The scythes, sex and sunsets fired viewers’ imaginations. Steve Clarke hears from an RTS panel how Poldark was rebooted

Reviving a much-loved drama series from a less competitive and less knowing TV era was never going to be easy. But everything fell into place for the team that resurrected the swashbuckling period romance Poldark, originally a big hit for BBC One in the mid-1970s.

Even the notoriously unpredictable Cornish weather played ball – and the show went on to spark a media sensation when the rebooted Ross Poldark took his top off.

Forty thousand Radio Times readers voted Poldark – played by the ridiculously buff Aidan Turner – scything shirtless as last year’s best TV moment.

Perhaps more to the point, the eight-part revival gave BBC One another Sunday-night hit drama and helped the channel to reaffirm its dominance over ITV.

It might have been a very different story, according to those who made the show, when they spoke last month at the latest RTS “Anatomy of a hit” session.

“Generally, remaking an old series is not a good thing,” admitted Damien Timmer, Managing Director of Poldark producer Mammoth Screen, famous for such other costume productions as Wuthering Heights and the keenly anticipated Victoria. “Just because Poldark was a success first time around would not be a reason to do it again,” he added.

Why, then, did Mammoth decide to risk all and revive one of the BBC’s defining TV shows of the terrestrial era, probed the evening’s chair, Boyd Hilton. It was not as if today’s TV schedules were light on either serial or period drama.

“Every six months, I said in one of our regular development meetings that ‘we should do a big, sweeping romantic Cornish saga such as Poldark’,” Timmer remembered.

At the time, he had not seen the original BBC series (watched by around 15 million viewers) because he wasn’t old enough and hadn’t read any of Winston Graham’s dozen Poldark novels.

Still, he had a strong sense of the stories’ ingredients: crashing waves, sea fogs, smuggling and misty moors.

He must have also reckoned on the appeal of a cracking good love story set against a melodramatic background of costume-clad skulduggery and intrigue.

The next time that Timmer mentioned his notion of doing a show akin to Poldark, instead of the usual blank looks from his staff, one of them, Producer Karen Thrussell, said “Why don’t we just do Poldark?”

“She’d never watched the TV series: Karen was too young. But, as a girl, she’d read every single novel and fallen in love with Ross Poldark in a really big way,” the Mammoth Managing Director explained. As things turned out, she wouldn’t be the only one to have a crush on Ross.

Despite his colleague’s infatuation, Timmer told the RTS that he still had mixed feelings over a Poldark reboot – though, by then, Mammoth had splashed cash on the rights.

He approached playwright and screenwriter Debbie Horsfield. She was an unusual choice to pen a script for a period drama based on someone else’s stories.

“I remember people saying, ‘Oh, it’s a bodice ripper.’ And I thought: ‘Is it? How do you define bodice ripper?’

Her forte is contemporary family fare, often set in the industrial North of England, rather than the windswept moors of the South West; Horsfield is a native of Manchester and so, coincidentally, was Winston Graham.

Never before had the writer adapted someone else’s words; Horsfield always works on her own projects. These have included the influential BBC One series Cutting It. The show focused on the lives and loves of a group of Mancunian hairdressers. Cutting It ran for four series and was nominated for both RTS and Bafta awards.

So why did Horsfield make an exception for Poldark? “It came at a time when I was asking myself why has nobody ever asked me to do an adaptation? They think I only write contemporary, Northern-based family drama.”

Devouring the first two Poldark books on holiday, she was quickly smitten by the power of Graham’s storytelling.

Not that the ingredients of a gripping page-turner always match the essential elements of an episodic, peak-time TV drama. “I remember writing the first line of dialogue that is not in the book and feeling incredibly nervous,” said the screenwriter. “I asked myself: ‘Do I have the right to do this?’”

The fact that Graham’s tales are “epic and domestic” appealed to her: “It’s epic in the sweep of storytelling and the geography, the landscape and its heightened passions, but actually ordinary and domestic, detailed and, hopefully, identifiable with.

“That’s what I love when I watch it. I look at those landscapes and yet I look at those little scenes where two people are arguing in a room. That’s real life set in a gorgeous landscape.”

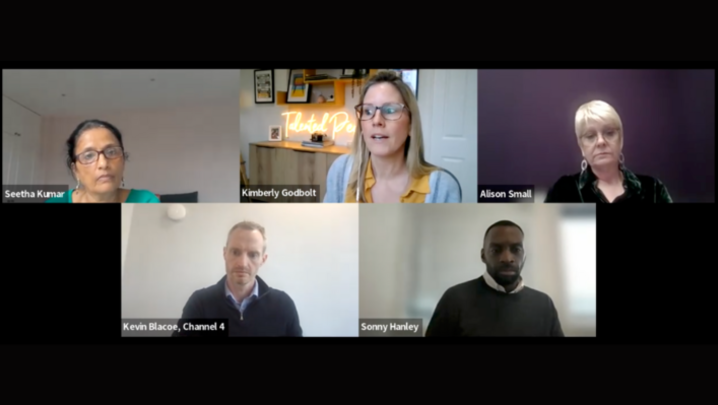

Anne Dudley, and Damien Timmer (credit: Paul Hampartsoumian)

Horsfield’s scripts aside, the key to Poldark’s unusual success was casting Aidan Turner as the central character.

Both Horsfield and Timmer had the actor in mind for the part of Ross Poldark – although neither had told the other. “One day, Damien and I were driving over Bodmin Moor in the fog. He asked me who should play Poldark,” recalled Horsfield. “He muttered that he’d thought of Aidan. I said: ‘Oh my God, that’s who I think should play Ross, too.’ That’s never happened to me before.”

Horsfield had enjoyed seeing Turner in BBC Two’s Desperate Romantics and BBC Three’s Being Human. Having, by this time, written a lot of the Poldark scripts, she’d concluded that the actor’s style suited the Ross character.

“In both Desperate Romantics and Being Human, Aidan played an outsider,” she explained. “Ross is very much an outsider, too. He’s rebellious and reckless.

“Also, Aidan is very charismatic but has vulnerability. He is charming and lights up the screen.”

Timmer said that getting him to agree to play Poldark was straightforward. He had recently finished The Hobbit and was scouting for a big, meaty part.

“The thing about Poldark is, if you haven’t got the right Poldark, there is no point in making it. You have to have someone in your head who you think is up to it,” emphasised the man from Mammoth. “Aidan completely made it his own.”

“You write in the script, ‘breathtaking sunset’, but you never think you’re actually going to get it. But it was one breathtaking sunset after another,”

Thanks to the series-defining scene of Poldark, naked from the waist up, engaged in some pre-industrialisation agricultural work (see box, right) the re-versioned show rapidly consolidated a loyal fan base.

Inevitably, the tabloids made much of the show’s supposed raunchiness. But Horsfield denies her version of Poldark is a “bodice ripper”.

“I remember people saying, ‘Oh, it’s a bodice ripper.’ And I thought: ‘Is it? How do you define bodice ripper?’ Is it a bodice ripper when no bodices are actually ripped? There is a moment when Ross’s hand goes into Demelza’s dress…

“You see a couple of scenes in the bedroom, where Ross has no top on. That’s about as raunchy as it gets. There are no full-blown sex scenes.… To be honest, I think it is quite subtly done.”

To prove her point, the RTS audience was shown a clip of Ross romancing Demelza. It is the scene (taken from the novel) in which he slowly unfastens the back of her gown and then begins to caress her naked back.

Horsfield said the sequence involved writing “one of the most detailed pieces of stage directions” she had ever scripted. It needed to be “highly charged and erotic, but we didn’t need to see very much. It was all in the detail.”

Costume Designer Marianne Agertoft tried to ban the scene – not for reasons of propriety but because 18th-century English dresses fastened from the front. “Marianne said: ‘I can’t do a dress that opens down the back’,” recalled Horsfield. “There was a lot of toing and froing. I said: ‘I totally get it, but in this instance the story trumps historical accuracy.’ Marianne then made this beautiful dress – which laces up at the back.”

Much of the original Poldark was filmed in the studio. Mammoth’s revival needed to embrace higher production values because audiences’ expectations of TV drama are now so much higher.

There is the Cornish landscape at its shimmering summer best. “You write in the script, ‘breathtaking sunset’, but you never think you’re actually going to get it. But it was one breathtaking sunset after another,” said Horsfield.

Interior and exterior scenes were shot at several West Country historic sites to help create an 18th-century vibe. These included Chavenage House in Gloucestershire and the Georgian streets of Corsham in Wiltshire.

The approach to the narrative was strictly 21st-century, however.

“The requirements of storytelling today are rather different to what they were in the 1970s,” explained Horsfield, who has adapted all 10 episodes of Season 2, which is expected to air this autumn. “It is required that you set out your stall and get your story rolling within the first page. Blame the remote control and 9 million channels for that.

“That is the reality. That’s what you’re working with. I am not complaining but, nowadays, you do tell stories in a different way.”

One factor that remains unchanged from the time when Poldark made its small-screen debut is the importance of working together as a team.

With this in mind, Horsfield made a point of always making herself available to the cast, by phone or via email, during filming. This enabled her to answer any script-related questions.

“What you realise is that the process is entirely collaborative. You cannot start thinking, ‘Oh my God, it’s all about me’,” she told the audience. “It’s not all about anyone, it’s all about all of us together. If we don’t all collaborate, we don’t actually have an end product.”

‘Poldark: Anatomy of a hit’ was held at One Great George Street, central London, on 14 April. The producers were Sally Doganis and Barney Hooper.

Britain catches chest fever

‘Who’d thought that one photograph [the picture of a topless Poldark scything in a Cornish field] would go global and there wouldn’t be a day in six months when it wasn’t in the paper,’ said screenwriter Debbie Horsfield. ‘Normally, after a show has had its first episode, you’re kind of begging the press to show a bit of interest.

‘There wasn’t a day when there weren’t four or five articles in the papers. It was wonderful.’ Horsfield revealed that she had written the scything scene before Aidan Turner was cast as Ross.

‘It said in the script that he’s scything, he’s sweating and it’s a hot day. It’s taking place from Demelza’s (Ross’s future wife) point of view.

‘It’s the day after they’ve had sex for the first time. The script is very clear. She’s looking at him thinking “Oh my God, what did I do? What’s going to happen now? Where do we go from here?’’

‘I don’t think any of us thought: “Wow, that’s going to be in every newspaper for the next year.’’’

Mammoth MD Damien Timmer said he remembered watching the rushes of the scything sequence and it being ‘scary how naive I was’ about the impact they would have.

As for Season 2, Horsfield said that there would be no more topless outdoor scenes. The series was shot in Cornwall in the autumn when it was too cold to have anyone take their shirt off.

But event chair Boyd Hilton said that he had spoken to Turner, who had told him that some of the scenes in the second series were ‘going to cause a stir’.

Farthing's fun: playing a villain

Jack Farthing, who played George Warleggan: ‘I initially auditioned for Francis Poldark (Ross’s cousin). [At the time] I thought that I was much more suited to that role. But now I feel completely connected to George. I feel like I am as horrible as he is [laughter from the audience].

‘It’s fun to play a villain. The most fun thing is that he feels real.… George is only effective if you can believe in him. If you don’t, he just becomes a psychopath and you distance yourself from him.

‘I can justify everything that he does. You can understand why he behaves the way he does…his chips, his resentments and his vulnerabilities.

‘As an actor, that’s all you can ask for, so that you can find a way into the part.’

The classic art of scoring Poldark

The Oscar-winning composer Anne Dudley wrote the music for Poldark. Many critics praised her score. Variety said it had ‘haunting and wonderfully romantic’ qualities.

Dudley told the RTS that composers come on board much later than the rest of the team. ‘You can’t start work until the film is edited,’ she said. ‘Generally, I’m working with a final cut.’

Screenwriter Debbie Horsfield wanted something similar to Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis: ‘I liked the lush romanticism of it but also the grittiness of the solo strings.’

‘All through Poldark, there’s a contrast between the solo violin played in a folk style without very much vibrato – very hard and uncompromising – and the orchestra,’ Dudley explained.

She added: ‘The violin represents the character of Ross Poldark who is at odds with his surroundings and his background.

‘He is born into the gentry but he identifies with the common people. He is always dissatisfied with what’s going on. The violin stands out against the orchestra. That was my starting point. I then did a little research.’

Dudley listened to Cornish folk songs. She found their ‘rather modal style of English pastoral music’ inspiring. So the composer set out to invent ‘a world of music that is part of the Cornish tradition’.

She was determined that the title sequence should contain a proper theme. ‘That’s something you don’t always see on TV these days,’ regretted Dudley. ‘I wanted the title sequence to reflect the imagery of crashing waves and passion, something that takes you into that world. I tried to represent that with the piano. The theme is played on the violin in folk style. That is then taken over by the orchestra but the violin has the last word.’

She wrote on piano before making a demo, which key members of the production assessed.

Once this was approved, the orchestrations were written. Dudley then oversaw the studio recording.

‘The aim was to hide the music from the viewer while heightening the emotional content,’ she said.