How does TV news cope in an age of disinformation?

The infiltration of fake news in today’s society isn’t just a scourge for those in the newsrooms – it affects the authority of whole media brands on one side and the public’s well-being on the other. Since the term “fake news” was made Collins Dictionary’s word of the year in 2017, it has only become a bigger issue.

To prove how convincing fake news can be, attendees at this session were put to the test. Chair Naga Munchetty showed a series of viral images, with the audience deciding if they were real or fake using the poll function on the RTS Cambridge app.

While you’d have to get up earlier than even the breakfast presenter to fool the majority of the room, the point was made: it’s easy to be duped, whether it’s the image itself or the context that’s been modified. It’s why, in this divided age, when misleading information is used to sway public opinion, stamping out fake news is high on the agenda.

“It’s a very serious problem but this is journalism that we must do,” said Deborah Turness, CEO of ITN. “We cannot back away and not go there, because disinformation is the greatest threat to modern democracy and it is our job. The comparison to a war zone is very real.”

The increase in fake news has come hand in hand with the ability of ordinary phone users to manipulate images and videos – and publish the results on public platforms. Yet our brains are hardwired to believe what we see.

Questioning the reality in front of our eyes “isn’t something that we’re particularly good at because it didn’t use to be necessary”, explained Hany Farid, a professor at the School of Information, University of California, via a video link. “But now we’re being asked to reason about the world in a very different way than what our visual system evolved to do.”

"‘Some people turn to… the echo chamber that affirms them because they don’t feel understood by mainstream media’

Now that fake news has entered the realm of mainstream platforms, the onus is on the individual to choose which pieces they believe.

When that happens, it is more likely they will believe information that fits their belief system, which helps to further divide already divided societies.

“In the US, we see greater social division, and that social divide plays into everything in society,” said Turness. “We saw images of what happened in the Capitol, which is perhaps the greatest example of where that misinformation leads, and the lack of social cohesion, which is, in part, created by the media.”

The media played a role by being seen to reflect society mainly on the east and west coast of the US, “so there isn’t a sense of understanding or listening to a large portion of the population,” said Turness. “They therefore turn to fake news, to the echo chamber that affirms them, because they don’t feel understood by the mainstream media.”

To counter the growing issue of fake news, ITN created the first fake-news-busting site in Channel 4 News’s FactCheck, in 2005. Sky News data specialist Matthew Price explained that the channel used data journalists to provide visual context to stories, and forensic journalists to investigate real versus fake news.

Fellow panellist Marianna Spring investigates the human cost of misinformation, straddling the BBC’s fact-checking brands that include BBC Monitoring, BBC News Reality Check and BBC Trending.

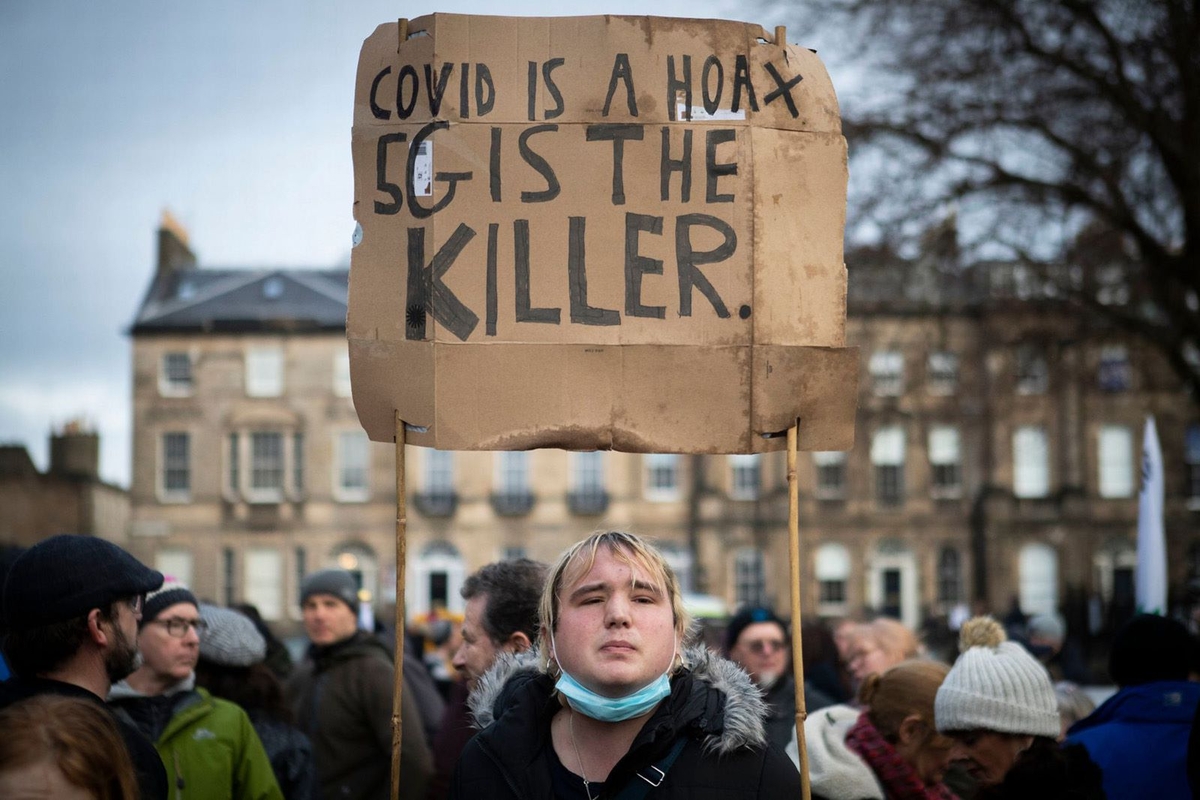

Spring offered the story of Patricia Chandler as a case study of thorough fact checking. Last year, a picture of Chandler with giant sores on her feet went viral when anti-vaxxers took information from a GoFundMe page that a relative of Chandler’s had set up and claimed the sores were caused by her involvement in a vaccine trial.

Spring was tasked with investigating the story. Even the first step of seeking out Chandler was tricky, as she had changed her name online to hide from anti-vaxxers “and everyone in Texas, where she’s from, appears to be called Patricia”.

When Spring eventually found Chandler, she told her side of the story and gave Spring permission to speak to her doctor and those running the vaccine trials – who confirmed she had been given the placebo and not the vaccine. It couldn’t, therefore, have been responsible for the sores, which were most likely a reaction to another drug she was taking.

“Verifying these kinds of stories is so complicated because they involve medical records or personal details,” said Spring. “Often, people are unwittingly exploited by anti-vaccine activists, who will misappropriate their stories. We’ve seen that happen a lot, which is worlds apart from the legitimate medical, professional or political debates we might have about vaccines or side effects.”

Yet, when debunking stories, there was inevitably a concern about amplification. “Which pieces of fake news do you choose to debunk,” asked Turness, “because you might actually be giving them more oxygen. FactCheck is careful about that – it only tackles the stories that have already been widely shared, and really need debunking.

“There’s a danger in some of the work that Facebook is doing; sometimes, when it is debunking something that hasn’t actually had many shares or likes, you’re perpetuating the story.”

Another weapon in the fight against fake news was maintaining the authority of traditional media – which meant even the smallest story had to be accurate. “It’s still about journalism, and it’s still about checking,” said Price. “If you continue to keep that at the heart of everything that you do, while it doesn’t tackle the misinformation that is out there, it does make sure that what we as journalists are putting out is correct.

“If we’re putting out stuff that isn’t true or isn’t all it’s reported to be, then we undermine our own journalism, and we add fuel to the fire for people who say you can’t trust us.”

In terms of demonstrating authority, there was a move towards increasing transparency around news reporting and explicitly highlighting the steps that news teams take to ensure their reports are robust. “I think it’s absolutely crucial that, as journalists, as television-makers, as content-makers, we start to show our workings,” said Price. “Because, if we can show the way in which we get to the conclusions we arrive at, then we can start to rebuild trust [in broadcast news].”

The final lesson was the importance of repeating facts, especially those with a public interest element, to make sure they were widely understood. “Those of us here are news junkies. I imagine most of us in this room believe that vaccines are safe because we’ve taken in that news. But many people don’t take in the news in the way we do, so we shouldn’t be afraid to repeat what we know to be true and why we know it to be true.”

While the first releases of fake news caught many in the media unaware, there is an ever-growing bank of experience to deal with further outbreaks. As newsrooms have known for decades, information is power.

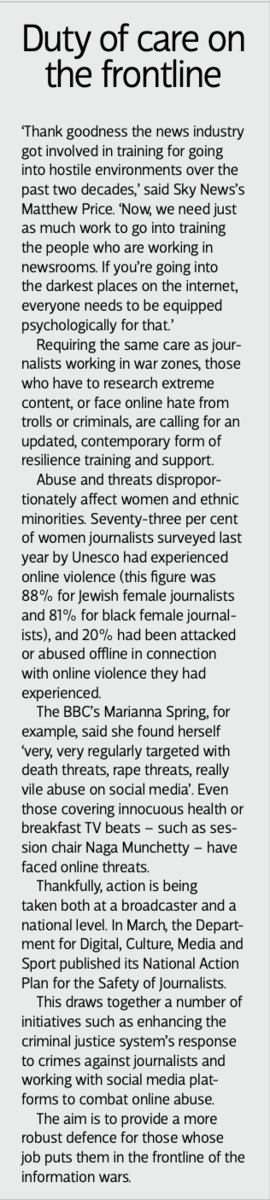

Session Thirteen, ‘Fake news: The broadcasters’ dilemma’, featured: Sander van der Linden, professor of social psychology in society and director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, University of Cambridge; Marianna Spring, specialist disinformation and social media reporter, BBC; Matthew Price, editor, Data and Forensics Unit, Sky News; and Deborah Turness, CEO, ITN. The session was chaired by the journalist and presenter Naga Munchetty, and produced by Stuart Denman. Report by Shilpa Ganatra.