undergone significant reforms to their funding models. All this comes at a time when they face an intensifying battle for eyeballs and production resources with predominantly US-based streaming giants.

There is significant variation in the market conditions, public perceptions and financial health of PSBs, but there is commonality in terms of the audience and revenue challenges they face. Across the countries of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), between 2015 and 2020, the total weekly reach of the PSBs dropped by 5 percentage points to 61%; for 15-24s, it dropped by 10 points to only 35%.

A worrying aspect of some of these reforms is that they contribute to the erosion of impartial news and current affairs, provision of which has enabled electors to be informed and make their choices at the polls independently. Hungary is an outstanding example of how the decline of this vital institutional foundation can undermine a well-functioning democracy.

Between 2009 and 2022, 11 EBU territories dropped the licence fee. This leaves 24 out of 56 EBU countries using a licence fee to fund at least part of their PSB systems, with many methods employed for collecting the fee. The most widespread is via electricity suppliers (12 countries) and the PSBs themselves (seven countries). Other methods include using the tax authorities (France and Israel), postal services (the Irish Republic), and private companies (Switzerland and the UK).

The future of the licence-fee model is at stake in many territories, including France; the UK will launch a review of alternative funding models for the BBC in July. Ireland is also potentially in line to follow suit later this decade.

The three main reform options we have seen play out in the market are: changing the fee into a household charge (Germany); replacing it with a special, ringfenced fund outside the state budget financed by a hypothecated PSB tax (Finland and Sweden); or replacing it with direct funding from the state budget (North Macedonia, Norway and Romania).

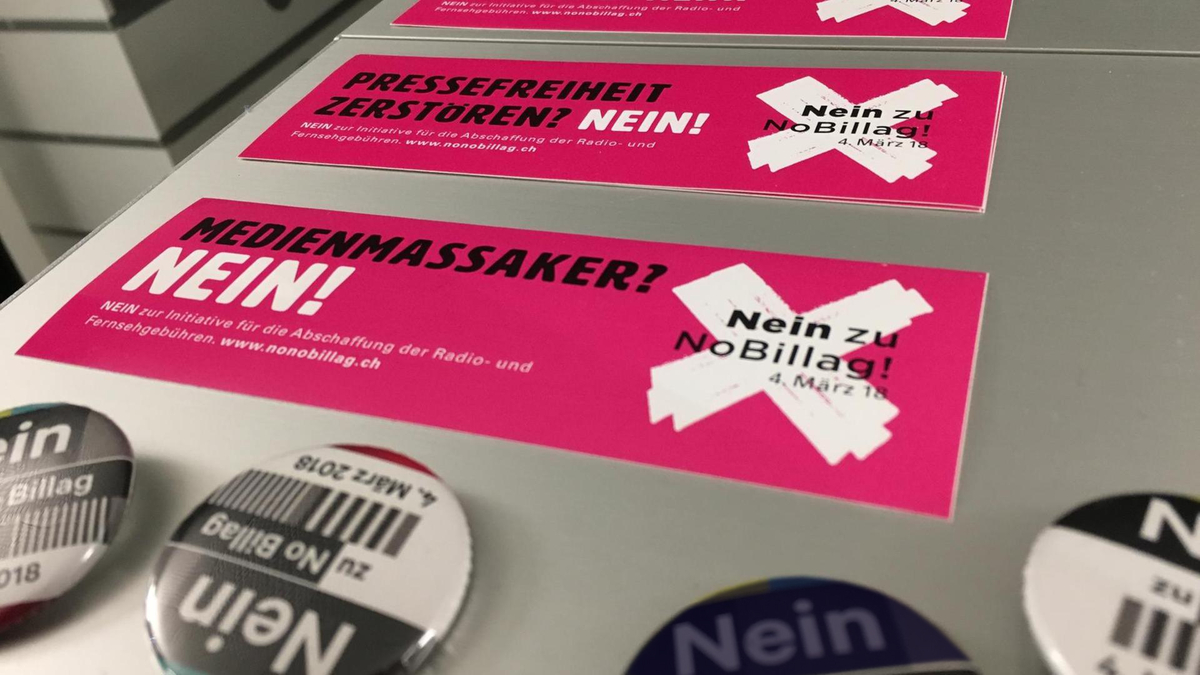

broadcaster in a vote in 2018 on whether to defund it

(credit: Dietrich Karl Mäurer)

One important outlier is Switzerland: the “No Billag” referendum in 2018 proposed the abolition of direct and indirect public funding for the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SRG SSR). The motion was overwhelmingly, rejected by 72% of voters. This was a significant endorsement of the fundamental purpose of PSB stress-tested in the public arena.

The reasons for recent changes are varied. Denmark’s shift was motivated by opposition to the level of the fee and the advantage it was seen to afford PSBs. In Sweden, it was driven by fears surrounding the fee’s outdated terms and its inefficient collection (evasion hovered between 11% and 15%). The new Swedish fee is charged to individuals, not households, proportional to income and capped.

Where there is a low willingness to pay for the licence fee, these conditions have sometimes led to a rethink of the licence by reforming or remodelling its scope. In Germany in 2013, the licence fee was changed from one linked to devices to a household levy. In Italy, in 2016, the fee was added to utility bills to prevent widespread evasion. This was challenged by the European Commission and the Italian Government is looking for an alternative.

Compare all this with the BBC’s position: evasion is low, indicating that the collection method is appropriate; and the licence fee is good value compared with other paid-for UK alternatives and Western European equivalents. To date, there are no PSBs that have adopted a subscription model or a paywall, as these are incompatible with universality.

France provides the most pertinent and analogous situation to the challenges facing the BBC and Channel 4. As part of his successful campaign for re-election, President Macron promised to scrap the licence fee.

This policy was poached from his leading centre-right rival, Valérie Pécresse, and justified by the squeeze on French households at a time of rising living costs. Although no specific replacement for the licence fee was proposed, Macron’s allies have indicated that future funding will come from the state, under a multi-year programme.

France’s licence fee, charged to TV-set owners, is relatively low, at €138 per year, as against €191 in the UK. Many households are exempt: only 22.9 million pay the fee out of a total of 27.6 million TV homes. The largest exempt group are low-income households with one member aged over 60.

'Before even considering the sufficiency of PSB funding mechanisms, the transition from linear to digital and on-demand has shown the potential to unravel national television ecosystems.'

The state pays France Télévisions (FTV) an annual contribution to offset these exemptions. Overall, in 2022 the licence fee is expected to generate €3.14bn in revenues for FTV alongside €561m in state contributions. By comparison, the BBC’s licence-fee revenue for 2021 was €4.5bn.

FTV also carries advertising in the daytime, which generated €352m in 2019; the broadcaster’s finances have yet to recover from the decision taken to halt advertising in 2008 by President Nicolas Sarkozy, and only partially carried out.

How would tying funding to the state alter FTV? Without explicitly opposing the president’s plans, FTV’s CEO, Delphine Ernotte Cunci, has pointed out that “predictable and consistent” resources are necessary to the broadcaster’s independence. In other words, the broadcaster needs to pursue a long-term investment strategy, and, crucially, to be shielded from partisan pressure on news and current affairs. An organisation obliged to plead for funds from the government will find itself in a weak position when it comes to resisting editorial interference – a key issue in a country where all other major media are owned by commercial interests.

This is compounded if the settlement is only for one year, with no certainty of income beyond that point. The risk is elevated in a country with a history of government pressure on media and a journalistic culture of deference towards politicians. FTV may already be under the Government’s thumb. Close to 15% of its revenue is a discretionary budget allocation from the state. This is hardly an argument for even more discretion.

More worryingly, FTV is in a weak position to defend the licence fee because it has failed to build public support for it. Echoing British political rhetoric, the anti-licence-fee right says FTV lacks pluralism, while the left deplores what it sees as populism.

Annual budget reviews also risk undermining ambitious drama projects, such as 2021’s Zola adaptation, Germinal, which are easier to cut than the massive in-house wage bill.

Traditionally, the French government has been preoccupied by supporting domestic production and has taken the lead in Europe in promoting regulation to force international SVoD platforms such as Netflix to invest in European content.

However, the Government has revealed its policy blind spot: its conception of an audio-visual industry modulated exclusively via regulation overlooks the crucial institutional role of broadcasters in steering quality projects. From HBO to the BBC, via RAI or ARD, experience shows that high‑quality production cannot emerge without demanding commissioners.

What does this change mean for Europe? There are layers of threat to consider. Before even considering the sufficiency of PSB funding mechanisms, the transition from linear to digital and on-demand has shown the potential to unravel national television ecosystems. The global tech giants’ control of interfaces and content discovery paths is pushing European providers down the supply chain. Only consolidated commercial broadcasters have sufficient scale to steer national markets towards digital models. Only then can European content providers retain prominence and their ability to set the popular cultural agenda.

We have already seen mergers in France (TF1 and M6), the Netherlands (RTL4 and Talpa) and Belgium (RTL and VTM). The PSBs may well be caught in this consolidatory slipstream (this may be the outcome of Channel 4’s privatisation). All this points to declining pluralism, and, probably, independence and competition.

Claire Enders is the founder of Enders Analysis.