On the centenary of John Logie Baird’s demonstration of the Televisor, Simon Bucks imagines what television might look like in 100 years’ time

Try this thought experiment: time-travel to the year 2125 and imagine watching TV. What is it like? Now buckle up for a mindbending vision from Google’s Director of Emerging & Enterprise, Faz Aftab: “Neural interfaces could bypass screens altogether. The narrative would go straight to your brain via a neural implant.”

Isn’t that a bit mad? “Thinking about 100 years’ time, I don’t dismiss anything. Elon Musk is already trying this with Neuralink,” says Aftab.

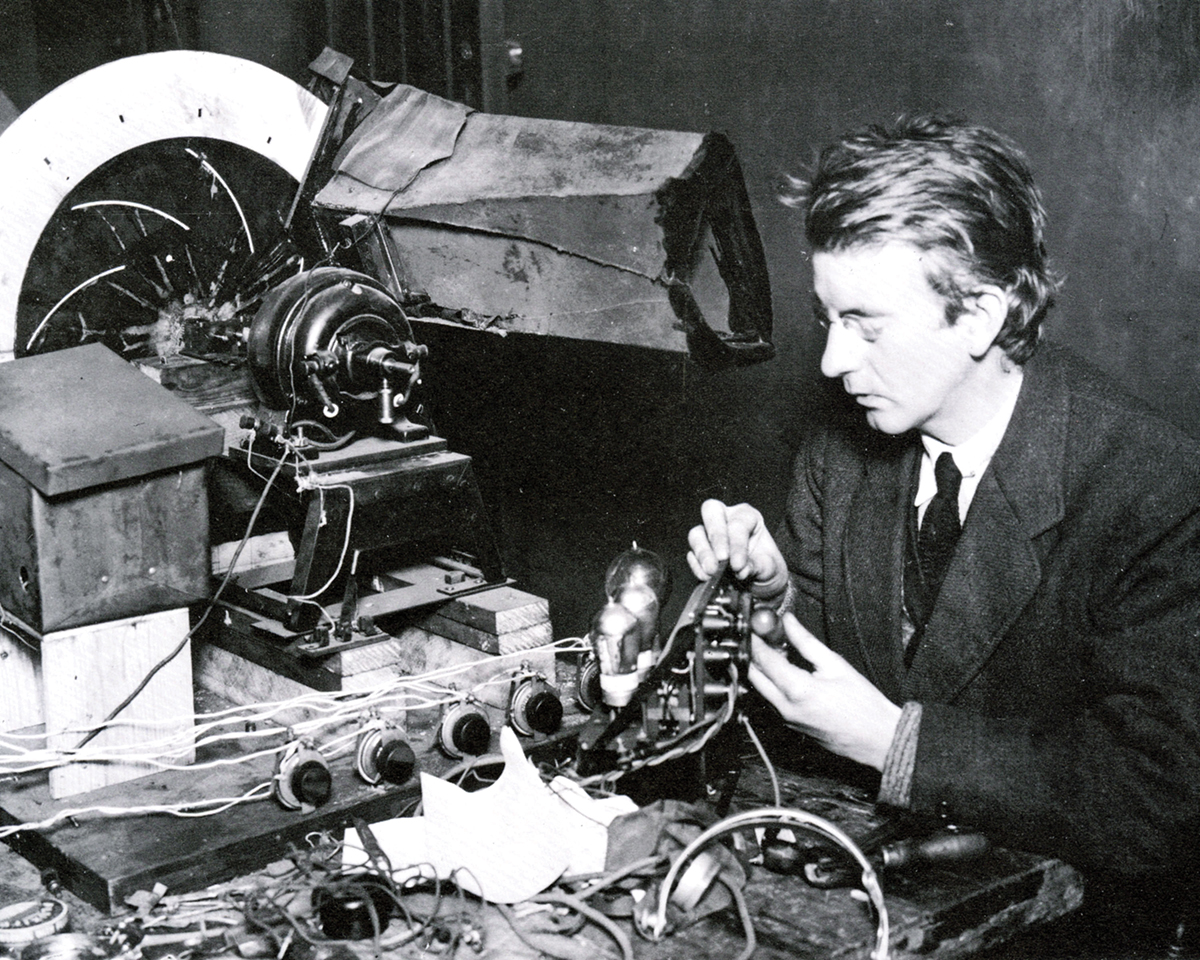

Predicting the long term for what we today call television is undoubtedly hazardous. When “Father of TV” John Logie Baird tried to persuade the Daily Express to take him seriously, the news editor apparently barked: “Get rid of that lunatic. He says he’s got a machine for seeing by wireless. Watch him, he may have a razor.”

Undaunted, 100 years ago this month, Baird was at Selfridges in London’s Oxford Street, demonstrating his “Televisor”, a Heath Robinson contraption of bits and bobs, including a tea chest, cardboard and bicycle parts. Initially, it only produced shadowy silhouettes, but it wasn’t long before Baird had perfected a 30-line system to transmit recognisable pictures with synchronised sound.

Soon afterwards, in 1927, Baird was a key figure in the formation of the infant Royal Television Society.

Could he have imagined 2025 TV, with its wafer-thin, wall-sized, 16k screens, infinite channels delivered via the internet, AI-generated content and the power to inform and entertain billions? His grandson, Iain Baird, a TV historian, thinks he might have done. “He got pretty close with the Telechrome to where we are today with colour television. He demonstrated a two-colour version and would have had a three-colour one if he had lived beyond 1946. He would have seen digital compression as a natural progression of what he was trying to do, to get more realistic pictures. He even had the idea of doing 3D.”

Today, Google’s Aftab says the pace of change is so rapid that genuinely immersive, virtual reality TV is close. “You could be watching The Traitors, and the letter ‘I’ would appear on screen, and you would put on goggles and be able to walk round the table like Claudia Winkleman does. And my daughter could put on her goggles but have a different experience.”

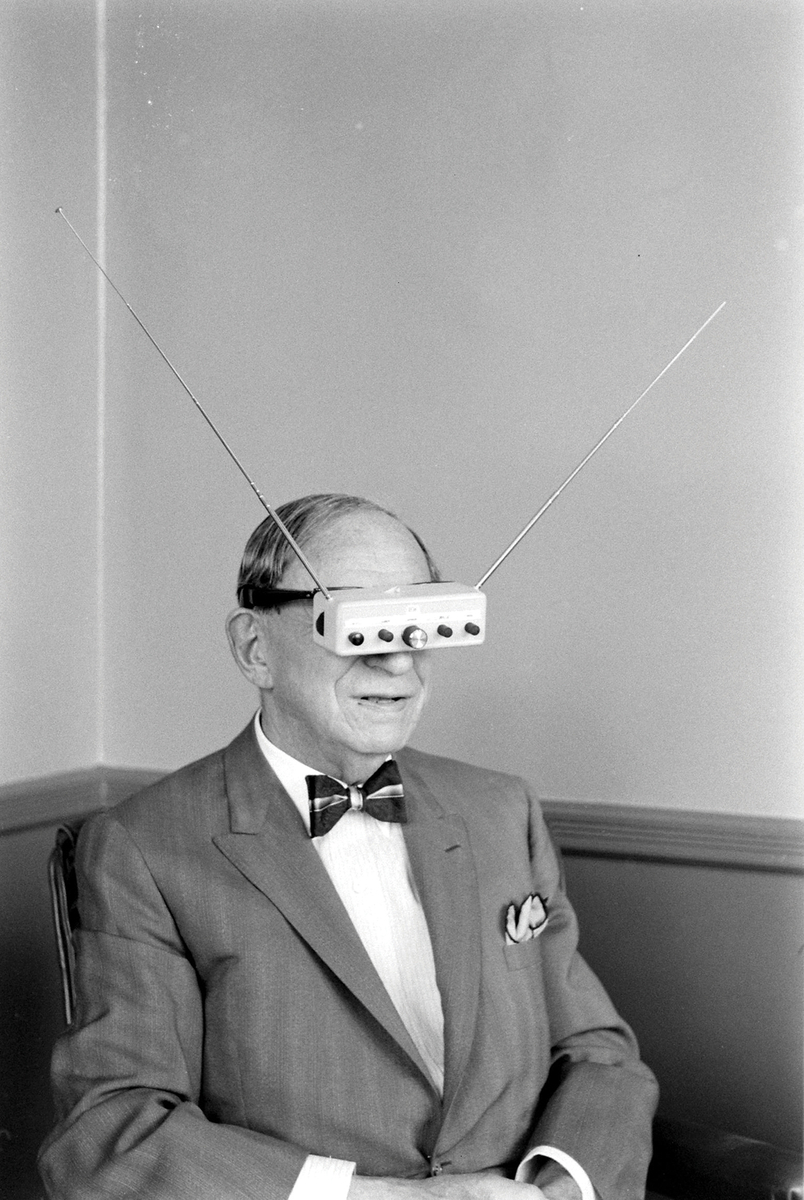

If that sounds like science fiction, remember the prescience of veteran sci-fi pioneer Hugo Gernsback. “Movies by radio! Why not?” he demanded in 1925. His magazine Radio News imagined a future TV set resembling an Edwardian-style dressing table. He even demonstrated prototype goggles strapped to his head.

Sci-fi certainly inspired John Logie Baird, says his grandson. “He read HG Wells and the science fiction magazines. He would have loved Doctor Who and Star Trek – anything technical.”

So, what do today’s Gernsbacks think 2125 will bring? It’s all about physics, contends Allen Stroud, Chair of the British Science Fiction Association and a Coventry University academic, whom the Ministry of Defence has consulted for ultra long-term forecasting. “The issue is not about how much data we can push but how fast we can push it: latency. We can’t get past the speed of light.”

And yet, concedes Stroud, physical laws may already be bending. “There was research recently where they had some quantum states where light particles were affecting another particle before they made contact. So, it seemed to be negative time, which was, kind of, wow!”

“Quantum messes with my head, but it’s real,” agrees Richard Lindsay-Davies, Chief Executive of the Digital TV Group and Chair of the Infrastructure Working Group advising the Government on the future of UK television. “An academic told me you’ll be able to spin up a quantum instance here and – with no connection – it will be matched 1,000 miles away, and they will just be the same.”

For TV technologists, the big thing is “form factor” – the capacity, size and shape of components. For the non-scientist, all you need to grasp is that they are constantly getting smaller, faster and more efficient.

“I don’t see technological advances slowing down,” says Paul Kane, ITV’s Director of Technology, Content Supply and Distribution. “I remember attending partner meetings with Arm, the semiconductor firm, and they were predicting 7 and 5-nanometre chips. Now we’re talking about 3, 2 and even 1-nanometre chips, a billionth of a metre, and at this point we’re breaking some of the perceived laws of physics.”

“In 100 years, TV will be almost invisible,” thinks Iain Baird. “You might have a TV which is basically your clothing. The barriers will disappear in terms of portability, recordability and visibility of television.”

TV will be invisible. You might have a TV that is basically your clothing

So, by 2125 we may have debunked Einstein and built semiconductors you can’t see, but what will it actually mean for viewers? More immersion, predicts Lindsay-Davies. It will be the natural progression made possible by faster computing and fewer technological constraints. “I wonder if we might even have the technology to allow us to experience those additional senses beyond video and audio, like temperature and smells,” he says.

Haptics, the science of reproducing physical sensory experiences remotely, will be possible over virtual reality television, confirms Stroud, with AI’s interpretative capabilities helping smooth over any latency hiccups. Cooking programmes, for example, could become a participatory experience for viewers. “You just have to find a way of accessing people’s taste receptors using chemicals.”

Aftab at Google thinks that haptics will be perfect for sports events and concerts. “If you could pump in the sense of smell and taste of people around you, it would give that feeling of being in the crowd.”

More personalisation is coming, agrees Lewis Pollard, Curator of Television and Broadcast at the National Science and Media Museum. He points to BBC Research and Development’s “Object-Based Media” project, which, theoretically, would enable every viewer to get different versions of the same show. “A programme can be split up into all its constituent pieces and reshaped. Some parts can be made longer, some shorter, to appeal to you as an individual,” explains Pollard.

The project began more than a decade ago but remains in the laboratory. That won’t surprise Paul Lee, Head of Research in technology, media and telecommunications at Deloitte. “I don’t see the TV screen changing very much. In 100 years, people will still be watching with other people. I don’t see it becoming more immersive,” he says.

“Technology is often written about as if it’s autonomous and it absolutely isn’t. Technology only thrives when humans thrive as a result of its application. Its adoption is always going to be constrained by the extent to which people can change behaviour.”

Lee isn’t alone in being sceptical about immersion. “The multipath concept is interesting, but you have to be an active participant in the experience,” says ITV’s Kane “And I’m not sure people really want that – they want to relax and be entertained.”

(credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt/

The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock)

“I don’t like goggles. They make me nauseous,” says Jeff Jarvis, the veteran American media academic and former TV critic. “I don’t think they are going to be as big as Mark Zuckerberg does.”

Yes, the technology is still too young, concedes Google’s Aftab, but it will get better. On a 100-year horizon, she thinks the answer will be “holographics” or “volumetric” displays which project 3D pictures without goggles or even a screen. “You could be watching rugby with it playing around you, and you’d be immersed in it. It’s totally achievable. By immersive, I don’t mean just eyes. I mean everything.”

Lindsay-Davies agrees: “We’ll have technologies for a deeper immersion in the content without it being 3D or a full virtual experience or wearing glasses. It will be much more tailored to individual needs and pretty seamless. We won’t realise that we are getting a very personalised experience.”

Maybe, says ITV’s Kane, who experimented with “holographics” at Sky more than 10 years ago. “But for me, it’s still about content and storytelling. It’s still about sitting down and having a communal experience.”

Deloitte’s Lee adds: “Being entertained along with other people is a fundamental human need. People watch funny videos on FaceTime, and they time it so that they look at their phones and laugh together. That’s humans being human, and that’s not going to change in 100 years.”

Jarvis has doubts. “The grand shared experience was a myth. When I grew up we had only three networks, and you might think it was fun to watch [US sitcom] Gilligan’s Island together. It wasn’t. It was hell – but it was all we had. The future is one of collaboration, interactivity and discourse. Pay attention to TikTok because of its collaborative nature. Even if it isn’t there in 100 years, its essence will be.”

Jarvis’s US compatriot Michael Rosenblum, the video journalist guru and TV innovator, argues that existing TV models are broken and ripe for reinvention. “Everyone will have the tools to make video. This vast democratisation is similar to the impact on society of the printing press. It was the end of the supremacy of the Catholic church and feudalism, and the beginning of the Enlightenment.”

If this all sounds scarily dystopian, relax. Lindsay-Davies is confident that, in 2125, our descendants will be watching TV, one way or another. “People will still want entertainment, sport and news. However, the word ‘television’ may feel outdated, so it could be called something different.”

How about the Televisor?