From the unparalleled three-way race of 1992, to the Bush v Gore recount which went to the Supreme Court in 2000, CNN’S Chief National Correspondent John King has witnessed some extraordinary events over the nine Presidential elections he’s covered.

The Inside Politics anchor admits once naively assuming he had seen all the ‘wild roller coaster elections' history could throw at him.

“I thought, I’ve been through all the crazy, right? There’s nothing that’s going to surprise me,” he says. “How many times as a journalist do you get the gift of a story so dramatic and compelling? But this one was…wow.”

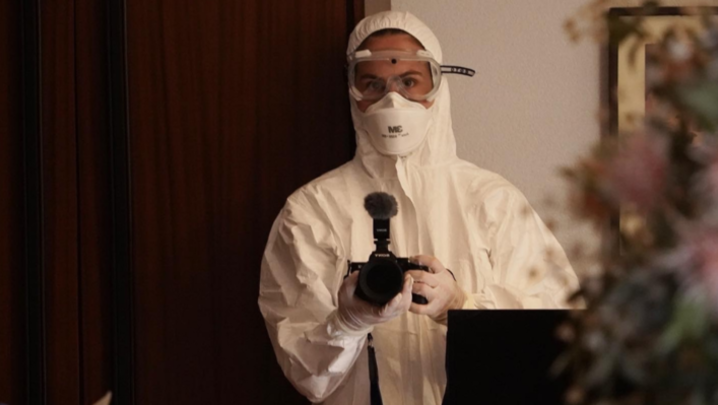

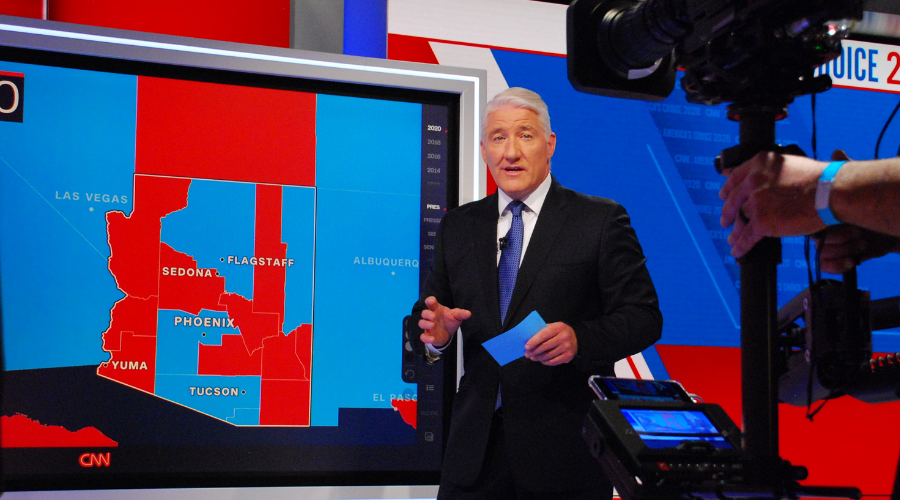

Despite over 33 years of experience in what King terms ‘the curiosity business’, nothing could have prepared him for the pandemic-induced, gruelling five-day marathon that would see him commanding CNN’s interactive US map known as the ‘Magic Wall’ for over twelve hours a day.

“Some people will say that I knew it was going to take five days, [they are] lying,” King laughs. “It was pretty clear to me based on all the data that we were not going to know on Tuesday’s election night. But I was of the firm belief that 24 hours later we should know. And of course, it wasn't until Saturday. So that was wild.”

five consecutive days (credit: CNN)

With his trademark levelheadedness, King relayed the facts and guided an anxious global viewership through an election like no other. His stellar work has resulted in the journalist becoming the first ever international nominee for the Network Presenter of the Year award at the RTS Television Journalism Awards.

Viewers were spellbound by King’s faultless off-the-cuff analysis, despite a seemingly impossible lack of sleep. As the hours turned to days, and the days nearly became a week, King maintained his reporting tenacity. “The complexity of it and the drama of it - once you’re on to a good story, you want to see it through to the end,” he enthuses. “I’ll use the word exhilarating, but it was exhausting as well. You forget your exhaustion by the end.”

While he’s famed for his number crunching and quick maths, King was more captivated by novels than numbers at school. He majored in English and initially considered pursuing teaching or law. “I loved Shakespeare, I loved to write. I was okay at math, but I didn't like math, and look where I end up,” he jokes.

Fitting then, that King’s first major posting involved covering the corruption and Macbethian machinations at the heart of Rhode Island’s state legislature. “We had great crime drama, political corruption, organised crime, the mob,” he explains. “All of a sudden, I realised they’d pay me to cover great human drama and great political drama, and I fell in love.”

Fundamental to King’s continued love-affair with his career were the endless opportunities to explore America. Coming from “a family with very little money in inner-city Boston”, King describes all of a sudden “getting to see the 50 different complicated pieces of the puzzle: the farm states, the states with oceans and states that have giant forests, things I’d never seen before.”

"I was just like, wow, holy *insert expletive*, what am I doing here?”

Through his travels on the campaign trail, King has built up a national network of people on the ground who act as a sounding board to inform his analysis. Remarkably, he’s still in touch with families he met covering his first election back in 1988.

The journalist’s M.O. that ‘you can’t understand America by sitting in Washington’ explains his encyclopaedic knowledge of every US county’s voting patterns. Such rigorous reporting is the result of a career spent meeting and engaging with the real people behind the data.

“I got a text from an evangelical pastor in Pennsylvania on Election Day who said, ‘Don't count Trump out, I'm in a line that runs two hours long,’” he explains. “Sometimes something just clicks in your head. Wait a minute, the fisherman in Florida is saying the same thing as the pastor in Pennsylvania. So there's something happening here.”

While he’s renowned for his unflappable delivery, it's reassuring to discover that even King has been susceptible to bouts of imposter syndrome. He recalls a time as a nervous young journalist when he was forced to hold his own alongside titans of the industry.

“When I met Sir David Frost, I was trembling. He did an interview with Tony Blair and Bill Clinton, and then I did an interview in the same setting straight after. And I was just like, wow, holy *insert expletive*, what am I doing here?”

The news industry has undergone a dramatic transformation since the days when viewers’ only access to news were scheduled broadcasts with iconic broadcasters such as Frost, King notes.

“There was a time when you had to turn on the TV at a certain moment, it was all scheduled. There was no cable, there was no 24 hours a day, there was no internet,” he says. “Now we live in this age where, whether it's on Twitter, Facebook, or any social media, people can communicate back. And they should, we should have a relationship with our consumers. That doesn't mean our job is to give them everything they want. We still have to cover news.”

With a former president who openly attacked institutions with claims of ‘fake news’ and stirred suspicion towards mainstream media outlets, the pandemic has reinforced how deadly misinformation can be. For King, news channels such as CNN have a mammoth task of rebuilding trust among sceptics.

“The past president of the United States, frankly, was not telling the truth a lot during the pandemic. But if you're going to look into the camera and say the president is lying, well, 75 million people voted for him and he has spent years saying, ‘don't trust the media,’” he explains. “We need to have a relationship of trust with people and say, calmly and dispassionately, ‘I understand you've been told not to believe me - here are the facts.’”

“I think we've all learned lessons about defending the truth, fortifying facts, and defending institutions. A big part of that is defending your brand,” King continues. “Be cautious, because your brand is important. And if you lose that trust, it's hard to get back.”

“We're not going to have campfires with Trump supporters and Biden supporters roasting marshmallows together, it's just not going to happen"

While other political reporters are mourning the end of Trump’s presidency and his knack for sensational scandals, King is thrilled by the challenge Biden faces to unify a deeply divided country.

“The polarisation gap is the Grand Canyon of American politics. Joe Biden cannot fill it in. Nobody could in four years, it’s impossible,” King admits. “America is not going to become Kumbaya. We're not going to have campfires with Trump supporters and Biden supporters roasting marshmallows together, it's just not going to happen.”

“However, there are some opportunities to narrow the gap, to get back to a place where we can coalesce around common facts, and then fight about that, as opposed to fighting about conspiracy and fantasy,” he adds. “It'll be an enormous challenge and a fascinating thing to watch politically.”

It’s clear that the insatiable curiosity that motivated the wide-eyed young Bostonian reporter is still very much alive and thriving in King. “The variety of what you get to touch in news has been the gift of my life,” he confirms. “And it's still a blast, to come to work every day, loving it.”

John King was nominated for Network Presenter of the Year at the RTS Television Journalism Awards 2021 alongside Victoria Derbyshire and Clive Myrie.