As the BBC screens Then Barbara Met Alan, RTS Futures considers if life is improving for TV’s disabled workforce.

Watching two disabled people make love on prime-time terrestrial TV is something many disability campaigners thought they’d never see. But last month, in BBC Two’s widely praised drama Then Barbara Met Alan, we witnessed the eponymous Barbara and Alan enjoy being intimate in a scene that may well go down as one of the most powerful and moving moments of TV drama in 2022.

Then Barbara Met Alan is a rollicking, neo-punk love story – Barbara is a comedian and Alan is a musician – interlaced with another story, the battle for disability rights. This is a little-known piece of history that failed to achieve the cultural cut-through of, say, Roy Jenkins’ social reforms of the 1960s, including gay rights, which may tell us something about common social attitudes to the disabled.

Barbara Lisicki and Alan Holdsworth were the founders of disability activism group DAN. The campaign for basic rights for the disabled led to the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, which, as the film highlights, was only the beginning of changes in the law that would eventually improve millions of disabled people’s lives. This belated piece of legislation had to be fought hard for.

The film recounts the exhilarating story of how disability rights campaigners took to the streets (and the TV studios – an early target was ITV Telethon 90 and 92, which the protesters who went on to found DAN in 1993 regarded as utterly patronising). They were claiming the right to do what most of us take for granted: things such as being able to get on to a bus or use a public toilet, never mind disabled access at restaurants and venues.

The film was co-written by Genevieve Barr and Jack Thorne, the prolific screenwriter and disability advocate and recent winner of the Single Drama prize at the RTS Programme Awards for his Covid drama Help.

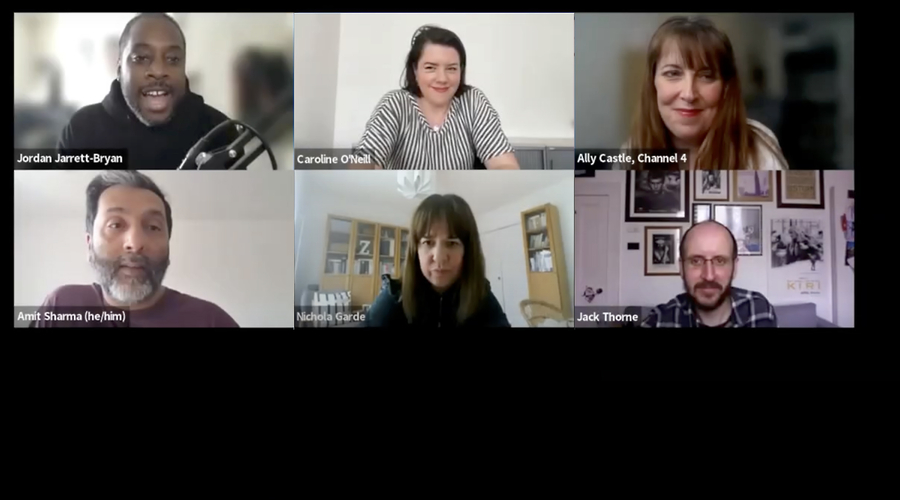

Thorne told an RTS Futures event, “Disability and the TV industry: All change?”, that Then Barbara Met Alan’s high profile was another sign of an improved attitude and working conditions for disabled people who work in television.

He was asked by session chair Jordan Jarrett-Bryan, who works as a sports reporter for Channel 4 News, whether the TV industry was somewhere that harnessed, developed and enabled disabled talent to flourish and have a thriving career.

“It didn’t used to be those things. The hope is it’s changing,” said the screenwriter. “It feels like it’s changing. Over the past year, we’ve seen an enormous amount of progress from all the broadcasters… ScreenSkills is training accessibility co-ordinators who will be on set. That will make a huge difference. [But] more than any of that, it’s the attitude that is changing.”

The BBC’s handling of Then Barbara Met Alan illustrated his point. Director-General Tim Davie had hosted a screening, the film was given a 9:00pm slot on BBC Two and followed by a marketing blitz to encourage audiences to seek the programme out on iPlayer.

Thorne told the RTS this was in complete contrast to his two previous TV dramas that dealt with disability themes. They were pushed to the margins of the schedules: “It was like wading through glue. It was impossible to get any attention for them…

“Hopefully, the attention given to Then Barbara Met Alan is part of a change in getting disabled stories told by disabled people on screen. That means that people who are coming into the industry are coming into an industry that has an appetite for their work.”

Significantly, many of the production staff on the film were themselves disabled. Co-director Amit Sharma was asked what it was like working on a show with so many disabled people. “I’ve done large-scale theatre with disabled people in the UK and internationally, with audiences of 6,000 people, so coming off a set where so many people identified as deaf, disabled and neurodiverse felt really natural,” he said. “We created a culture on set where people felt safe. They started to declare their impairments… Everyone wanted to learn about sign language…We worked hard to make a joyful atmosphere. It was buzzing.”

Jarrett-Bryan asked panellist Ally Castle, Channel 4’s creative diversity and disability lead, if she could tell that Then Barbara Met Alan was made by disabled people and not just about them? “Absolutely,” she replied. “The tone of it was just right. It captured the real chaos of that movement, which was needed to get it noticed. The lack of concern about using the C-word was a beautiful thing.”

Nichola Garde runs the BBC’s Elevate scheme, which aims to remove some of the barriers, attitudinal as well as physical and cultural, that make working in TV challenging for deaf, disabled and neurodiverse people. Of Then Barbara Met Alan, she said that, “although it was amazing to be working with on-screen disabled talent, the real shift for them was working with off-screen disabled and non-disabled talent. Creating a safe space where everybody could learn from each other and have some fun was so important.”

While the situation in the production space may be improving for disabled people, television still has a mountain to climb in appointing more disabled men and women to senior industry roles. Michael Grade, Ofcom’s next Chair, acknowledged there was a problem when he was interviewed last month by the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Committee. Grade said it would be a priority for him to have more disabled people on company boards.

Series director and executive producer Caroline O’Neill agreed. She is also co-director of Deaf and Disabled People in TV (DDPTV). She told the RTS that people with power needed to exert their influence if change for the better was to continue.

“If you’re a senior person in the industry, you have a responsibility to bring people in and not just a white disabled person,” she said “It’s harder to be more diverse but if we don’t take more responsibility, we can’t change the shape of the industry. We can’t just talk a good game about it, we have to action it.”

O’Neill added: “I’ve been in the industry for a long time, [and] we’ve not been allowed to prosper as others have. If you’re a disabled person, you’re held back in your career. People like to cast in their own, white, male mould.”

It is widely acknowledged that Channel 4’s commitment to disabled representation on screen has been pioneering. Think of its coverage of the Paralympics and shows such as The Last Leg. However, Ally Castle struck a cautious note when she said, “So often, I still feel we’re in that space where we’re hiring disabled people despite them being disabled.

“But our message at Channel 4 is that you should hire people because they are disabled. This whole ‘I don’t see colour, I don’t see disability’ is not very helpful because then you can’t make the right adjustments to understand where this talent is coming from.

“We say: hire disabled talent because they are not only going to help you connect with your audience – on paper, 20% of whom are disabled – but they bring with them so many skills and life experiences...

“I want disabled people to be proud of being disabled and to say: ‘This is what I am bringing to your production.’ We want our indies and our broadcasters to recognise all the great value that they bring.”

And more shows of the quality and vigour of Then Barbara Met Alan, please.

Report by Steve Clarke. ‘Disability and the TV industry: All change?’ was an RTS Futures event held on 22 March. The producer was Gaby Hornsby, TV lead for sustainability at the BBC.