A one-day conference assessed the impact on participants of shows such as Benefits Street. Steve Clarke sifts the evidence

Who benefits from TV’s glut of poverty programmes? Is it the TV companies or the films’ protagonists? And what of the charities that are frequently involved in the making of this television sub-genre, which has been dubbed “poverty porn”?

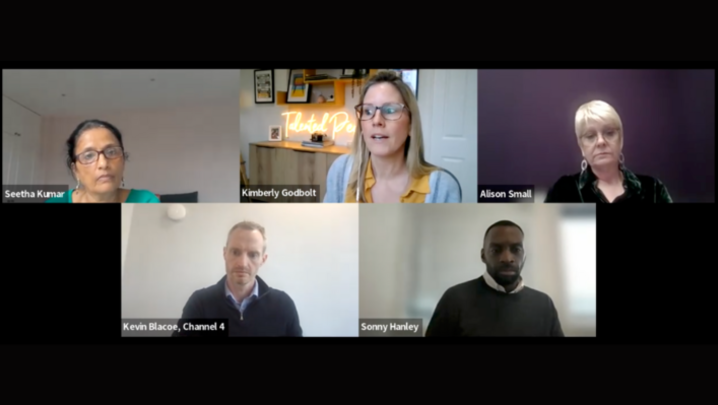

These were some of the questions discussed at a conference held at the end of November and organised by the RTS, BBC, Joseph Rowntree Foundation and National Council for Voluntary Organisations.

The setting for this wide-ranging, well-attended and timely debate was the Victorian gothic splendour of Manchester Town Hall. The building is no stranger to vigorous debate and “Who benefits? TV and poverty” did not disappoint.

Many of these programmes attract good ratings, although no single show has proved as popular as Benefits Street, which is seen as the genre’s pioneer. With an audience of up to 5.9 million, it became Channel 4’s most successful series of 2014.

At the conference, broadcasters and production companies were repeatedly advised by charities to avoid stereotyping those whose lives are blighted by poverty. They were urged to use responsible language and to treat contributors with respect and integrity. The very word “benefits”, it was noted, is widely associated with blatantly emotive terms such as “scroungers”.

However, sceptics were advised not to judge a programme solely by their lurid titles (two Channel 5 shows were called The Great Big Benefits Wedding and Benefits: Got Talent) or the opening 10 minutes. The message was: watch the show in its entirety before coming to a conclusion was.

There were attacks on shows in the vein of Benefits Street, not least from anti-poverty campaigner Steve Chalke. His charity, Oasis, now runs a school adjacent to Birmingham’s James Turner Street, where Benefits Street was filmed.

Chalke said that he regularly saw the impact that “shallow” TV shows and media coverage in general had on individuals struggling to make ends meet: “There is lots of great TV coverage, but, when things go wrong, they go really wrong,” he said.

He drew parallels between what he said were the worst of today’s TV poverty programmes and how, in previous centuries, people paid to watch “the freak show” at Bedlam.

Chalke suggested that more positive outcomes were likelier when people were given cameras and allowed to film themselves.

Ian Rumsey, Head of Topical at ITN, stressed the importance of allowing people depicted in programmes such as Channel 5’s Benefits (produced by ITN) to “speak for themselves”.

“We have a very strict set of protocols and we reject more people than those who end up in the programmes,” said Rumsey. “We look at how vulnerable they are, their mental health and other health issues [and] the impact on their children. We offer support before and after transmission.”

The founder of Oasis thought there was a fundamental problem: “When we speak for people who are poor, instead of allowing them to speak for themselves, we always patronise them.”

He added: “TV people have to maintain the right to edit their shows, but these people are disenfranchised. They are used to being spoken about and not being spoken to.…

“Producers should give these people their own voices.”

There was, however, praise from other charities for how TV covers poverty and related issues, including homelessness.

Daniel Flynn, who runs YMCA North Staffs, gave permission for BBC’s Panorama to film inside Stoke YMCA. The resulting documentary, Young, Homeless and Fighting Back, gained nothing but positive feedback locally and nationally, Flynn told delegates.

This was despite the hostility that Panorama encountered when its crew arrived at the YMCA. “This level of mistrust was not something I was expecting,” said Duncan Staff, who produced and directed the documentary. “There was enormous suspicion from everyone I came across.”

Chalke suggested that participants in certain shows examining the lives of poor people were often treated badly from the outset by programme teams.

They were not always asked to sign consent forms, he claimed.

This was not the experience of Daniela Neumann, Creative Director at Spun Gold TV. She described to delegates how one of her series, Through a Child’s Eyes, treated its contributors.

She highlighted an episode of the series, commissioned by Channel 5, that featured families living on low incomes. The children received high levels of psychological support during the production, she claimed.

“Before filming began, a psychologist visited the child and had a one-to-one session to ensure the child could cope,” Neumann said. “It was a very rigorous process.”

However, she conceded that, once the film was broadcast, it was impossible to prevent sensational coverage of the programme’s subjects.

She said: “We can control what we do in the edit but we can’t control what the tabloid press does. There is a whole machine that takes off.”

Tabloid sensationalism and social-media storms often go hand in hand with a certain type of poverty documentary.

But, as the Manchester conference made clear, these programmes are not one-size-fits-all. Behind the sometimes lurid titles, many different styles of TV are evident. The range encompasses reality soaps, empathetic human stories and considered, observational films that treat poverty seriously.

While it was agreed that society must avoid stereotyping those on benefits as scroungers, so, too, it was pointed out, critics of TV’s portrayal of poor people need to remember that most programme-makers are well intentioned. “No TV company sets out to damage people’s lives.… It is a good thing that we are talking about the issues surrounding poverty and benefits,” suggested ITN’s Rumsey.

“Broadcasters and producers have a responsibility to be truthful and to tell a story,” stressed Guy Davies, Channel 5’s Commissioning Editor, Factual.

“But this is not the same as always wanting to tell a story in positive terms…” he added. “I think we ought to be careful not to romanticise these issues and present films that are ceaselessly positive.”

One thing was clear. As David Bunker, Head of Projects at BBC Audiences, emphasised, programmes about poverty are “well watched”. They are particularly popular with young, less-well-off women, according to the corporation’s research.

A crucial question was how TV audiences respond to poverty shows. Almost a quarter of viewers (24%) said that watching them made no difference to their attitude to poor people.

Worryingly, there are indications that viewers’ empathy decreases. While less than a fifth of the sample (18%) said they felt more sympathetic after watching a programme depicting poverty, 23% said they became less sympathetic.

However, Bunker said it was wrong to say that audiences were unmoved by shows such as Benefits Street.

“The response varies across different titles,” he said. “It was clear from the responses we looked at to individual programmes. They do trigger a range of emotional responses on a regular basis – pity, anger, sympathy, contempt, understanding.”

Perhaps the last word should go to The Times TV critic, and Television contributor, Andrew Billen. During one of the conference panel discussions, Billen said that broadcasters “must never, ever give away their editorial control to charities”.

He added: “Much as I admire the work done in this room, I never want programmes to be made by the charities about the charities.”

‘Who benefits? TV and poverty’ was held at Manchester Town Hall on 30 November. The event was chaired by Louise Minchin. To watch video highlights, go to www.bbc.co.uk/responsibility/tvpoverty-conference