The RTS hears how an angry nation united in response to ITV’s seminal Mr Bates vs the Post Office

Mr Bates vs the Post Office belongs to that handful of British TV dramas – think Cathy Come Home or Queer as Folk – that changed the world we live in, but the shocking truth is that it almost didn’t get made.

This was one of several remarkable insights shared with the RTS into the four-part ITV series that finally drew the public’s attention to what may be our broken nation’s gravest miscarriage of justice ever.

At a packed RTS event, “Mr Bates vs the Post Office: How drama can change society”, the audience heard how one of the founders of factual specialist Little Gem read an article, four years ago, in the Sunday Times colour supplement. The piece highlighted how hundreds of sub-postmasters’ lives were ruined by a mendacious conspiracy of silence over faulty accounting software installed by Fujitsu at branches of one of Britain’s most trusted institutions.

Within hours of Mr Bates vs the Post Office airing on New Year’s Day, social media lit up with Britain’s anger at how these people, often vital to the smooth working of their communities, had been treated by the Post Office.

“We tapped into a feeling of rage in the country that, all too often, people who are supposed to have our backs, who run our country and who run our companies… are liars and bullies and cheats,” ex-ITV Studios Creative Director Patrick Spence told the RTS.

“And I think that was what prompted the entire nation to say, ‘We’ve been feeling this for too long. Not on our watch any more… we’re going to protect these people.’ And they were all already angry.”

ITV was expecting around 2 million live viewers for the programme. Instead, Mr Bates won an initial audience of 3.7 million viewers against stiff opposition from BBC One’s The Tourist. It was the biggest show of New Year’s Day.

The reaction online was even stronger. “One of the other executive producers, Joe [Williams], texted to say, ‘We’ve broken the internet’,” remembered Spence. Remarkably, a high proportion of viewers watched all four episodes as soon as they appeared on ITVX.

ITV’s Head of Drama, Polly Hill, said: “They chose us, stuck with us and then they got angry. It was the anger that changed everything.”

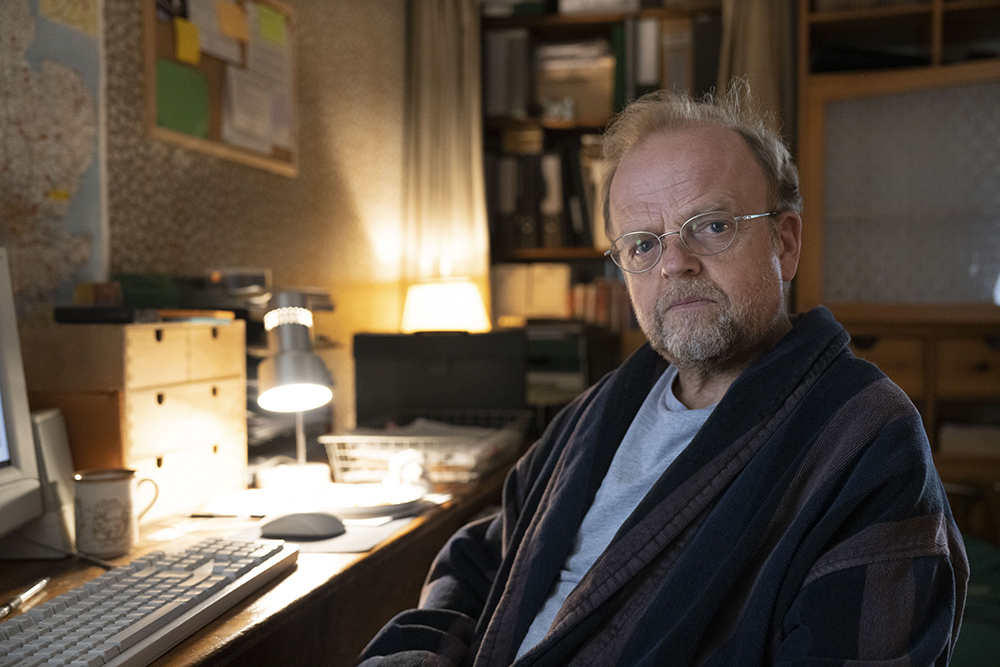

Within 10 weeks, almost 15 million people had watched Mr Bates vs the Post Office. Toby Jones, cast perfectly as the eponymous Bates, is an unlikely and unassuming hero. His dogged determination to ensure the sub-postmasters obtain justice after being falsely accused of stealing from their employer – and in some cases, imprisoned – is the pivot of the ITV drama.

Bates’s campaign is a complex story that plays out over almost two decades in the drama. The heroes are neither glamorous nor charismatic; as writer Gwyneth Hughes said earlier this year, “It’s about hundreds of people who are not fashionable, not young, not edgy, not metropolitan. It’s got nothing going for it, in a way.”

Yet, remarkably, this deceptively low-key television drama exposed a national scandal hiding in plain sight ever since Computer Weekly broke the story back in 2008. That it took a TV drama to bring this massive miscarriage of justice to the public’s attention, despite numerous news reports by broadcast and print media over many years, proves that traditional TV drama can still change the political weather and, indeed, society.

Politicians, captains of industry, the Government and tech giant Fujitsu have all been embarrassed by the show’s revelations.

The Prime Minister was caught off guard by what Mr Bates told the public about our green and unpleasant land. Little Gem producer Natasha Bondy told the RTS: “Rishi Sunak was doorstepped at a flood and the journalists asked him, ‘What about the Post Office?’.

“And he was like, ‘Oh, that happened in the 1990s’. And that irritated me because I don’t think he [has] quite understood that it didn’t [just] happen in the 1990s.” Incredibly, the victims are still waiting to be properly compensated, so the echoes of the programme continue to be felt.

Bondy explained what it was about the Post Office scandal that caught her attention: “The sub-postmasters’ stories were heartbreaking.… They lost their businesses, relationships, their mental health, their physical health – and it was all at the hands of a seemingly very benign, cosy, sweet brand that we all love and trust. Or used to trust.

“That made it really unbelievable. And also weirdly visual, because it was happening all around the country in beautiful villages, and the Post Office was this sort of dark, malevolent force.

“This sense of unfairness is why I think the country went ballistic. The nightmare of being accused of something you haven’t done was so visceral, it immediately felt like it had to be a drama. That moment [on screen] when you have the doubling of the shortfall before your eyes is such a visceral moment that viewers really remember.”

As astonishing as the story was, Spence knew that, for Mr Bates to succeed in attracting viewers, star casting was essential. “Polly [Hill] told me that we needed to have many much-loved actors in the show, so people would go, ‘If all those people are doing it, I need to watch it.’”

Natasha Bondy, James Strong, Chris Clough and Polly Hill

(Credit: Paul Hampartsoumian)

But the budget for Mr Bates was stretched. At one point, prior to the commencement of filming, there was a very real risk that the project would implode due to lack of money.

Spence recalled: “There was a very uncomfortable point in the lead up to filming when the wheels very nearly came off and Polly made a phone call that kept it alive. Without that, we would have fallen apart – Mr Bates would not have been made. The funding of four-part non-crime shows such as It’s a Sin, This Is England and Mr Bates is in serious danger” due to their need to have international appeal (see box below).

Even so, everyone involved in making Mr Bates, including the cast, agreed to accept a cut of between 20% and 30% to their fee “because they believed in the show”, Spence told the RTS.

Hill described the first time the cast got together with the script: “It was the most moving read-through I’ve ever been to. Patrick [Spence] made a speech that made me cry. I went round thanking all the actors and they all said, ‘This is why we want to act’. Everyone was invested in telling this story. It was amazing.”

It was, of course, essential that Mr Bates was legally watertight given the Post Office’s willingness to be litigious. Hughes came up with the idea that all the dialogue spoken by Post Office CEO Paula Vennells should be based on words used by her either in emails or in minutes taken at various meetings that lawyers tried to redact.

“We didn’t want the Post Office to have a chance to correct anything,” said Spence. “It had to be a matter of fact that she had used those words.” That way, Mr Bates could not be accused of being inaccurate; nor could the Post Office use the courts to stop the programme being shown.

“As if Lia Williams [who played Vennells] needs to prove herself as an actor it is worth pointing out that the incredible, naturalistic performance that she gives is based on dialogue written by Paula Vennells herself in emails,” emphasised Spence.

After the outrage generated by the drama Vennells handed back her CBE.

Spence revealed that Alan Bates was concerned about how he would be portrayed in the series. He said: “There was a conflict between us, as a programme-making team, and Alan, over what we’re going to call his emotional journey. He passionately believed he never felt one emotion across 20 years – otherwise, he would have gone crazy.

“As programme-makers we would often say to him, ‘We don’t believe you.’… We needed to track his emotional journey without betraying his trust in us that we wouldn’t play him as a hugely emotional man.”

Hill recounted how she was present when Bates thanked Spence for having delivered such a brilliant show. “That moment was really moving,” she said.

Added Spence: “Alan was very, very wary of us. But by the end he did feel – and I think these are the exact words he used – ‘You have captured the suffering of the sub-postmasters’ community better than anyone so far.’”

Monica Dolan on playing her part

Panellist Monica Dolan described how she prepared for playing Hampshire sub-postmistress Jo Hamilton, wrongly accused by the Post Office of theft and fraud.

‘I was very lucky because she was a lot more approachable than many real people who I’ve played.… When I walked through the door at the read-through, Jo Hamilton was the first person I saw. We gave each other a hug…

‘I talked to her a lot. Sometimes, it’s more helpful to watch footage of the person or watch them meet someone else because you can be more objective…

‘Jo was very open, so I asked her if she wouldn’t mind sending me an audio recording of her life up until the point where the script starts. That was so useful because she’d done so many different jobs and had so many different interests.

‘It also meant that I could listen to her voice every day. The voice is always useful to me because that’s the soul.’

She added: ‘Rule number one is that your character is not you, otherwise the whole thing would be awash with anger. I’m quite clinical about it and try and play the situation.’

The shows at risk of extinction

Patrick Spence: ‘To a great extent, the single film for television has died out as an art form. There are very few of them being made, however much broadcasters would like to make them.

‘We can’t afford to make them because they don’t sell internationally.… If we’re not careful, the non-crime four-parter is next because they don’t make money.… Shows such as It’s a Sin, This Is England and Mr Bates are in serious danger.’

Spence, ex-Creative Director at ITV Studios, now Managing Director of AC Chapter One, said that, although ITV, the BBC and, particularly, Channel 4, were keener than ever on British stories, there was pressure from distributors – whose role in financing shows is more critical than ever – to make shows with international appeal.

Mr Bates vs the Post Office: How drama can change society’ was an RTS National Event held at the Cavendish Conference Centre in central London on 12 March.