An RTS panel reveals how new documentary makers are unearthing subjects geared to young, diverse British audiences.

Uncovering remarkable stories, surfacing subcultures and recovering forgotten voices are what British documentaries excel at. It’s a crowded market at the top tier, where the likes of Louis Theroux and Stacey Dooley front mainstream documentary series.

In the more niche parts of the business, however, you have to keep your ear close to the ground to discover timely, youth-skewing subjects.

That is why broadcasters, streamers and production companies are on the lookout for industry newcomers ready with a killer idea. And they are looking particularly in the spaces created for emerging and diverse talent, with initiatives such as: Channel 4’s youth news strand Untold; Paramount’s black British wing, Black Entertainment Television (BET) UK; Sky Arts’ Unearthed Narratives series; Warner Bros. Discovery’s Black Britain Unspoken and Netflix’s Documentary Talent Fund.

But what is the best way to find an unreported topic to put before a young British audience? An RTS panel came together to tackle this in “Discovering new voices and stories in documentaries”, chaired by producer, director and inclusion leader Jasmine Dotiwala.

“We live in a world where sometimes you’re just telling a story in a few seconds,” noted panellist Debbie Ramsay, commissioning editor for Channel 4’s Untold. “It’s important that we don’t just gloss over things, and we go in-depth sometimes. That’s what a documentary allows you to do.”

Often, she added, people assume that “this age group doesn’t watch longer-form content, but they do. That’s what Untold taps into – those stories that young people identify with and are rooted in youth culture but are also saying something new or revealing for that audience.”

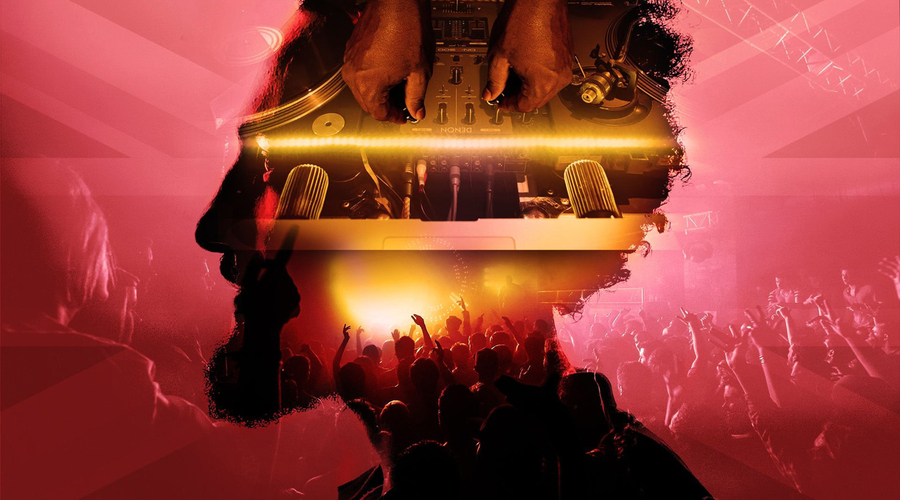

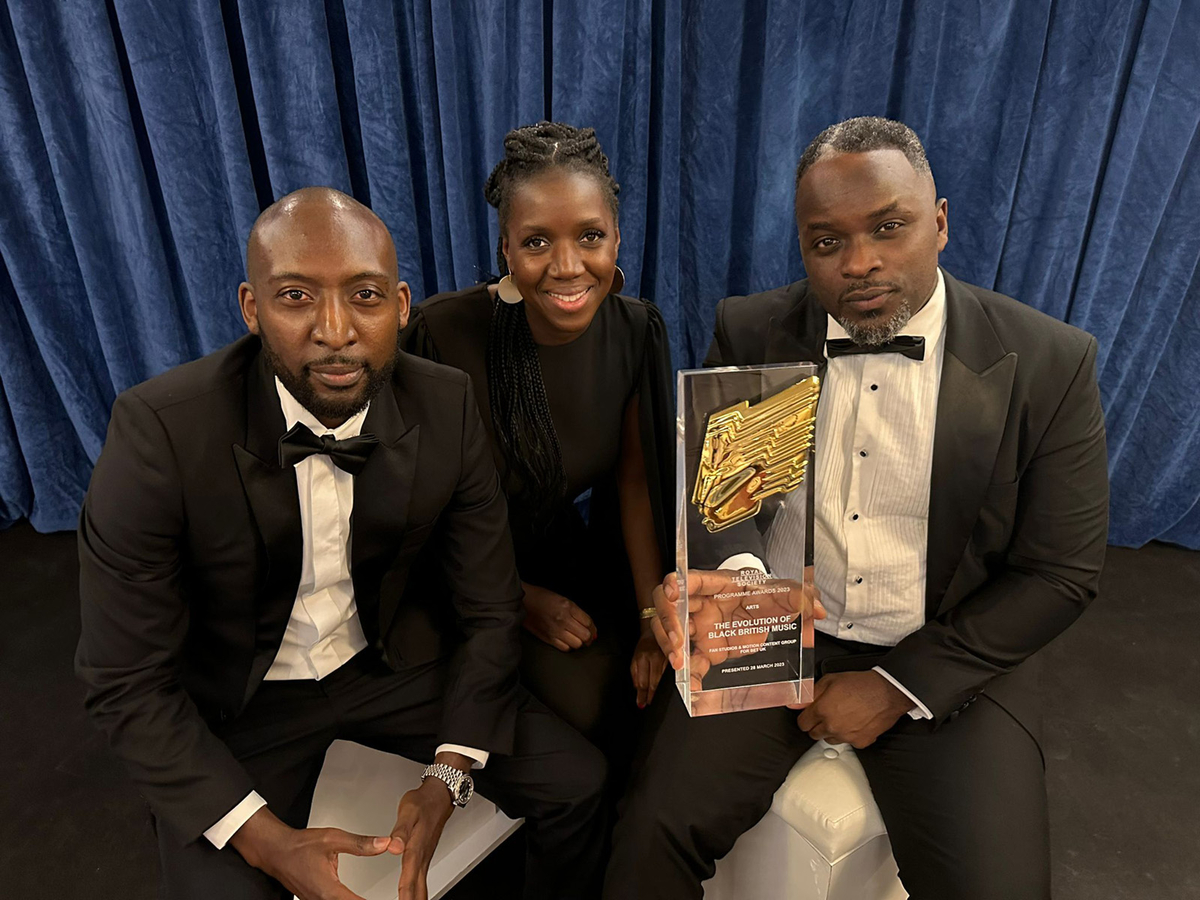

A case in point was the five-part series The Evolution of Black British Music, winner of the Arts prize at the RTS Programme Awards 2023. It documents the emergence of Jungle, Grime and Garage in the UK. The series was conceived by film-makers – and panellists – Nicky “Slimting” Walker (who has a background in acting and music) and Femi Oyeniran (who began his TV and film career in the seminal Kidulthood). Together, they formed the production company Fan Studios and came to the attention of fellow panellist Cicelia Deane soon after she started her job as Editorial and Commissioning Executive at BET UK in 2021.

Deane recalled: “I was introduced to Nicky and Femi via another commissioner at Paramount because they’d made a series called Drunk History: Black Stories. Nicky and Femi pitched loads of ideas and we got on like a house on fire.”

Her remit is to commission for black British audiences and tease out stories that haven’t been told. “And there are so many, unfortunately,” she said. “The Evolution of Black British Music should have been made a long time ago.”

How does she decide which ideas are green-lit? “My slate is broad. I don’t have a huge commissioning budget. When I meet with people, it’s quite instinctive,” she said. “The buck doesn’t stop with me. I have to then pitch it to my seniors, so it has to be something I’m passionate about.

“Because I don’t have a lot of money to commission with, on the brief I send out [to producers] I’ll always include a list of what I’m not looking for. That’s normally because I’ve just commissioned something in that area.”

Like all good producer-commissioner relationships, the process of shaping The Evolution of Black British Music was symbiotic. Walker, who’s made documentaries for both Deane and Ramsay, explained: “It was important that the commissioners respected us as filmmakers, gave us that freedom and didn’t undermine us. If they felt something wasn’t right, they articulated it in a way that we were able to digest.

“You have to respect what they’re saying because they’ve got the experience, and they’re giving you that opportunity as well. Whatever they’re telling you, they’re telling it for the good [of the documentary]. They’re in that space, and they understand what’s best for the channel.”

He added: “Both [Deane and Ramsay] were open to listening to our voices. They never made us do anything. We put our case forward, they put their case forward, and we always met in the middle. It’s like a marriage: you work with each other, you have bad days, you have good days, it goes back and forth.”

That give and take is key to the success of a documentary-maker, agreed fellow panellist Charlie Mole, a self-shooting director who has produced programmes for Untold, Panorama, Dispatches and Unreported World. “Every role is a cog in a machine,” he said. “If you’re freelance, you also need to promote yourself because you need to get work, but don’t let that impact on how you work in a team.”

Equally, “in terms of getting the story and speaking to contributors, it’s not about you, it’s about the bigger picture. Put your ego to one side, and work with people, just be friendly and kind and nice and be willing to work hard.”

That was certainly the case when he was making Untold’s The Secret World of Incels, where, unsurprisingly, the trickiest part was finding contributors. More than 100 potential participants were contacted and 25 meetings were held to get three people to appear on screen.

“The crucial thing when you’re going into these communities is that they don’t trust you. You’ve got to be completely upfront with them. We’re journalists and we’ve got a story to tell. And we are going to be challenging with them, it’s not a PR film. But, on the flip side, we will give them a fair hearing. Although we’ll ask difficult questions, we will allow them to answer and faithfully represent their story,” he said. “Once you’ve got that out of the way, I think it’s refreshing for them, because they’re like, ‘I get where I stand now’.”

There are more mundane issues involved when making documentaries for major broadcasters. Oyeniran and Walker explained that, while documentaries destined for YouTube have a lot of flexibility regarding using archive footage and sound, it’s a totally different situation when working with broadcasters.

Expect a lot of form-filling and permission-seeking if working on a music documentary. “It was insane. It took months and months,” said Walker, recalling his experience on The Evolution of Black British Music.

Oyeniran added: “We had a situation where the episode was supposed to go out, but it couldn’t because we hadn’t cleared a song. In order for it to go out we had to contact [Grime performer] Skepta’s manager, but they were doing a show in Ibiza for the whole week. These guys are in a club in Ibiza, Nicky’s harassing one person, I’m harassing the other person, and this person’s texting that person. Then randomly, we got an email the night before the show was supposed to go out, saying ‘Here it is’.”

Finally, Dotiwala asked the panellists if they had any advice for those taking their first steps in documentary-making. Walker said: “Put yourself around like-minded people. Try to get as much work experience as possible, even if you start off as a runner. Immerse yourself in that arena. Be open-minded. Shadow people. Really be passionate about what you’re doing because it’s a long journey and there are loads of people who want to do it. Everyone’s special in their own unique way, but you have to go the extra mile to be noticed.”

Report by Shilpa Ganatra. The RTS event ‘Discovering new voices and stories in documentaries’ was held on 3 July. It was produced by Jasmine Dotiwala, Elaine Okyere and Ethel Mercedes.