The BBC Chair sees impartial news as a vaccine to beat an epidemic of dangerous disinformation.

In an age driven by social media, where, “for most people, affirmation is more satisfying than information”, the BBC’s ability to provide free access to accurate, impartial news is essential to combating the harmful effects of fake news.

That was the core of ex-Goldman Sachs banker Richard Sharp’s argument in favour of impartial public service news as he gave his first RTS speech as BBC Chair since being appointed in February.

“If disinformation is the disease running through our societies, impartial news can be the vaccine,” he added. His elegant, erudite address was enlivened by literary references to Milton, Swift and Orwell, whose statue by the British sculptor Martin Jennings stands outside Broadcasting House.

Sharp said the Orwell quote on the wall beside the work of art encapsulated the BBC’s commitment to information over affirmation: “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear”.

Reporting without fear or favour is fundamental to the reach, trust and respect the BBC enjoys in the UK and overseas. This is why the BBC Board and the Director-General, Tim Davie, “have identified impartiality as our first priority”.

“Impartiality, candidly, is a prerequisite for the existence of the BBC. And it must be seen as a journey not a destination – something we must prove again every day,” insisted the Chair, looking fit and tanned in shirtsleeves.

He continued: “Getting this right is about more than safeguarding the future of a cherished institution that continues to have a critical role to play at the heart of British national life.

“It also offers the BBC a chance to define itself globally as a pre-eminent purveyor of facts in the disinformation age. At a time when news provision has become a key weapon in the battle for global influence, the BBC World Service has historically been one of the jewels in the UK’s crown.

“Our opportunity in the digital age is bigger than ever to deliver information across the globe as a good in itself, and as an opportunity to drive UK values of democracy, freedom and the rule of law worldwide.”

Covid showed that the dangers of disinformation had never been clearer – and, as the BBC had demonstrated, the demand for high-quality information had never been higher.

“UK audiences in their millions have turned to traditional sources for news they can trust,” Sharp said. “Fact checking services have been critical in helping to debunk dangerous myths.

“And many platforms are now collaborating closely with trusted news brands such as ours to flag up falsehoods in real time.”

He added: “The presence of impartial sources in our daily news diet will become increasingly valuable.… News that is independent of commercial or political interest… that has an obligation to consider events from all sides and offer the context and analysis [will] help audiences make up their own minds.”

There were urgent questions to be answered about the future media world we want to live in: “We need to rethink the regulatory environment in this country – and replace a Communications Act that pre-dates Facebook with one that can deliver on a clear vision.

“But we also need to look at where the digital world comes up against the fundamental rights, freedoms and privacies we sign up to as societies and individuals.

“Does the principle of media freedom need to be redefined and re-enshrined for the digital age?

“Do we need to claim our personal data as a human right, rather than an asset to be bought and sold?

“Now is the time to put in place the rights, protections and education that will safeguard – not just our media environment – but the stability of our societies and democracies long into the future.”

‘We should cherish the BBC as a competitive advantage for the nation’

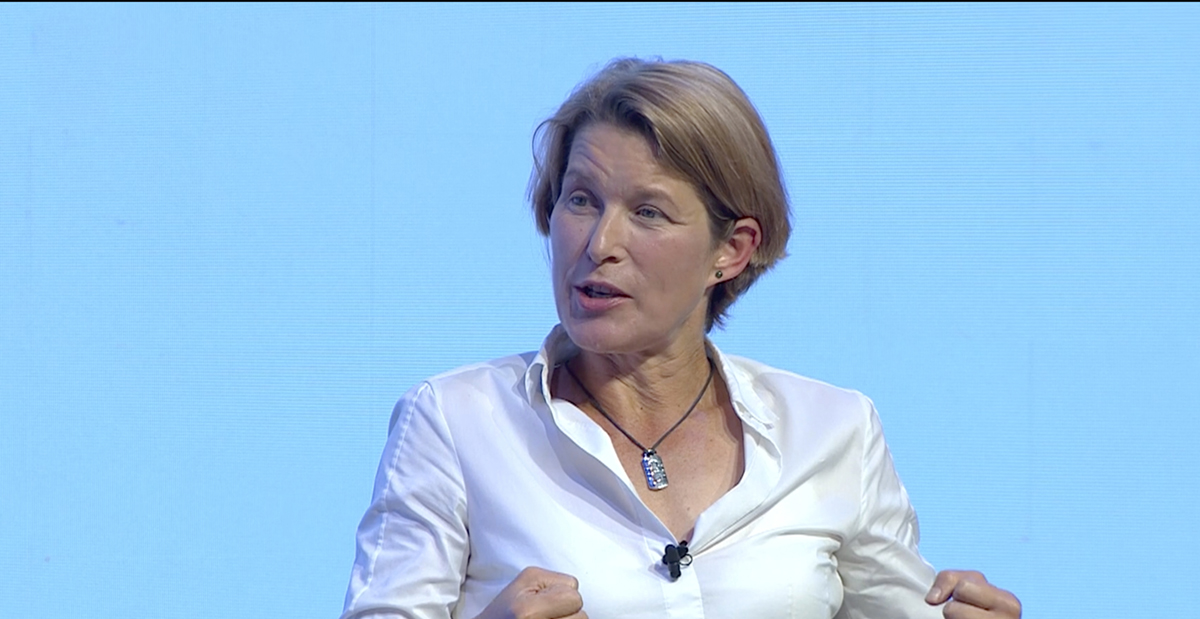

Following his speech, Sharp was questioned by the former Newsnight journalist Stephanie Flanders, now Bloomberg’s senior executive editor for economics. She noted that he hadn’t mentioned the licence fee. This led Sharp to point out that the BBC cost licence-fee payers a mere 44p a day per household.

This represented “fantastic value” for a service spanning TV, radio, websites, the World Service, children’s, iPlayer, Sounds “and a morning argument with your radio”. Moreover: “The BBC contributes to fighting media poverty. There’s so much money in the system because of what people pay for Sky, Netflix and Amazon Prime.

“There needs to be a national utility that delivers insight, education, children’s and these other assets at a price people can afford – and we can do so because it’s imposed.

“For individuals and the world, I happen to think it’s a good thing. The question is: does the Government think that too?... We should cherish the BBC as a competitive advantage for the nation as a whole.”

How much would he worry if the next licence-fee settlement was below the rate of inflation? “There’d be a hole in my budget. Media inflation is running at about 9%. It is an issue. Tim [Davie] and his team have taken enormous cost out of the BBC already. The low-hanging fruit has gone. There would be serious consequences to a poorly funded BBC.”

On the question of the BBC’s independence from government, how possible was it to maintain this when we’ve been told that every time BBC officials visited the last culture secretary, he began the meeting by reminding them that the Government enjoyed an 80-seat majority, probed Flanders.

“It goes to: ‘Do we have integrity as an organisation?’ If you give up your integrity, you don’t have a right to exist. I’m very proud of the fact that, on the day I was having a discussion with the Prime Minster, Laura Kuenssberg broadcast her interview with Dominic Cummings.

“We take our editorial decisions independently and manage the editorial process objectively.”

While both Sky’s CEO, Dana Strong, and ITV’s CEO, Carolyn McCall, sidestepped questions regarding Channel 4’s possible privatisation, the BBC Chair was more forthcoming as he appeared to endorse selling the broadcaster.

Sharp said: “Channel 4 was developed to bring a differentiated voice at a time when we didn’t have that open access to all the different voices that we have now. It [privatisation] is a little local issue – this group [the industry leaders attending Cambridge] should be concerned about Britain’s place in the world as an industry that should be strong globally. Who owns Channel 4 will fit into the strategy of one of the big players, or not.”

He continued: “In a world that is moving so quickly off linear, that is timestamped in terms of its presence, it doesn’t mean that [Channel 4] can’t make a lot of money from advertising, but I can certainly understand why it may need to now fit in with the strategies of some of the other players.”

Sharp added: “There will be a consequence of Channel 4 being privatised but that is part of some of the bigger trends which are more consequential to the BBC than this.”

Finally, in the context of impartiality, would the Chair want Andrew Neil back at the BBC? “I enjoy watching him. Whether he fits into the BBC is a matter for Tim Davie.”

Session Five: ‘UK keynote: Richard Sharp’. The BBC Chair was interviewed by Bloomberg’s Stephanie Flanders. The session was produced by Sue Robertson and Martin Stott. Report by Steve Clarke.