Narinder Minhas savours a new book that is a love letter to the long-form interrogation of politicians by broadcasters.

I like this book. No, wait – I really like this book! There you have it. The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Or is it? How can we distinguish the truth from a bald-faced lie? Am I, the reviewer, telling fibs just as brazenly as a seasoned politician?

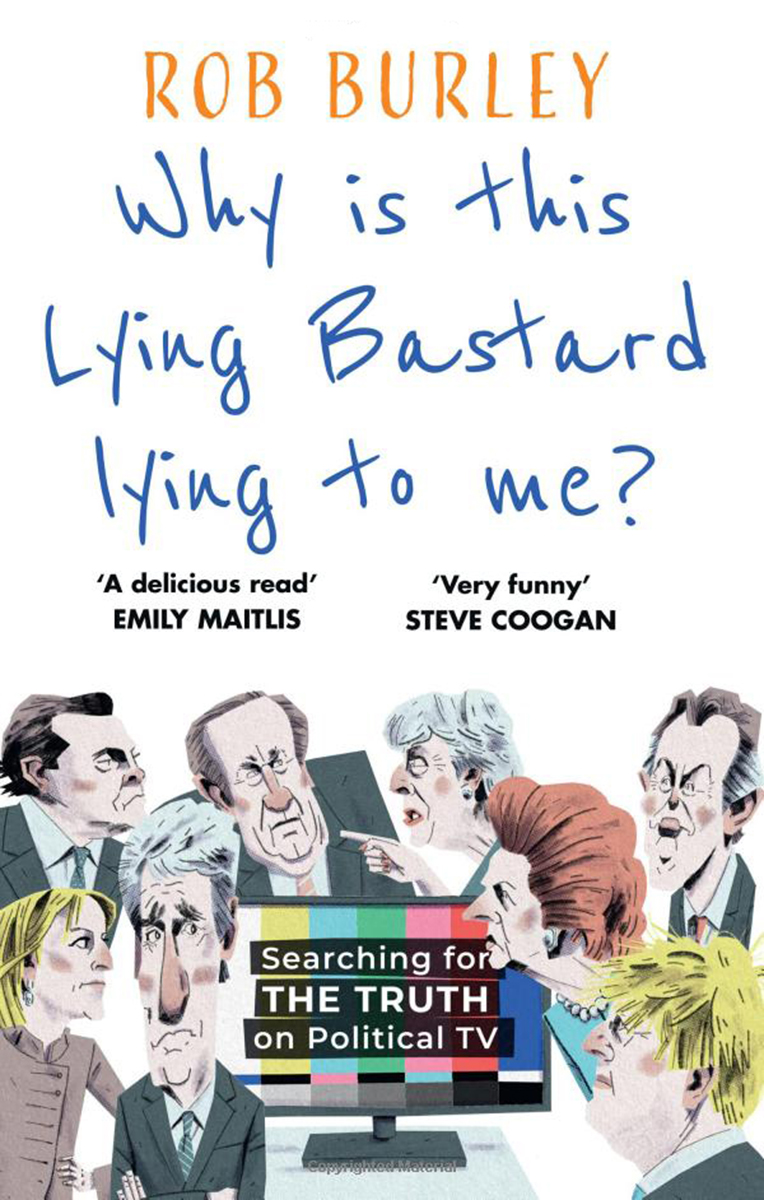

Joking aside, the truth is this: there is much to admire about Rob Burley’s new book, Why Is this Lying Bastard Lying to Me? Searching for the Truth on Political TV. Part biography, part post-war history, and part love letter to the long-form political interview, it is jam-packed with anecdotes and wisdom from Burley’s 25 years as a top producer in political broadcasting. He also tackles perhaps the most elusive thing in his line of work: the truth.

The big problem is that lies are everywhere – on social media, in CVs, in boardrooms, on dating apps and, of course, in politics. There are many different ways to lie. Burley kicks off with a fascinating nugget: academics have identified 35 different ways in which politicians can avoid answering a question – from “acknowledging the question without answering it, questioning the question, attacking the question… making a political point instead of answering the question, repeating the answer to a previous question” to just blatantly ignoring the question.

In this last category, Boris Johnson was a prime culprit. He brazenly escaped into an industrial walk-in fridge to avoid a Good Morning Britain interview. These are dark and cold times indeed.

So, what is the best route to the truth? Perhaps it really is the long-form political interview – and Burley provides an absorbing account of the titans of this skill, from Robin Day to Brian Walden, Jeremy Paxman to Emily Maitlis.

In one gripping section, Burley expertly narrates one of the most iconic interviews from the past 50 years: Walden vs Thatcher. The show: The Walden Interview, 1989. Unusually, Thatcher’s guard is down. Walden is an admirer of hers, almost a friend, almost a confidante. She expects things to go her way.

But the interview plays out like a political psychodrama. Trust is betrayed. Expectations are shattered as Walden turns rottweiler. Burley’s retelling feels like a movie script, capturing their interaction brilliantly, with all its nuances. I’m not saying it is Frost/Nixon, but it would make a fantastic film, perhaps with Michael Sheen playing Walden.

These kinds of interviews are no mean feat. They are an art form in themselves, involving enormous levels of preparation. I should know; I was a researcher on Walden’s other great show, Weekend World. The document we had to prepare for each interview was exhaustive and exhausting.

Not only did it need to include the key questions, but also every likely response to them. The whole thing would have “the underlying shape of a family tree” – if the minister says no, go to question seven. If the minister says yes, go to question 10, and so forth. Things can go sideways quickly in these interviews, and it is essential to be well-prepared.

Burley knows this all too well – especially when the interviewee is prepared to use a particularly sneaky tool: lying. In one compelling anecdote, Burley recalls an interview in 1997, in which Jonathan Dimbleby accuses Lib Dem leader Paddy Ashdown of making promises he can’t keep. Ashdown wants to increase spending on education by raising income tax.

Dimbleby argues that this money can’t possibly be ringfenced for schools. After all, Ashdown can’t control where local government spends its money. Ashdown pushes back: “Wrong, wrong, wrong.” He says Dimbleby has been “badly advised” by his researcher, and it’s all “in the detail of the manifesto”. Burley, the shamed researcher, scrambles to prove Ashdown is incorrect, flicking through the manifesto in a panic. But it’s too late. The interview has moved on. Later, at the post-show drinks, with a laugh, Ashdown brazenly admits to lying.

It is these moments – often funny, sometimes disturbing and, occasionally, very moving – that give this book its delicious insider feel. It brims with wonderful testimony, founded on great access.

The insights from Paxman are particularly entertaining, and Burley has high praise for him. Paxman is “allergic to being boring”, and his “apparent contempt” for his interviewees is addictive to watch.

Paxman was determined to get to the root of an issue. This is typified by his famous Newsnight interview in 1997 with Tory politician Michael Howard. The subject matter wasn’t anything special. But, confronted with Howard’s stubborn elusiveness, an exasperated Paxman asked him a single question 12 times. A bold tactic and a far cry from where we are today, with Liz Truss getting away without doing a single set-piece interview yet still being elected Prime Minister by her party. What kind of precedent does that set?

While Burley’s takes on these big moments in political interviewing form a hugely enjoyable chunk of the book, he also treats us to many left-field insights gleaned from working behind the scenes on some of the biggest political shows. Burley says that being the editor of BBC One’s The Andrew Marr Show was the best job of his life.

During the awkward meet and greets before interviews, which he hated, Burley was exposed to the varying ways in which politicians deal with small talk. I find it amusing how perfectly he has encapsulated the different characters. David Cameron: “aloof” and self-important (sure, he was PM, but “there was no need to be a dick about it”). Jeremy Corbyn: less interested in Burley, and more so in the excitable junior staff members. Theresa May: completely and utterly devoid of small talk.

I would have welcomed a few more facts or figures along the way, such as who is the least honest prime minister in history? What is the average number of lies in an election campaign? Or some more research from the social scientists. But, then again, practising what he preaches, Burley is clear from the outset: “This is not a textbook.” It is, however, an incisive, unflinching, funny and much-needed interrogation of what political TV looks like in the world of post-truth politics – and how on earth we got here.

Burley seems nostalgic for the golden age of political interviewing. Gone are the days when politicians felt a duty to show up, undergo a grilling, and endure the brutal media takedown in the papers the following day. Nowadays, politicians seem to grant the interviews where they will get the easiest ride. Burley is tentatively optimistic about Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer, but it’s clear that the long-form political interview is an endangered species.

Why this sea change? Obviously, there is so much more choice than the three or four channels available in Day’s time. The Sunday morning TV political slot has sadly lost its resonance, diluted across today’s myriad platforms. And, of course, social media has completely changed the game. Why would a politician risk their credibility in a fierce interview, when they can control their message on Twitter?

Burley’s book strikes a perfect balance between accessibility and serious analysis, and carries an important message.

What he has laid out here truly matters, and we need to continue to demand the truth. As Burley says, we deserve it. For any politicians reading, there is a way to decline an interview with dignity. But just a clue – it doesn’t involve climbing into fridges.

Why Is this Lying Bastard Lying to Me? Searching for the Truth on Political TV by Rob Burley is published by Mudlark, priced £16.99. ISBN: 978-0008542481

Narinder Minhas is founder and CEO of Cardiff Productions.