Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse makes a passionate case for science’s capacity to effect positive change. Matthew Bell reports

Sir Paul Nurse delighted his large audience with a passionate defence of science as a revolutionary force that can transform our lives, when he delivered this year’s Royal Television Society and Institution of Engineering and Technology Joint Public Lecture at the British Museum.

In a wide-ranging speech, the Nobel Prize-winning geneticist discussed the approach to science in the media, government and education. And – in advance of the EU referendum – gave strong backing from the scientific community for staying in Europe.

The main thrust of Nurse’s lecture, “Science as revolution”, was that, throughout history, science has been a highly revolutionary activity. This, he argued, remained the case and science would, provided “it is nurtured and the public properly engaged, continue to bring great benefits to us all”.

Nurse was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2001 – with Leland Hartwell and Tim Hunt – for work on the cell cycle. He is currently Director and Chief Executive of the Francis Crick Institute, which conducts research into the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of serious illnesses.

Nurse on… politicians and the EU

‘Both government and parliamentary scrutiny procedures must be fully aware of how science can contribute to policymaking, by ensuring that they have access to the highest-quality scientific advice – and by heeding that advice,’ argued Sir Paul Nurse.

He added: ‘Scientific evidence and argument must be listened to and treated with respect.

‘For this to be effective, scientists must adhere to the highest standards of behaviour. They need to be open and honest, free from hype, and be absolutely clear about what knowledge is more certain and what is more tentative. This can be difficult when politicians and the public demand certainties that cannot be delivered.’

BBC Worldwide CEO Tim Davie, who chaired the joint RTS/IET event, asked Nurse to score UK politicians for their support of science.

‘In Britain, we are among the best in the world. Certainly, a B+ – at least for some of them,’ he replied. ‘Often, scientists say that we need more scientists in government – I don’t think that’s true. We need to have politicians in government who understand how science works and know how to get advice from science.

‘We have some champions of science in government at the moment, and we are heavily reliant on them. George Osborne, and Gordon Brown before him, are both champions of science.

‘I have to go to them every time if I’m trying to develop something, because mostly I am listened to politely but I can’t get access.’

Nurse argued that the UK scientific community strongly backed staying in the EU, although the media’s understandable quest for balance could make Brexiters seem more numerous than they were. ‘There are only two [from science] that I’ve seen in favour of EU departure and they are [interviewed] all the time, as if there were thousands of them,’ he said.

‘If we want good science in this country, we have to stay in the EU.’

Nurse on… television and the media

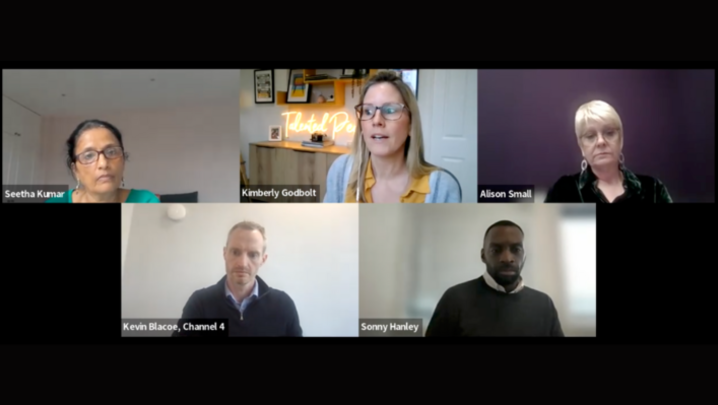

(Credit: Paul Hampartsoumian)

The mass media, including television, has to be ‘highly responsible’ in its reporting, said Sir Paul Nurse. ‘[It] needs to avoid sensationalism; to be careful about so-called balance, when certain opinions have little evidential support or are potentially highly flawed, to avoid mystification; and to properly explain what can be difficult topics.

‘There are excellent communicators of science in the mass media and they should be given every encouragement,’ he added. ‘Let us not underestimate the power of the mass media. Look at what happened with [Sir David] Attenborough and how interest in natural history and zoology [grew] 30 years ago. Look at what’s happening with Brian Cox and physics today.’

Great advances in sciences, Nurse argued, were ‘usually driven by creative and technically capable individuals’. He drew a parallel with television, which also required ‘collaborative teamwork and creative, technically competent individuals. In both spheres of activity, good practitioners are often rather anarchic – trying to organise or manage them is like herding cats.’

But he warned that science was under threat, particularly from ‘those who mix up science, based on evidence and rationality, with politics and ideology, where opinion, rhetoric and tradition hold more sway’.

In response to a question from the audience on scientific misinformation spread by the media, Nurse said: ‘Scientists like me have to be on the front foot in correcting those errors.’

Initially, this should be done ‘politely and courteously’, but, he said, firmer action was needed for repeat offenders: ‘When they serially offend, we should crush them and bury their ideas.

‘I don’t think the press does a bad job. I often think that science journalists do an excellent job, only to have it ruined by a terrible headline or a piece of spin, and that is very unfortunate.’

Nurse on… science in school

‘For science to play its proper role, we require a public at ease with science and a democracy that can cope with the complex decisions involving science,’ stressed Sir Paul Nurse. ‘This needs to start in our schools.

‘We have to provide a science education that not only trains future scientists for the next generation – that’s only a very small fraction of the total population of schools – but also trains future citizens to cope with the increasing effects that science will have on our democracy.

‘Students need to be aware that science is a way of thinking, of experimenting and making observations, of weighing up evidence.

‘They need to know that science can be tentative in its conclusions, but can also lead to advances in knowledge of the world and of ourselves.

‘Science is not simply a series of facts and figures, although some of these can be extraordinary, stimulating and inspirational: science is a process that builds reliable knowledge. Every student who leaves school should, for example, know the difference between astrology and astronomy – I doubt that more than 50% do at the current time – and between the theories that underpin homeopathy and evidence-based medicine.

‘A key requirement of a modern education system must be to equip a future citizenry to cope with the impacts that science and technology will have on their lives and on the proper functioning of a healthy democracy.’

Nurse elaborated on these thoughts during the question and answer session that followed his lecture: ‘In schools, we have to have inspirational teachers, and it is difficult to be an inspiring teacher in a difficult subject such as science.

‘[School] shouldn’t be about learning the periodic table; it should be about understanding the basics of the periodic table.

Nurse on… revolutionary science

‘When we think of revolutions, we usually consider major transformations in the spheres of politics, economics, social organisation or religion, and not of science,’ said Sir Paul Nurse.

‘But to these we should add the revolutions brought about by science, both cultural – through improved knowledge of the natural world and of ourselves – and through the major impacts that improved knowledge can have on… human civilisation.’

Nurse illustrated his lecture with examples of scientists and their groundbreaking work: Nicolaus Copernicus, who suggested the then-revolutionary idea that the Earth and other planets circled the Sun; Galileo Galilei’s discovery of Jupiter’s moons; and Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

‘The technological advances that have arisen from science have been legion: the development of energy sources; … the use of new materials… leading to the robotised factory of today; new means of transport; … and the management of information with the telegraph, the radio, the television, the computer and the worldwide web.…

‘There have been other revolutionary consequences of science for society centred on… what it means to be human. Like all other living organisms, human beings have to be understood in terms of their inherited genes, their cellular chemistry, their interactions with the environment….

‘Modern science has had another, more curious, type of impact, which I believe is also going to be revolutionary, on human knowledge. Einstein, in his theory of general relativity, proposed

a continuum of space-time to account for gravity, which undermined the common-sense view of the world expressed in terms of time and three dimensions of space….

‘Studies of atomic structure some years later led to quantum mechanics, a sort of Alice in Wonderland world, a place where Schrödinger’s cat can be alive and dead at the same time…

‘Revolutions are unsettling and often strenuously opposed. This was the case with Copernicus moving the Earth from the centre of the universe. Remember: the [Spanish] Inquisition didn’t argue with Galileo; they simply showed [him] the instruments of torture.…

Nurse on… science, ethics and morality

‘Studies based on evolutionary genetics and animal behaviour have implications for ethics and morality,’ warned Sir Paul Nurse. ‘Science has a habit of invading other domains of human activity, which at first sight appear to have no place for science.

‘This was the case for Galileo [Galilei] and [Charles] Darwin, and is still the case today. Modern scientific advances have increasing impacts on spheres of activity once thought to be the domain solely of politics, philosophy and of religion.’

Discussing the impact that science has had on ethics and morality with the evening’s chair, Tim Davie, Nurse said that science – in particular, ‘our understanding of genetics and behaviour’ – could help to explain why people act in an altruistic manner.

‘Altruism is key for personal relationships, the development of society and the maintenance of community,’ he added.

Neuroscience, Nurse argued, was another area where science could come into conflict with ethics and morality. Although it was ‘still pretty crude’, neuroscience was ‘giving us ways of understanding how our brains work, which, with it, will bring us ways in which we can actually manipulate brains. This has significant consequences. We will better understand giving evidence in court if we understand more about memory and the recall of memory.

‘We are a consequence of our genes, our environment and of how we’ve developed. Now, there may be aspects of our behaviour that are really strongly genetically determined. If that leads to, say, criminal behaviour, you have to ask yourself: can someone really be guilty of something they were born with? We have to think about these things.’

Sir Paul Nurse’s RTS/IET Joint Public Lecture, ‘Science as revolution’, was given at the British Museum in central London on 11 May. The event was chaired by BBC Worldwide CEO Tim Davie and produced by Helen Scott.