As the RTS celebrates its 90th anniversary, we looks back at the evolution of a unique organisation.

‘Recalling the early days of television and the Society, and then looking at things today, may be rather like looking at an acorn and then the oak tree and wondering how it all happened.” WC (Bill) Fox’s words from 40 years ago, on the occasion of the Society’s 50th anniversary, illustrate what television felt like to him in 1977. The Press Association journalist was present at the start of the Society – and even at the birth of television itself, as an enthusiastic supporter of John Logie Baird.

Four decades after Fox’s “oak tree” speech, television has changed almost beyond recognition. Developments in technology have enabled new ways of producing and distributing programmes alongside better experiences for viewers.

Those changes have turned television productions into internationally marketable commodities. All through this, the Society has adapted as best it could to support the industry across all its disciplines.

John Logie Baird with his Noctovisor at the

British Association in Leeds,6th September 1927

(Credit: RTS)

Fox had supported Logie Baird at Frith Street in London on 26 January 1926 for what turned out to be the world’s first exhibition of “true” television.

In the summer of 1927, Baird again asked him for assistance, this time at a British Association meeting at the University of Leeds. Fox cancelled his holiday to help Baird with his demonstrations, and played his part at what was to become the founding meeting of the Television Society.

On the morning of 7 September, following a short speech in which Baird rounded up a week of demonstrations, WGW Mitchell of the British Association gave a vote of thanks. In a move that was undoubtedly preplanned, he proposed a motion to form a society “to further the progress of television and give a stimulus to this new branch of science”.

At that point, Baird’s focus was on developing a video-disc player and a night-vision system, rather than broadcasting.

The Society’s mission was refined to furthering “the arts and sciences of television”. Most people expected Baird’s new technology to become an extension of the existing sound broadcasting service.

The Society's early years

Television was still a very small acorn. It was little more than a curiosity – its hybrid mechanical-electrical approach rested on a foundation of 19th century inventions, and its output was crude.

Within a year, however, Baird had improved his picture, and, in March 1930, he launched an experimental sound and vision service paid for and operated by the Baird Company and broadcast over BBC transmitters.

The Baird Company’s influence on the Society ran deep in those early years. This was hardly surprising, as no other person or company so actively promoted television.

the Noah's Ark receiver in 1929

(L-R Reg Shaw, WC Keay, Lulu Stanley DR Campbell

and MA Calkin)

(Credit: RTS)

The advent, in 1936, of the BBC’s “high-definition”, all-electronic London regional television service, which used 405 lines, completely overshadowed Baird’s earlier groundbreaking, low-cost mechanical systems.

Reflecting the state of the industry, the Society was initially the primary independent technical forum for radio dealers and electronics enthusiasts. By the 1950s, this included the equipment manufacturers, many of whom became the Society’s first major sponsors.

The Society’s chairmen and presidents – men such as the outspoken Sir Robert Renwick – were senior figures in the industry. They spoke with authority, and hammered home the message that broadcasters and government should ensure that “television be made available to all”.

As broadcast television was rolled out across the country in the early 1950s, the Society’s focus was, quite naturally, on the rapid development of engineering systems that enhanced the service, first with higher definition and then colour.

Such persistent emphasis on engineering seems surprising today, given the input of many disciplines to programming. One explanation may be that, in an era of a single channel, the government-supported BBC Television service handled production internally.

Of necessity, the Society continued to reflect the needs of the equipment and systems suppliers by providing a platform for sharing the latest developments in technology.

Unsurprisingly, both leadership and membership largely reflected engineering interests. The arrival of commercial television in 1955 did little to change matters. By the 1960s, the Society’s continuing concentration on technology meant that it failed to reflect the breadth of views in the overall television community.

Its saving grace, however, was the valued open forum that the Society offered to the various industries that supported broadcasting. The fledgling Television Society – it gained its Royal prefix in 1966 – deliberately avoided taking sides in any controversies aired in the forum it provided. Its impartiality has continued to be a fundamental feature of the Society, earning it great respect from sponsors.

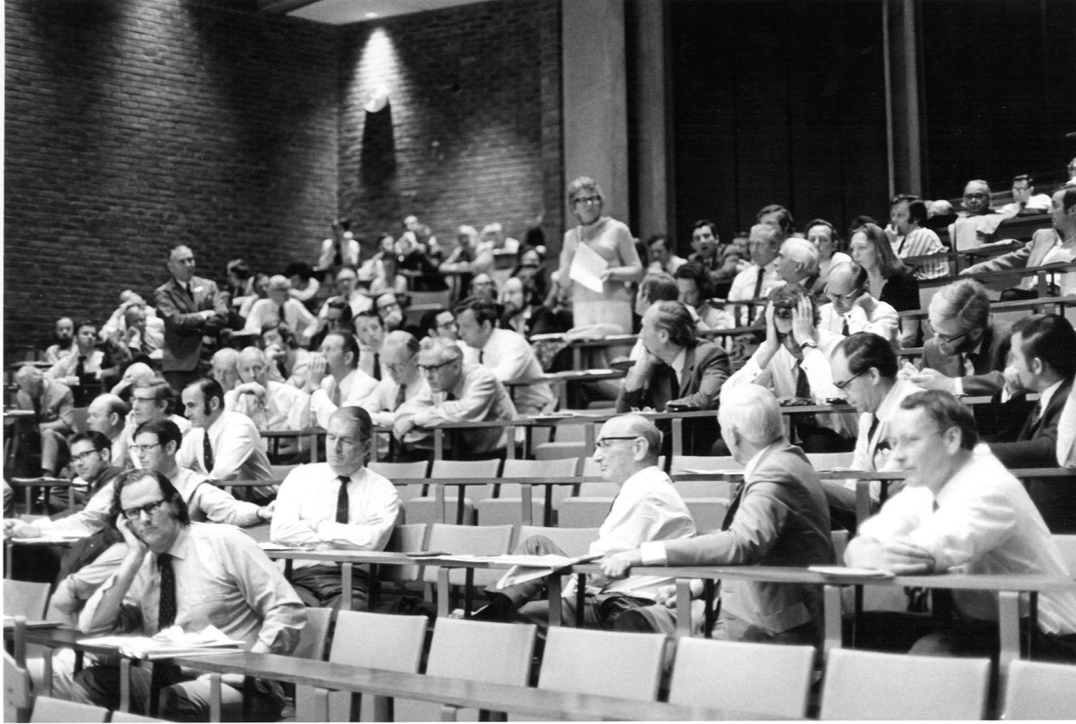

Encompassing programme-making

(Credit: RTS)

Small steps in the 1960s were followed by more insistent efforts in the 1970s to broaden its scope. Engineering was important, but, after all, television would never have developed beyond the laboratory without programmes that attracted audiences. These viewers, in turn, generated revenues from TV licences – and, in time, advertising and subscription.

The repositioning of the Society to encompass the broader programme-making business, together with a recognition of TV as a public service enabled by technology, made the organisation increasingly relevant to major industry stakeholders – especially those involved in production.

Broadcasting was developing rapidly as a business. The early mentality of low-cost production, which verged on “make-do and mend”, gave way to bigger programme budgets for more ambitious shows. International sales and co-productions became commonplace, as did the outsourcing of production to independents, driven by the free-market agenda of the 1980s.

A modern society

From 1970 onwards, the Society’s Cambridge Convention has provided a venue to debate every aspect of the business. It has consistently attracted senior representatives from the broadcasters, platform owners, producers, policy-makers and government. The RTS Cambridge Convention alternates with the biannual RTS London International Conference.

The Society’s achievements over 90 years are not restricted to bringing the television community together: it has encouraged new talent, and its national and regional awards have recognised excellence in front of, and behind, the camera.

(Credit: RTS/Paul Hampartsoumian)

The first of these were the Pye and Colour Awards for production. The RTS Programme Awards were introduced in 1975, followed by the RTS Television RTS Journalism Awards in 1978 and the RTS Craft & Design Awards in 1987.

From its inception, the Society has supported the development of specialist skills unique to television. In 2007, it launched the RTS Futures programme of events, workshops and masterclasses to assist young people who hoped to work in the industry. RTS bursaries have also helped young people train for careers in television.

The RTS is one of six shareholders in IBC (International Broadcasting Convention), which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

Television today is a complex and dynamic global phenomenon far removed from the nascent technology that the Society was set up to promote. Over 90 years, the RTS has evolved to reflect the changing needs and aspirations of the UK’s television industry.

Fox’s “oak tree” has matured: now imposing, its branches of technological and cultural achievement spread high and wide; new saplings sprout all around it. Some may just have been in Baird’s dreams when he planted his acorn.

Based on an article by Don McLean

To celebrate the Royal Television Society's 90th anniversary, a day of events will be held in Leeds, where the Society was founded, in November. Click here to find out more.