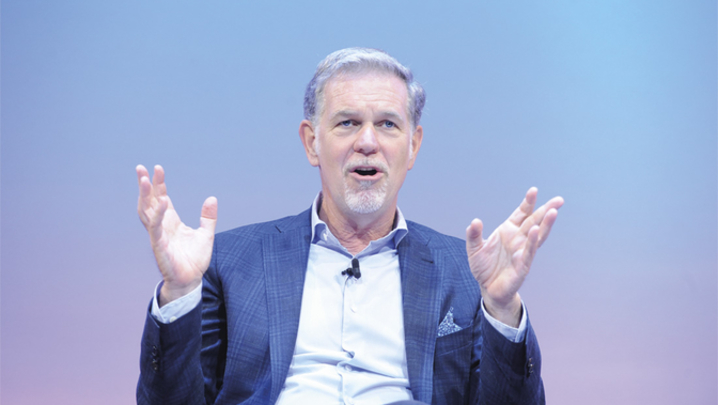

Simon Shaps reviews Reed Hastings’ new book – and divulges what happened when he was headhunted by the streaming giant.

Candour is a big deal for Netflix co-founder and co-CEO Reed Hastings. Having argued for “increased candour” early on in this eye-popping account of Netlix’s corporate culture, he returns to the idea some 60 pages later in a section called “Pump up candour”. Not content with that, he makes the point again, towards the end of the book, with the exhortation: “Max up candour” (Chapter 8).

So, in the spirit of pumping up my own candour, I should confess to a dalliance with Netflix. Back in 2014, I received a call from a headhunter asking if I was interested in a senior job at Netflix. A year earlier, the company had launched House of Cards, so Netflix already felt like the place to be in television.

I was given a job spec, which, to my eyes, contained nothing out of the ordinary other than that candidates were required to have mastery of PowerPoint (I certainly knew someone who could do that for me), Excel (I definitely knew what that was) and Word (bingo!).

I was invited to Paris for an interview, as the executive I would be working for was there for the launch of Netflix in France. This was before Netflix launched in 130 markets on a single day, a feat it pulled off early in 2016.

I then went to LA for a day of interviews, one every 30 minutes, with an assortment of people from across the organisation. Back in London, I spoke to the head of HR, who called me from somewhere deep in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Then nothing. I learned, once again, that silence is indeed the American way of saying no.

Reading this fascinating account of how Netflix does things differently, not merely in the way it has revolutionised television, but as the employer of 8,000 people around the world, I now realise, all these years later, that its business model and its corporate culture are different sides of the same story. The overused term “disruptive” does not do it justice.

During my day in the LA office, I had casually asked questions about holiday policy, and commissioning authority, which produced answers that made it abundantly clear that Netflix was different.

The company is not alone in seeking to recruit the brightest and the best, to achieve what Hastings calls “talent density”, shedding adequate performers as well as “jerks” along the way. Unlike others, it also believes in offering higher pay than its direct competitors. Once in place, these star hirings are left to make big bets.

These bets can be multi-million-dollar commitments. This was the case, for example, with documentary head Adam Del Deo’s decision to buy Icarus for $4.6m in January 2017. Apparently, his boss, chief content officer Ted Sarandos, simply told him to “swing big” if he thought it was going to be a hit. That was it. No business case or ROI analysis before the decision was taken.

‘The overused term “disruptive” does not do Netflix justice’

To Del Deo’s relief, the film eventually won an Oscar. Too many big bets that don’t deliver lead to a quick exit, or, as Hastings puts it: “Adequate performance gets a generous severance package.”

So, back to my question about holiday policy. I was told that Netflix had no rules around vacation. Instead it expected employees to use “good judgement” about the amount of leave they took. On the question of who needed to sign off major commissioning decisions, I was told that up 10 people across the organisation would weigh in.

My interpretation: nobody took any holiday because there was peer pressure to work long hours, with perhaps a couple hours off after lunch on Christmas Day. And on the signing off of new commissions, frankly, it sounded nightmarish. Who were these 10 people? Did they read scripts? How long did they take?

This book reveals I was wrong on both counts and I am sure my scepticism showed.

Netflix’s policy on holidays is designed to create a culture where employees are encouraged to “do what’s right for the organisation”. The “no vacation policy” is not a “no vacation” policy. On the contrary, top executives, from Hastings and Sarandos downwards, deliberately talk about their, often exotic, trips to “set the context” for everyone else.

With expenses, the same principle applies. There is no finely tuned expenses policy or approvals process. Employees are again expected to use their own judgement about what is necessary, and to “act in Netflix’s best interests”.

Around the time that the “no rules” rules were being introduced, David Wells, a senior finance executive, took his seat in economy on a short flight to Mexico, only to discover the entire Netflix content team sitting in first. Wells was surprised by the behaviour and the content team wondered why a senior executive was travelling economy.

The system is built on the notion that you need to give employees freedom to act, rather than exercising top-down control. In the case of the first-class tickets to Mexico, or lavish entertainment generally, individuals will nonetheless have to be prepared to justify the expense, and show how it was in the best interests of the organisation

to fly first or order six bottles of vintage claret. There may well be perfectly reasonable business arguments for both.

On the commissioning process, the “10 names” are not other people who might second guess Adam Del Deo’s intention to acquire Icarus and the unprecedented amount of money he proposed to spend. Instead, executives are encouraged to “farm for dissent” – seek out people who might challenge, or test out a decision – and “socialise the idea”, which means “taking the temperature” in the organisation about what is proposed.

The decision-maker is the person closest to the creative pitch and, as “the informed captain”, is encouraged to make the bet.

If it succeeds, Del Deo or anyone else is encouraged to celebrate the success (but perhaps not with vintage claret). If it fails, the onus is on the decision-maker to “sunshine” the decision. In Netflix language, that means talk openly about the thinking behind the decision and offer a detailed explanation for what went wrong and what has been learnt from the experience.

At the end of 2018, Sarandos was congratulated on the huge critical acclaim for Roma and the ratings success of Bird Box, which was viewed by a record 45 million subscribers in its first week. Sarandos’s response was that it wasn’t his decision to pick the two films. Instead, he explained, he picks the pickers, who, in turn, pick the films, in what he calls a “hierarchy of picking”.

After shadowing Hastings for a day, Sheryl Sandberg, the author and Facebook executive, told him: “The amazing thing was to sit with you all day long and see that you didn’t make one decision.”

Hastings and Sarandos hunt for talent, provide the essential context – what Netflix wants to achieve and how it operates – and then encourage their teams to take countless big swings. At the same time, they relentlessly seek out feedback on their own performance (some of it is quoted here and is not very pretty) and they make it their business to listen to feedback about employees across the company.

Netflix, in this account, is no easy ride. It is relentless in searching out great content, growing its worldwide subscriber base and further improving its technology. It rewards its employees well but, in return, it has sky-high expectations of them.