Steve Clarke and Matthew Bell distil two days of expert advice from leading television practitioners

Journalism

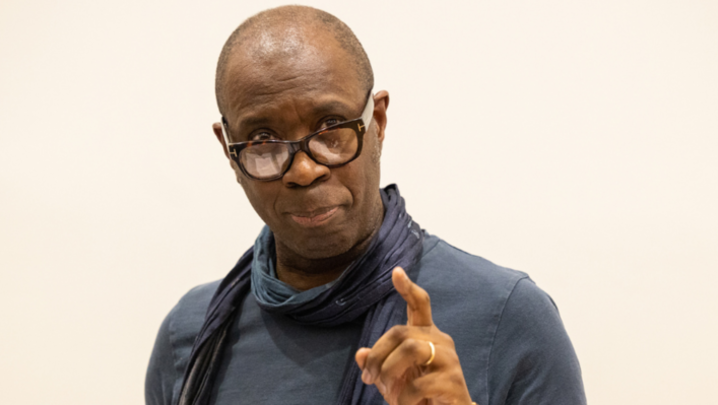

Clive Myrie

Journalist and presenter, BBC News

In an era of widespread concern about fake news, trusted and experienced correspondents such as the BBC’s award-winning Clive Myrie are more important than ever.

He told the RTS how, during his career of 30-plus years, he had reported from many of the world’s trouble spots, latterly Myanmar and Yemen.

BBC News is respected internationally for its high standards of accuracy and impartiality but this did not mean, said Myrie, that reporters should put a clamp on their own emotions.

“If you’re feeling something, bring it out,” he advised. “Don’t let it overwhelm or dominate the story, but I don’t like to see news reporters or presenters who are robots. You’re a human being as well as a reporter. If you’re reporting from a war zone and see a dead baby in front of you, I’d be surprised if you’re not showing some emotion.

“Let your emotion inform the story. The great reporters are able to translate a story for the viewer through their own experience.”

The son of Jamaican immigrants, Myrie read law at the University of Sussex. There, he started doing journalistic work for the local radio station.

As a child, he’d been inspired to consider a career as a globe-trotting foreign correspondent by watching TV.

The late Alan Whicker, a fixture on TV schedules from the 1960s to the 2000s, and, especially, Trevor McDonald were early role models.

“I’m a Northerner [he was brought up in Bolton] and didn’t come from a media family… There was a guy on ITV who looked like me and sounded a bit like me. He travelled around a lot. I thought maybe I could do what he did. He was Trevor McDonald.”

After graduating, he was accepted as a trainee barrister at Middle Temple. At the same time, he also applied to the BBC. “I chose the BBC and my parents have never forgiven me,” he recalled to laughter from the RTS audience.

Moving from BBC Radio Bristol to TV news in London required dedication and working unsocial hours.

A week’s work in the West Country would be followed by a drive up the M4 to do weekend shifts in the capital for BBC TV News.

Eventually, Myrie gained a reputation as a foreign correspondent for reporting from places such as Liberia in 1995, where reporters experienced difficulty gaining access.

Asked what personal qualities were necessary for this sort of journalism, he replied that empathy was vital: “The most important thing is to try and put yourself in someone else’s shoes and tell their story as honestly as possible. It’s not about you, the reporter, it’s about them.”

Factual entertainment

Nav Raman

Founder and creative director, Chatterbox

Collaboration is key to being a successful producer of such hit shows as Child Genius, Brat Camp, The Unteachables and Bollywood Star, all commissioned by Nav Raman when she worked at Channel 4.

Today, she co-runs the new indie Chatterbox, where she hopes to extend her winning form in factual entertainment formats.

Raman emphasised that programme ideas are unlikely to arrive fully formed and therefore need to be worked on by groups of people. “No one wakes up with a fully-formed idea,” she told the RTS students. “If you have the seed of an idea, you need to be able to explain it simply, in order to get someone else to understand it quickly.

“Keep asking yourself, what is it? It can go on for ages as the idea is refined and distilled. Hopefully, you, as a producer, do that with a broadcaster.”

With many different content platforms operating across streaming, terrestrial and multichannel networks, it’s absolutely vital to consider the intended audience when honing an idea.

She said: “Look at the platform or broadcaster you’re thinking of pitching to and make sure that it is not already doing something similar to your idea.

“Ask yourself if the tone, sensibility and attitude chimes with a particular channel. Where will this idea sit –‘You do this kind of show so you really need this kind of show, because it will add to what you’re trying to do.’”

Keeping an idea simple was essential: “Simplicity is the key. When I was commissioning, if I didn’t know what the show was in two or three lines, I’d tell the producer to rethink it.

“I’d sometimes get a beautifully presented five-page document and get to the end of it and think ‘So, what’s the show?’”

She added: “For me, the other big thing is purpose – what’s the point? Just because you can do it with TV cameras doesn’t mean that it’s a TV show. You should be trying to answer a question.

“At Channel 4, I commissioned The Unteachables, which tapped into kids who were excluded from the state education system. My question was: ‘Is there such a thing as an unteachable kid?’ My answer was ‘No’.”

Drama

Sophie Petzal

Writer

Sophie Petzal’s first original TV series, Blood, has recently aired to critical acclaim on Virgin Media One in Ireland and Channel 5 in the UK.

Having been accepted on to the BBC’s Production Trainee Scheme, Petzal worked as a script editor on CBBC dramas, which, she argued, was “an invaluable way to learn about television production and writing”.

She went on to write scripts for CBBC shows, including Wolfblood, The Dumping Ground and Danger Mouse. “If you can turn stuff in on time, you tend to get dragged from one show to the next,” she said.

Getting a break as a new writer, admitted Petzal, was “undeniably tricky” but “children’s drama is a really good place to start”.

In fact, she told the students in the audience, “Production jobs of any kind are never a waste of your time because the relationships that you’ll make are invaluable. It’s only in the last couple of years that I’ve received offers for things from people who’ve never met me.”

Petzal graduated to writing episodes for ITV’s Jekyll and Hyde and BBC Two’s medieval drama The Last Kingdom. Writing the latter, she said, was a “great experience”, and described the episodes as “like hour-long plays, beautiful, textured, emotional pieces of writing”.

Adding another string to her bow, she took on a last-minute rewrite for the Sky Atlantic thriller Riviera: “These jobs are nice because, if you do relatively well, everyone thinks that you’ve saved the day; if you do terribly, people tell you that it was doomed anyway.”

Writing Blood, which stars Adrian Dunbar as an Irish country GP who is suspected of murdering his wife, was “massively exposing”, said Petzal. “But it was an incredible experience and I’m deeply proud of it.”

Documentary

Brian Woods

Founder, True Vision

Katie Rice

Producer/director

For more than two decades, True Vision has built a reputation for making hard-hitting films that address important subjects – and, thanks to the power of television, make a difference.

“You see some really interesting films at [documentary] festivals, which probably 10,000 people will see in the life of a film,” said the indie’s founder, Brian Woods. “They’re not going to have an impact on the world unless a broadcaster picks them up and shows them.”

It is not always a comfortable experience making docs such as True Vision’s multi-award-winning film about Aids orphans in South Africa, The Orphans of Nkandla.

“The temptation is to intervene but, if you intervene, then you change the reality,” argued Woods. “You have to let the reality play out because, if you don’t let things happen and get them in the can, then you don’t have the film that has the power to affect things, not just for these children but for hundreds of thousands of children across Africa.”

Nevertheless, film-makers have a responsibility to look after their contributors, continued Woods: “You form a relationship with them. It’s not friendship, because you are making a film about them… but you want to keep in touch [and] keep supporting them if you can.”

True Vision’s Katie Rice, who directed Child of Mine, a Channel 4 series examining couples affected by stillbirth, reiterated the importance of the bond between film-maker and subject: “All our films are based on really strong relationships with contributors. If they want us to stop [filming], we stop. It’s not our story – it’s theirs.”

Woods identified “sheer, bloody-minded perseverance” as the most important attribute needed to make it in TV. He recalled that he wrote “about 150 letters” before he landed his first job in TV as a researcher.

On selling an idea for a documentary, he recommended making a taster tape: “Do it on your phone – it doesn’t have to be shot on a £20,000 camera, because [commissioners] are interested in the characters and story you’ve got.”

Clive Myrie was interviewed by Naomi Goldsmith, media consultant and journalism trainer. Nav Raman was interviewed by Sharon Powers, creative director, Potato. Brian Woods and Katie Rice were interviewed by Alex Graham, joint CEO, Two Cities Television. And Sophie Petzal was interviewed by John Yorke, a drama producer whose credits include Wolf Hall, Life on Mars, The Street and Bodies. The producer was Helen Scott.

Sound

Phil Bax

Sound recordist

Greg Gettens

Head of broadcast factual sound, Molinare

Together, they covered the two ends of the sound spectrum. “Phil records the sound on location,” explained Greg Gettens. “We add music, effects and sound design to produce the final mix you hear on telly.” Recently, he added “explosions and bullets whizzing around people’s heads” to BBC One’s D-Day’s Last Heroes: In Their Own Words.

Bax experienced the high life on BBC One’s Supersized Earth, working at the top of the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, to capture the sound of fear in presenter Dallas Campbell’s voice as he swayed in the wind, cleaning the skyscraper’s windows.

Specialist recordists are threatened by the increasing use of single sound/camera operators. “If you’ve got a person dedicated to each [part of the filming process], you’re going to get a better result,” argued Bax. But, added Gettens: “If [you are] in a confined space with only room for one person with a camera and microphone, that’s what you have to work with.” And, he added, “budget limitations” often militate against hiring a sound specialist.

Hitting the right note is the key to working in sound. “Over the past 15 or so years, I’ve worked on all sorts of documentary projects, but with a small cohort of the same directors, production managers and camera people. If you work together once and get on well, you work together again,” said Bax.

Gettens agreed that being personable is part of the sound mix: “A lot of the time, I’m in a dark room for 10 hours a day, five days a week with other editors – they have to get on with you. It’s not all about sounds; a lot of it is about personality.”

And, added Bax, try everything: “The [BBC] put me on a gantry at a football match with a bit of rusty old equipment that didn’t work and a commentator who berated me all afternoon. I realised I didn’t want to do football matches. [But] use opportunities rather than dismissing them outright – then you find out what you want to do”.

Camerawork

Phil Mash

Director of photography

Geraint Warrington

Director of photography

Two leading directors of photography (DoPs) offered some useful pointers to the many students in the audience with their hearts set on a career behind the camera.

Mash admitted that he was “rubbish at the technical side” when he started out. He recommended stills photography as a good way to practise: “Filming is effectively a series of still frames – composition is everything.”

Smartphones, said Geraint Warrington, “are great for trying out composition – but that’s it. They don’t teach you how to create a look on a normal camera. [You don’t] learn the full skills of photography – I’m a great believer in [learning] on a proper camera.” To practise, added Mash, “a DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) camera is the place to start”.

Mash argued that cameras can “be good or bad, depending on who’s got hold of them. [But] the lenses on the front of the camera make a huge difference.”

Warrington agreed with his fellow DoP: “Try to use the most expensive lens you can afford. I mainly shoot on the Sony F55 – it’s an amazing quality camera. It’s also quite lightweight – 90% of the stuff I do is [with the camera] on the shoulders.”

Studying for qualifications gives the would-be DoP the opportunity to get to grip with cameras and to “gain the technical knowledge on how cameras and lenses work”, said Warrington, who studied at [media and design university] Ravensbourne. But, added Mash, while “qualifications are great, you will still have to work your way up – there’s nothing like experience”.

How to get that experience? Contact camera companies, suggested Warrington: “You’ll be prepping the kit to go out on shoots, so you’ll have all this equipment in front of you to learn [from] – you could be a very useful camera [assistant] if you know how the equipment works.”

Editing

Rick Barker

Editor

Pia Di Ciaula

Editor

Although they worked in different genres – factual and drama respectively – both editors agreed that their jobs required total dedication.

“I am very passionate and work long hours,” said Pai Di Ciaula, whose recent credits include A Very English Scandal, starring Hugh Grant as Jeremy Thorpe. She was recently nominated for an RTS Craft & Design Award for the series.

Di Ciaula also edited Netflix’s The Crown, working with director Stephen Daldry. “He likes to shoot a lot of material and expects me to send him assemblies at the end of every day.

“I would get somewhere between two and a half to six hours of material every day. They couldn’t be rough assemblies. They had to be tight and have a soundtrack. He doesn’t like looking at green screens. My assistant had to composite all those shots, so it looked like a finessed show even though it was a first assembly.”

Rick Barker, whose credits include Who Do You Think You Are? and Long Lost Family, said: “I think it’s fair to say that editing can be fairly intense.

“Certainly, the current-affairs stuff that I’ve done, you find yourself in the edit suite occasionally having discussions at very late hours of the night over whether a scene is working – or if a producer or a journalist can write a very long piece of expository journalism over your beautifully crafted sequence.”

In drama, Di Ciaula told the students that the work of an editor involves pleasing the director. “Directors are kind of possessive of the editing,” she revealed. “Sometimes, they allow producers to watch assemblies, but they don’t want any comments because they want to avoid being biased by comments made early on in the process.”

For factual shows, it’s the editor who sets the agenda in the edit suite, noted Barker: “I think it’s important that the edit suite is the editor’s. We don’t have that layering that people who work in drama do. In factual, you’re there to bring a fresh pair of eyes. Your job is to try and find the story within the rushes.”

He added: “Part of what I do as an editor is manipulating emotions. In factual TV, we have long debates about how far you can go and how one is able to manipulate the truth.

“The reality is that everything we do is artifice. We create interviews, we chop up sentences and we make films.”

The sound masterclass was chaired by Emma Wakefield, MD of Lambent Productions; the camerawork session by Helen Scott; and the editing masterclass by Ruth Pitt, creative director of Under the Moon. The producer was Helen Scott.