Steve Clarke takes soundings on how voice-activated devices will impact on broadcasters

Alexa, Amazon’s ubiquitous digital assistant, is always ready and willing to help. But how should British broadcasters ensure that the tech giants don’t sweet-talk them into relationships involving voice activation that they later come to regret?

This was one of the main themes to emerge from an entertaining and lively session expertly presented by Kate Russell, a reporter on BBC News’s Click.

The audience heard how smart speakers such as Amazon Echo were present in 8% to 10% of UK homes. So would they one day replace the TV remote control, a device that’s been keeping coach potatoes sofa-bound for more than 30 years, asked Russell.

“In our house it already has,” revealed Richard Halton, CEO of YouView. “There are capabilities it gives us that are superior to a normal remote control.” For instance, Amazon Echo and Google Home have the ability to find programmes faster than the traditional remote. Also, these data-savvy companies are more effective at delivering personalisation via voice than are traditional platforms.

“On a lot of levels, voice has got huge amounts to offer the TV experience,” Halton added.

At present, voice-activated smart speakers are more likely to be used for requesting a weather update or listening to Radio 2’s breakfast show than as a proxy remote, according to the research guru Ben Page, Ipsos Mori’s CEO.

“The data shows that there is unmet interest among people who use them to control their TV. Thirty per cent of people want to control their TV by voice,” he added.

He claimed that most people’s smart speakers are idle for most of the time: “These devices have thousands of skills, but only about 3% of people who have them keep using them.”

Even so, Grace Boswood, COO of BBC Design and Engineering, said that Alexa and her kind represented both an opportunity and a threat for the BBC. “Obviously, a real priority is to get content to our audiences as easily as possible,” she said. “We are investing heavily not just in experiences that we deliver through voice formats, but also in the capability that allows us to control what we call the intent.

“So, when you say, ‘Play something, Alexa’ or ‘Tell me the news, Alexa’, that intent is owned by Amazon. It chooses the content that will be served back.…That is a massive risk for us because, while, at the moment we may be the content provider of choice, there’s nothing to say we will be in the future.

“We at the BBC want to control not just the content that people consume, but also the intent by which we serve that content.”

To remind the RTS of the resources that Amazon and Google have at their fingertips, Halton revealed that at the CES show in Las Vegas this year, Google spent $40m in one week on display advertising for Google Home.

“This is a fight between the tech giants that is like the war for the front page of the internet during the late 1990s. Then, it was about who was going to be the browser that you opened when you switched on your screen.

“Now, it is about who owns the gateway to your home…. This is a much bigger game than getting last night’s episode of EastEnders.”

So, how exactly could broadcasters and content creators protect themselves from being squeezed out by companies that had a financial interest in the consumption of their content, and who also owned the platform through which that content was delivered, asked Russell.

This would not be easy, admitted Boswood. She said that the BBC needed to fight on many fronts, including regulation, which had yet

to take on board the implications of voice-enabled devices.

“I think we need to be alive to Amazon and Google’s business interests. Perhaps, in the days of the early internet, we weren’t so conscious of the way this was going,” suggested the BBC executive.

“We need to ensure that doesn’t happen again and that we own that distribution environment. Things such as YouView and Freeview are important in this context, because they are much friendlier to public service broadcasters.”

Halton suggested that one way forward was via partnerships. “Amazon doesn’t see these devices as ways of discovering TV content, but of learning about metadata and discovery,” he said. “Equally, it is happy to export our principles, for example, around prominence.

At the weekend, at IBC, we said to Google: ‘What’s your ambition around promoting your content or your version of the owned content versus the broadcasters’?’

“Their representatives said: ‘None. If we plug Google Assistant into YouView, because the search results will appear on screen as part of the YouView user interface, then those results will always be determined by YouView.’”

As Sky and Virgin had good relationships with UK broadcasters, Google and Amazon were perfectly happy to play by our rules because they trusted Britain’s TV platforms to manage the interaction with the consumer, Halton reasoned. “But we need to get in there now and have those conversations,” he warned.

Turning to bespoke content that works for voice-activated devices, the panellists were joined on stage by Nicky Birch, an executive producer at BBC R&D. She told attendees that the corporation was making its third “voice-driven narrative piece”, having debuted with The Inspection Chamber, a sci-fi comedy produced for Amazon Echo. The latest piece of content is The Unfortunates, a collaboration with Radio 3, starring Martin Freeman.

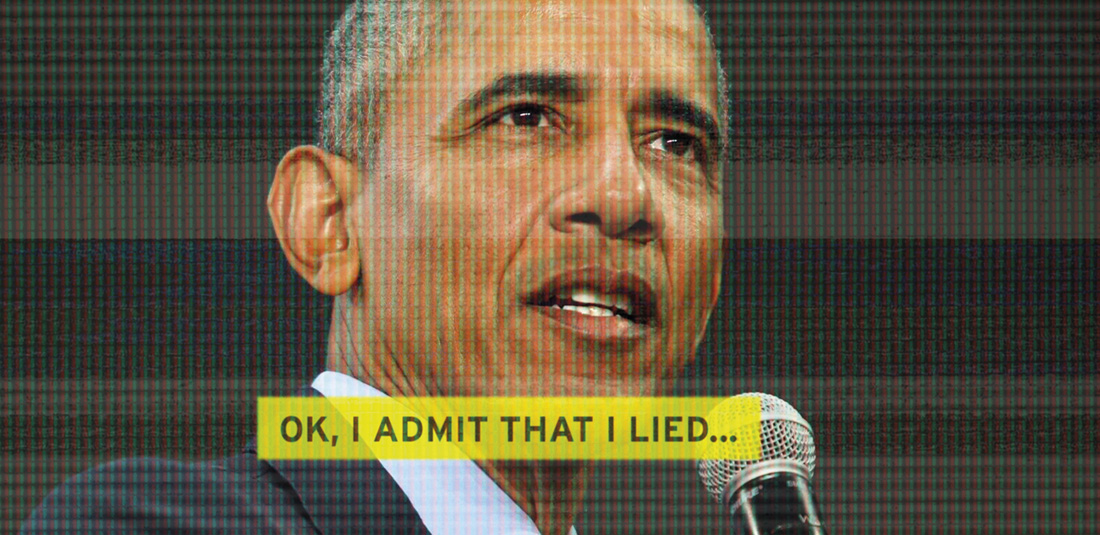

Can you believe what you hear?

well-known figures including Barack Obama

Conference attendees were shown several clips in which fake voice audio had been added to video of well-known people, including BBC News’s Sophie Raworth and Barack Obama.

Jose Sotelo, co-founder of Lyrebird, revealed that his company had developed algorithms with the ability to copy anyone’s voice using only a few minutes of audio as the raw material.

‘Record, say, 30 sentences and, based on this, we are able to create a digital copy of your voice,’ he explained.

Inevitably, doing this raises tricky ethical issues that seem certain to add another dimension to the furore surrounding fake news.

‘What we worry about is that the technology needed to build these fake videos is already available,’ said Sotelo. He predicted that it would be possible to produce fake videos containing authentic-sounding fake voices within the next year or two. ‘How would you feel if you saw a video that ostensibly featured your best friend saying horrible things about you?’

This suggested that social media abuse could become nastier still. ‘This is the scary side of this technology,’ warned Sotelo.

But there were also some potentially positive, life-enhancing applications that this technology opened up, he suggested: ‘Think about Stephen Hawking… if he had been able to have access to his own voice. Voice is such an important part of our identities. It’s easy to forget about how much they matter to people until they lose their ability to speak properly.’

He added: ‘Imagine if broadcasters could make their material available to everyone in their own language. We believe that this technology can have life-changing applications.’

Nicky Birch, executive producer at BBC R&D, agreed that there were inherent risks in technologies capable of impersonating people’s voices. She suggested one reason the British were so good at identifying fake news was because of the UK’s strong public service broadcasting culture.

YouView CEO Richard Halton said that the possibility of voice-activated content falling in the wrong hands ‘sharpens the mind on the control points that we all need to establish with these companies. The smart move is to work with them as the technology evolves, because I think that these things are very crude compared with what we’re going to see in two or three years’ time.’

He asked: ‘Do we talk enough about data and ensuring that the BBC or Channel 4 knows as much about who’s going to watch the show tonight as Amazon does?

‘There are some first-order questions around those control points that broadcasters and platforms should have. We need to get aligned around what those are. We need to ask for them and make that a joined-up partnership with Amazon and Google that allows this technology to flourish.’

Birch described the new project as more “multi-modal”, as it uses screens in addition to voice.

Russell asked if different ways of thinking were required to develop these pieces. “There are a lot of limitations but, from a content maker’s perspective, those limitations can be quite exciting,” replied Birch. “You can’t do everything you want. You want to have a truly interactive piece of content but the user is limited in what they can say.”

What did she want to see in the future? The pathway should be content-led, she said. These devices had originally been built for sales and commands but were now being used for listening to radio and music.

“As content-makers, we should be pushing what the content can do.… I’d like us to explore interactive content that is much broader than Amazon and Google allow.”

Birch added: “Imagine being able to have conversations with celebrities or [saying] ‘I want to understand a bit more about Brexit.’ There are loads of interactive opportunities around what voice can do.”

In August, the BBC launched its first children’s “voice experience”, three games aimed at CBeebies audiences and available on Amazon Echo. “We are testing the waters,” noted Boswood. “Usage is low, which is to be expected during the early stages of these technologies. I am sure there will be some killer format out there that does disrupt how we produce audio content.”

Ben Page reminded delegates of an intriguing statistic – 60% of people who have a smartphone say they have used voice-activated commands. “There’s definitely opportunity there,” he said. “Consider the BBC’s huge archive – how do you find things easily and quickly? The iPlayer is great, but it’s still a bit clunky. If this thing is going to let me very rapidly find an art history programme from way back, the potential is huge.”

Using voice to control car radios sounds like a no-brainer. As Page pointed out, changing stations via voice when driving involves people looking away from the road three times compared with 12 or 13 times using touch.

Inevitably, putting Alexa in car radios throws up interesting questions about data. “Who owns the data?” asked Boswood. “You could end up with a situation where the platform owners know more about our audiences than we do.”

Halton interjected: “They already do.… Companies such as Google are innovating at extraordinary speed, so hanging on to their coat-tails is powerful. It has to start with data.

“From our point of view, we don’t just want to know who watched the show that was voice-activated, we want to know what the context was.

"Did they ask for it straight out, or was it the next thing on a menu? At YouView, without voice control, we’re [registering] half a billion data points a day regarding how people find content, never mind what they are watching.

“Those journeys and discovery paths to content are becoming as important as viewing behaviour itself. There’s a richness of data there.

“These devices know who is in the room. By the way, they are going to know if you are sad or angry. When you say, ‘Alexa, find me something I might like to watch’, they’re going to take account of your mood.… There’s all sorts of interesting opportunities, but the conversation has to start with data and openness about it.”

“[On data,] the truth is that the Amazons and Facebooks are so ahead of us it’s quite extraordinary, but we are trying to catch up,” said Boswood. “We do have some advantages in our armoury.

“We have the content, and we have the content data, which allows us to be much more considered with the metadata tags we put in, and which show how people find things. How, when you’re sad, can the BBC give you the piece of content that’s going to cheer you up, how can we add value there?”

If this sounded spookily Orwellian, the BBC executive made it clear why Auntie needs licence-fee payers to sign in to BBC services online. Mandatory signing in was a possibility. Only then, could the BBC consistently provide better recommendations and “make your experience better”.

She admitted: “Frankly, if we don’t have that data, we’re not going to be able to compete on this content. If you like the BBC and you want us to survive, sign in.”

Session Four, ‘Rise of the machines – voice, AI and beyond – How will broadcasting embrace the challenge?’, was chaired by BBC journalist Kate Russell. The panellists were: Grace Boswood, COO, BBC Design & Engineering; Richard Halton, CEO, YouView; and Ben Page, CEO, Ipsos Mori; and there were contributions from Nicky Birch, executive producer, BBC R&D, and Jose Sotelo, co-founder, Lyrebird. The producers were Andrew Scadding, Nick Kwek and BBC Click.