Andrew Billen discovers that Sky COO Andrew Griffith boosts his energy levels at work by avoiding sitting down.

When, each morning at 7.30am, Andrew Griffith arrives at his office at Sky’s impressive new central block in Osterley – the one in the background on Sky News – he does not slump in his chair. He does not have a chair.

This is not a case of fanatical hot-desking, although he is one of the few senior execs to have his own defined space in the new building. Sky’s 45-year-old chief operating and chief financial officer prefers to stand: better energy levels, shorter conversations.

For a suit (actually, he is in an expensive but open-neck blue shirt when we talk), he strikes me as a man of action. On his left, by a 4K TV, lie a replica revolver and a baseball bat. I am sure there is nothing to be alarmed about.

I ask about the atmosphere at Sky as the planned, £11.7bn takeover by Fox grinds on. There is nothing new to say, aside from “business as usual”.

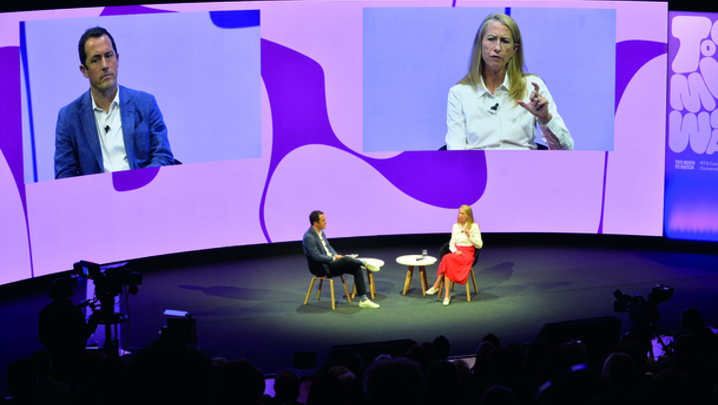

I move instead to the RTS Cambridge Convention, which Griffith and Gary Davey, Sky’s managing director of content, are jointly chairing and which will star his ultimate boss, James Murdoch, who is giving the keynote address. I ask if Cambridge’s true purpose is networking. He says, no, it provides a place to talk, and, right now, there is much to talk about. “The retinue of the industry itself is changing, but the industry is also part of things like Brexit,” he says. “There’s a lot of change in the world. It’s a once-in-two-years chance to take stock and talk about the opportunities for our industry.”

The Sky story is remarkable, and I speak as one of the first people to buy a dish in 1989 and one of the first to upgrade to a digibox and then Sky+ and, most recently, Sky Q. It began as a joke in panto and ended as one of the gorillas in broadcasting’s jungle, with 11.4 million Sky TV viewers in Britain and Ireland.

“I like to think that we’re all creative. We certainly don’t ghettoise the idea of ‘you’re a creative/you’re not a creative’"

Its investment in Britain has been remarkable and innovative, not only technologically, but in programming, particularly in sports and news, changing both for ever. Sky Atlantic is as essential to viewing life in my home as BBC Two. Increasingly, the channel provides not merely must-see American series via HBO but original British series of real quality and ambition.

Yet, it does cross my mind that, following a quarter of a century of unstoppable growth, we may be reaching, at least in the UK (it has expanded now into Italy and Germany), peak Sky. Churn (the rate at which subscribers stop subscribing) remains higher than Sky would like, although a new loyalty programme is expected to bring this down. There is a lot of talk about Netflix and Amazon. Satellite dishes are beginning to look old tech.

“No,” he says. “First of all, Sky is not just a UK business any more. Sky is one of the, if not the leading, European pay-TV businesses, and we added 700,000 new customers last year, taking us to 22.5 million.

“But, second, it’s a long, long time since Sky has been defined by the dish.”

Towards the end of this year, or the beginning of the next, the full Sky Q interface will be capable of delivery purely over the web, rather than, as at present, as a net-dish combo.

“One of the successes of Sky is that we’ve always been, I won’t say technology agnostic, but we’ve embraced every form of new technology to deliver different services,” says Griffith. “So, we were one of the first to stream our channels live, and, obviously, the iPad or the tablet took that to new audiences and expanded the market still further.”

Last year, I traded up to the new Sky Q box. He is interested in the teething problems I experienced – including the first box’s replacement – and we exchange condolences over the agony and ecstasy of early adoption. Customer satisfaction scores for Sky Q are “now off the charts”. Once customers get Q, they consume more content.

Yet, a friend of mine, fallen temporarily on hard times, has given back his digibox in favour of Sky’s fifteen-quid Now TV box, with which he can pay for what he wants to see without taking out a subscription.

Griffith says that Sky does not break out how many Now TV boxes – which, significantly, are marketed without the Sky badge – are in homes right now. But he says the number is significant and that Sky’s growth will, in future, come from such “incremental customers” as my friend and from existing customers taking more products, such as Ultra-HD, mobile or buying movies.

"If we weren’t failing, I would be worried that we weren’t taking enough risk.”

“We used the pretty simplistic analogy of the BMW brand family, within which you’ve got the Mini, you’ve got the core BMWs and you’ve got those luxury ones. So, you’re going to have different products in a more mature market. You’re going to have a more segmented approach,” he explains. “The good news is that this grows the overall market.”

Following a major rejig to the Sky Sports offer last month, a Premier League fan can now add a channel showing that sport alone to their Sky package for just £18 a month.

Should it be lowering prices on a premium product? “Well, premium is the function of the quality of the product, not the price,” Griffith responds. “We don’t take a fee and just quadruple the price and expect it to be perceived in any different way. As ever, as a business, we’d like more customers. The value of lowering price is just to make it easier for new customers to find what they want and, ultimately, give them more value.”

Last year, Sky paid an extra £629m for Premier League football rights, yet only reported a drop in profit of £97m as revenues grew and costs were curtailed. (delivering a still not-to-be-sneezed-at £1.3bn). The paradox is, I say, that competition between Sky and BT has made football more expensive for viewers.

“To watch Premier League for just £18 a month, with the high-quality production values and the way we support the game, is, I think, good value,” he replies.

The rights bidding process does not – as I had always assumed – happen in an airless hotel room, but by email, after months of analysis. Does that part of the job stress him? “There are a lot of things that I feel stressed about.”

He says that non-sports subscribers do not subsidise the sports watchers – “Why would we do that?” – and points out that the growth in Sky’s customer base is no longer driven by sports but by new, drama-heavy services, such as Sky Atlantic and Box Sets.

He mentions Riviera as a home-grown drama hit (downloaded 17 million times) and is clearly an admirer of Guerrilla, but I wonder if, overall, he thinks Sky drama is quite there yet. “Oh, you’re never there. I’ve been here for 17 years and, while it would be tempting to declare victory, it never happens.”

Of course, there will be disappointments, too, such as series 2 of Fortitude.

“We’re in the business of taking creative risks,” he says. “That is at the heart of the content business and so, you know, it’s good to fail sometimes. If we weren’t failing, I would be worried that we weren’t taking enough risk.”

He grew up in south-east London, the oldest of three brothers. His father, John, was a manager at an IT company. His late mother, Janet, stayed at home to look after the family. He went to a comprehensive in Sidcup.

“Growing up in the 1970s, I was still in an era that remembered the test card. TV was something that happened in the evening and was a deliberate activity.”

Did he have ambitions to work in TV? “I’m sure that, when I was very young, train driver and pilot featured quite prominently among careers that I might have considered. It’s certainly true to say that it was not my ambition to end up as chief operating officer of Sky.”

He went to Nottingham University to study law because it was an “interesting degree”, but he quickly realised that a solicitor’s life would be very far from the intellectual study of law. More interested “in the general idea of business”, he spent three years qualifying as a chartered accountant at Coopers & Lybrand Deloitte.

From there, he worked for three years at Rothschild investment bank, advising corporate clients in the media and telecoms sector. He joined Sky in 1999 on the same day as his flamboyant boss, Tony Ball, just as the switch to digital was happening.

It was, he says, a big cultural change from the City to the “environs of Brentford. It was not as nice as it is now. It wasn’t quite the shed where we started, but it was much closer to that than we are now.”

Did he – does he – mix with the creatives? “I like to think that we’re all creative. We certainly don’t ghettoise the idea of ‘you’re a creative/you’re not a creative’. Our creative people are business savvy and our business people are creative savvy.”

Did his city-slicker friends say, “What are you doing, Andrew?”

He smiles and says: “I’m sure many of them did. And Sky itself was much less a proven winner in those days. We had just over 3 million customers. People were still debating whether Sky would be a success, not debating to what extent it would be a success.

“But there was something about Sky’s attitude that attracted me. It was a challenger. It wasn’t an incumbent.”

The question is whether Sky is still the challenger, or has become the incumbent, and one with a typically lavish corporate HQ.

“But we’re still the disruptor,” Griffith insists. “We just find new ways to disrupt. So, you know, mobile [phones]. If you talk to any of the big mobile operators in the UK and ask, ‘Who do you fear?’ Or, ‘Who’s disrupting your industry?’ someone like Sky would come off their lips pretty quickly.”

The more I talk to Griffith, the more I can see why shareholders might wish to pay the high salary he commands.

He knows how to generate profit, whether by (annoyingly) placing commercial breaks in Game of Thrones (HBO in the US doesn’t), or by targeting commercials to each and every Sky TV screen individually through a system called AdSmart (for which he is too modest to take sole credit), or by adding new customers.

What is life like outside work? “I work pretty long hours. I do attend a lot of industry functions, but that’s because I love our industry. I love what I do. It’s not about what I get paid.”

Do his two teenage children complain they don’t see enough of him? “I think everyone would like to see more of their kids. That’s important. And mine are growing up fast.”

Back in 2001, and again four years later, Griffith stood as a Conservative for Parliament.

He told the local press he would put the needs of his constituents before a ministerial career. Both times, he lost to Labour.

One wonders what would have happened had he won. Let’s just say, Philip Hammond might have a serious rival for his job.

Griffith’s reach for the Sky

Andrew Griffith, group chief operating officer and chief financial officer at Sky

Married since 1997, to Barbara, volunteer charity worker; one son, 15, one daughter, 13

Lives Putney, south-west London

Born February 1972. Brought up in Bromley, south-east London

Parents Father, John, IT salesman; mother, Janet; two brothers

Education St Mary and St Joseph’s School, Sidcup; Nottingham University (studied law)

1992 Trainee chartered accountant, Coopers & Lybrand Deloitte

1996 Rothschild investment bank

1999 Joins Sky

2001 and 2005 stands as Tory parliamentary candidate for Corby

2008 Chief financial officer, Sky

2016 Chief operating officer, Sky

Watching House of Lies (comedy about self-loathing management consultant); 8 out of 10 Cats Does Countdown

Hobbies Travel and his pet Labrador

First satellite dish 1999 (when he joined Sky)