Saul Dibb helmed the acclaimed drama, BBC One’s harrowing true-crime serial The Sixth Commandment. The director moves between cinema, for which he has made the highly influential Bullet Boy and The Duchess, and TV shows, including The Salisbury Poisonings.

What does the job involve?

I guess the simple answer is that the clue is in the title: it’s about having a clear direction in which you want to take a project.

You’re the hand on the tiller, making sure all the departments and actors are going in the same direction.

I started in documentaries, so I’m trying to make things feel real and truthful. I’m not just trying to deliver the script, which is what a lot of people think a director’s job is. You have to breathe life into it so it doesn’t feel written, or even directed.

In some ways, I see my job as trying to subtly erase my own presence. I want people to be looking at [the actors] rather than me.

It sounds like a huge job?

It’s absolutely exhausting because there is no downtime. It can take pretty much a year to make a film or TV series.

Given that they take so long to make, are you picky about the films and series you take on?

You have to choose carefully. I’ve always wanted control over my projects and to make them in the way I wanted, whether they worked or not. To begin with, lots didn’t and I look back and say to myself: “My God, what was I thinking?”

What was your route into directing?

In my late teens, I got into photography. My dad made arts documentaries for the BBC, so we always had a Super 8 camera at home. I went to the University of East Anglia and did a theoretical film course; it was brilliant because I saw loads of films, but frustrating because I didn’t get to make them. I started making short films, but got diverted into making documentaries, which I loved and did for 10 years.

What was the first programme you directed?

New York to California, in 1995, a road trip from the village of New York in Lincolnshire to California on the north coast of Norfolk. I pitched it to Channel 4 and they put me together with the writer Jon Ronson and we went on this two-week, low-budget odyssey looking for the US in England.

I had a great champion in [producer] Peter Grimsdale – people who put their faith in you make a massive difference to your career. Afterwards, he commissioned Jon and me to make Tottenham Ayatollah, which was my first big success in documentaries.

Why did you turn to drama?

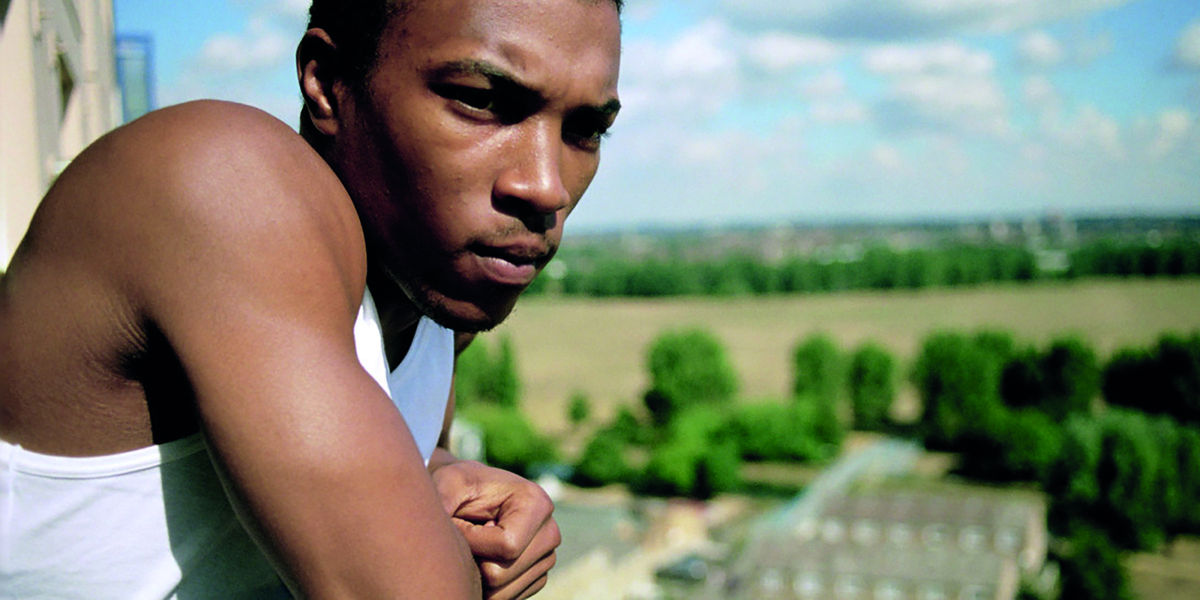

I wanted to explore the use of guns by young people in Britain, so I went to the BBC where David Thompson and Ruth Caleb were running a brilliant scheme with the Film Council to give documentary film-makers a chance to make low-budget feature films.

I pitched Bullet Boy, a bit flippantly, as “Kes with guns” as I wanted them to understand the sensibility of it – it wasn’t going to be sensational. I sent the script to Ashley Walters [he subsequently starred in the film], who was serving time in a young offender institution for carrying a gun. It came at the right time for him and me.

Film or television?

I don’t have a preference and I’m so glad that the snobbery that used to exist about working in TV has gone. It was just nonsense. Brilliant things exist in each form.

In TV, if you come on board as a director, there is a certainty that it will get made.

For a film, because they cost so much money and have to be sold around the world, often on the back of a famous actor, it’s much more precarious. I spent a year preparing a film that was four weeks away from production and then folded – and that’s not uncommon.

What do you bring to work with you?

Very little – a watch, because time is your enemy, and an iPad mini, which contains notes on the script, and mood boards.

What are the best and worst parts of the job?

Shooting an amazing scene: getting your actors together with a great script, such as Sarah Phelps’s script for The Sixth Commandment, and feeling that you’ve really got something special.

Then, once you’ve edited it, showing it to everyone involved and seeing them moved by it, that’s an extraordinary feeling.

The worst is when you’re unlucky enough to work with difficult people.

What attracted you to The Sixth Commandment?

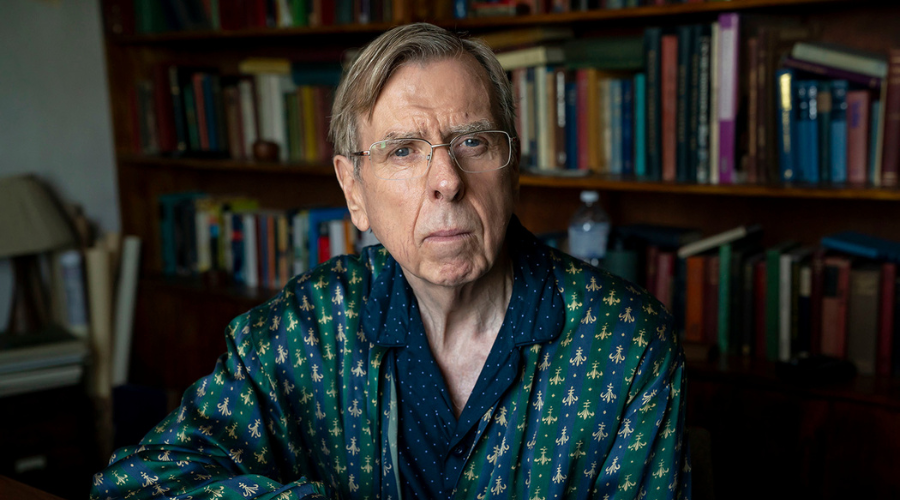

I knew the story, but I was blown away by the power of the script. The story of this lonely, closeted gay man in his sixties (played by Timothy Spall) who feels like he’s falling in love for the first time – I would have made that on its own – it was heartbreakingly told.

Its reception was extraordinary; it wasn’t just the fantastic reviews, it also connected with people from all walks of life across the country.

Are there any tricks of the trade you can share with us?

On set, I work really hard to create a sense of calm, which doesn’t mean I’m feeling calm myself. Everyone’s looking to the director – if the director is panicking, so will everyone else. No one does their best work under stress.

Has it ever got too stressful on set?

I made Suite Française with Harvey Weinstein as the producer, which was the most awful film-making experience of my life – he was a relentless bully. That was incredibly stressful.

After that, things don’t get to me in the same way – nothing will be as bad as that.

Which directors have inspired you?

The late, great Jean-Marc Vallée (Dallas Buyers Club and Wild) was a brilliant director. His films look amazing, but they also have a real sense of spontaneity and truthfulness.

What makes a good director?

The good ones are very clear about what they want to make and how they’re going to make it. They also need the ability to articulate their vision to everyone they’re working with and to bring them around so they share it. The good director also listens.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to direct?

Watch lots and lots of films and television – you can learn so much from seeing how others have told stories. You have to make things, as many short films as you can. And you need perseverance: you’ve got to be in it for the long haul.

Has the job changed over time?

The job hasn’t changed but, thankfully, film and TV set environments have. When I first started, I often didn’t like the atmosphere on set: the culture of it felt alien to me – they were monocultural and male. That’s not representative of the world we live in.

There have been big changes in the make-up of drama sets; they’re more inclusive and I see less bad behaviour. They’re still stressful environments, but they’re nicer places.

Are there genres you’d love to take on?

It’s never about the genre: it’s whether a project has a real emotional power that I feel I can bring something to.