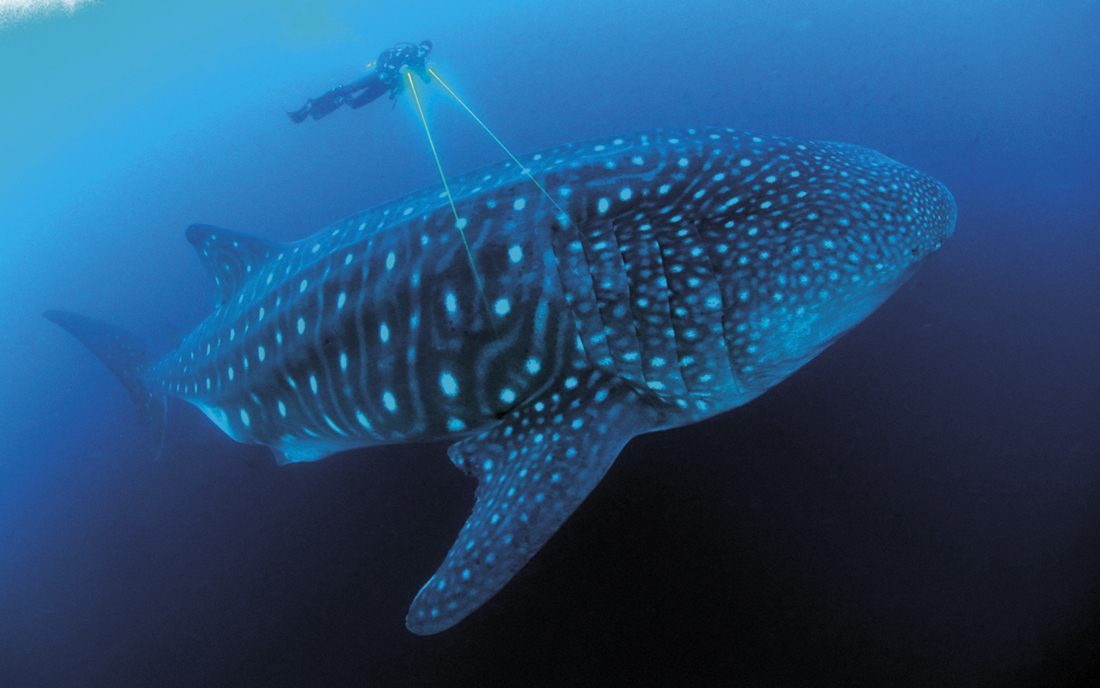

Steve Clarke reveals the ordeals of the human heroes who captured the awe-inspiring images of Blue Planet II

Professional skill, time, money and the latest camera technologies are all vital to making landmark natural-history shows. Less well known, when it comes to seeking unique footage of life deep in the world’s oceans, is how programme-makers put their health on the line.

The lengths that these men and women go to in the cause of producing iconic TV was explained in detail during an RTS event, “Diving beneath the waves – the making of Blue Planet II”.

One of the most successful series of recent times (see figures below), the seven-parter presented by Sir David Attenborough was the result of 125 separate filming expeditions undertaken over four years.

Around 1,000 people across the globe were involved as the BBC’s Natural History Unit corralled oceanographers, scientists, conservationists and local fixers and divers to make jaw-dropping TV.

The collateral damage included several bleeding ears. Sarah Conner, an assistant producer and “hardcore diver” on the team, suffered from a middle-ear infection and acute nausea.

“I don’t know if what I did was brave,” she told the RTS audience. “We all came to Blue Planet II with a lot of experience. We take to the seas after a lot of research, so we know what to expect.

“We were given 50 pages of risk assessment, which tell us about everything that could happen and how to mitigate any risk. We are totally prepared. When you are down there you are in work mode. You have a job to do. It’s an amazing job, but it is still us going there to deliver the product based on our experience and research.”

Part of the job involved kneeling on the ocean floor for several eight-hour shifts, in sub-zero temperatures and utter darkness, using rebreathers, to direct cameraman Hugh Miller.

“We all came back with our limbs intact. There were a few bleeding ears”

Her extraordinary patience, not to mention stamina, was deployed to get pictures of a Bobbit worm. These fierce creatures eat fish and can grow up to a metre long.

In common with a lot of other animals, they often play hard to get. Their natural reticence was exacerbated in waters chilled by an El Niño weather system, rendering them less active than usual. It wasn’t until various lighting configurations had been tried that the deep-sea monster finally emerged from the seabed off the coast of Indonesia and filming could commence.

“I was kneeling there in complete darkness. It was a bit chilly,” Conner recalled. “Your imagination [plays tricks on you] and I did end up with an ear and sinus infection, and nausea. When I got back to the boat I threw up.”

It was Conner’s efforts that made it possible for viewers to see the Bobbit worm stalk and capture its prey in episode 3. The scene is widely regarded as one of Blue Planet II’s most terrifying sequences.

and James Honeyborne (Credit: Paul Hampartsoumian)

The audience at the RTS event was shown a number of clips revealing how the programme was filmed. In one, crew members were seen filming from inside a small submarine as it was attacked by sharks.

The predators were distracted by the presence of the sub from feasting on the decomposing body of a whale, which was lying 700m below the surface, a gruesome sight never filmed at that depth. After a few minutes, they lost interest and returned to tearing lumps of meat from the whale carcass.

“We work with only the best underwater teams, people who’ve been at it a long time and really know what they’re doing,” said series producer Mark Brownlow. “It is their professionalism that enables us to do what looks dangerous and risky. Health and safety is fundamental to what we do. There is so much risk analysis and so much vetting.

“We all came back with our limbs intact. There were a few bleeding ears.”

Executive producer James Honeyborne added: “Everyone involved has a passion for the ocean, that’s what unites the team. For all of us, the health of the oceans is really important. There is a driving passion and a dedication.

“The ocean is an alien, dark world, cold and full of slimy fish, which is sometimes terrifying. How would people sit at home on a Sunday evening and feel a connection to this world?

“People put in the hours and put up with the hardships to do it. Ice diving is uncomfortable but you do it because, if you want to show that world.… It’s the professionalism of the crews that enables you to work in such a hostile environment as the ocean.”

Honeyborne, who commissioned Blue Planet II, told the session’s chair, Torin Douglas, that, in conceptualising Blue Planet II, the aim had been to bring new stories to screen that viewers could connect with emotionally.

To find these stories, connections had to be made with the scientific community. He explained: “That relationship with oceanographic institutes, with individual scientists and also with dive communities around the world who are out there seeing stuff …That was going to be the source of our new stories.”

He added: “The ocean is an alien, dark world, cold and full of slimy fish, which is sometimes terrifying. How would people sit at home on a Sunday evening and feel a connection to this world?

“We realised that would be our biggest challenge. Ultimately, we wanted people to care about this world.”

Putting together the epic series required extensive planning. The first task was to divide the programme into separate episodes and ensure that each one felt distinctive.“Different habitats allow you to do that,” said Honeyborne. “One on the green seas, one on the big blue, one on coral reefs.… The series starts to carve itself up.”

At the beginning of the process, much of the content was sketchy, to say the least. “A lot of those stories come to you in the second or third year of production, when you’ve won people’s trust and confidence,” said Honeyborne.

Serendipity played a big part. The story of giant trevally fish, which leap out of the ocean to grab terns, arose when a contact told the production team that he’d seen it happen.

“We looked into it. There were no records, but we thought, ‘Let’s give it a shot,’” said the executive producer. “We had a very finite budget and tight deadlines but, ultimately, you are gambling on nature.”

Brownlow, who managed a core team of 25 people, explained how a total of five producers were assigned to individual episodes. Meanwhile, researchers scoured the world, looking for material. “Finding a story can take up to a year,” he noted. Narrative arcs would then be pitched to Honeyborne and story boards drawn up.

Inevitably, technology was critical in getting the shots necessary to engage audiences. Helicopter-mounted cameras, specialist pole-mounted tracking cameras and drones were all used.

The audience saw a clip showing how bespoke suction-cup cameras were attached to the backs of a family of sperm whales.

For the first time, these gave film-makers the ability to record the whales’ complete dive cycle. “We invested a huge amount of time, effort and money building groundbreaking camera equipment,” said Brownlow.

“The secret of natural-history film-making is to have minimal commentary"

WhatsApp enabled the rushes to be sent back via the internet for feedback. “It’s a [case of] constant refinement while you’re on location,” said the series producer. “Do we stay longer or do we pull the plug?… What can we do to improve it? Do we go back next year?”

A year was spent assembling the material into something that looked like TV. A single episode involved 15 weeks of editing. “We’re always trying to raise the bar and ensure the stories are compelling,” said Brownlow.

Writing the script and adding the soundtrack were, of course, critical. This meant “working with David [Attenborough] to make sure the words seamlessly matched the images. And working with our composer, Hans Zimmer, and his team in LA, to ensure that the music was evocative and helped tell the story.

“The secret of natural-history film-making is to have minimal commentary. Let the visuals and the music tell the story and set the emotional tone. And just a little bit of guidance and poetry from Sir David.”

‘Diving beneath the waves: The making of Blue Planet II’ was an RTS ‘Anatomy of a hit’ event, held on 24 April at Kings Place, London. It was chaired by Torin Douglas and produced by Sue Robertson.

Sarah Conner: Life underwater

Sarah Conner: ‘My job is to direct the underwater sequences. I’ve done a lot of technical rebreather diving.… Different diving skills are required for each type of shoot.’

Torin Douglas: ‘What does directing involve? You don’t say to a fish, “Do that again, please.”’

Sarah Conner: ‘A lot of it is to do with team management and the safety of the diving. Often, I would be in the water with the cameraman. We could be on communication devices, so we could talk about the shots we wanted to get. ‘Sometimes, you can plan shots, such as moving through the kelp. If it’s whales moving past, you have to decide if you are going in with a lens to get close-ups or a lens to get wide shots. This is based on what footage you’ve already got. You are directing the cameraman rather than the fish.’

Torin Douglas: ‘What are your qualifications for the job?’

Sarah Conner: ‘I’ve directed a lot of natural history underwater segments for the BBC and for independent companies. ‘James approached me for the development stage [of Blue Planet II], but I was already working on something else. I did end up applying to work on the series. Mark and James gave me the job.… For me, it was literally a dream job. ‘I was a contributor on Blue Peter and I realised TV was how I could share my passion and experiences, climbing and diving and other things that I’ve done.’

A spur to action on plastic pollution

James Honeyborne: ‘We always set out to provide a contemporary portrait of the world’s oceans. Had we provided a timeless classic of these amazing animals, all happily getting on with their lives, it wouldn’t have been true to the oceans as we know it.’

Mark Brownlow: ‘I was very pleased that the audience figures didn’t drop off during the course of the series. ‘People were equally compelled by the closing environmental episode as they were by prior episodes.’

James Honeyborne: ‘I think my understanding of plastic pollution in the marine environment has changed completely in the past four years. ‘Not that we hadn’t seen it before on our beaches… Weirdly, you often find the biggest deposits of plastic in the most remote places… ‘I think we are only still learning about the scale of plastic pollution in the oceans. The insidious nature of the spread of plastic… we had that incident of the baby sperm whale that had a plastic bucket in its mouth.’

Torin Douglas: ‘But the programme’s impact has forced politicians to take this issue seriously. Did this surprise you?’

Mark Brownlow: ‘You never know how the audience will react. There are always environmental groups doing great work on these issues, so what we were saying wasn’t new. ‘We were just providing a platform that got the broader message out.’

James Honeyborne: ‘TV has the ability to turn a spotlight on a subject.… As documentary-makers, it is the most rewarding thing to feel that a subject we’ve played a part in highlighting has become such a big conversation. ‘Everywhere we look, people are talking about it.’

Blue Planet II by numbers

The series involved 125 expeditions, 6,000 hours of filming underwater and 1,000 hours filming in submersibles. One trip, taking a submersible to unprecedented depths in Antarctica, took a year and a half to organise.

Out of the 125 expeditions, the team only came back empty-handed from three. The show was the UK’s most watched TV programme in 2017. Episode 1 was seen by 14.1 million people in the week it was broadcast. This was the third most popular programme of the past five years, beaten only by 2014’s football World Cup final and the 2016 Great British Bake Off finale.

The series was pre-sold to more than 30 countries.