A stellar RTS panel confronted the threats posed by the tech giants to legacy media. Matthew Bell took notes

A year ago, not even the wisest media-industry sage foresaw that Rupert Murdoch would agree to sell the bulk of his empire to Disney for $66bn. The landmark deal, which was announced in December and needs to be approved by regulators in the US and Europe, was interpreted as an admission that even the mighty 21st Century Fox lacked the scale to thrive in an era dominated by tech giants.

A high-powered panel at a sold-out RTS early-evening event at the end of February confronted this and related issues in “Sale or scale”.

Recall 21st Century Fox boss James Murdoch’s comments at last September’s RTS Cambridge Convention: “Scale buys confidence to invest strategically and take risks, and supports the development of new technologies and innovation.”

Fox’s sale to Disney, Fox’s bid to own Sky outright and AT&T’s bid for Time Warner are three business moves that can be seen in the context of the advance of Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook. Days after this event, Comcast launched a rival $22bn bid for Sky.

Financial Times global media editor Matthew Garrahan, who chaired the RTS event, suggested that, for traditional media companies, this “deal frenzy” could be interpreted in one of two ways. It was either the case that “they have lost their bottle – or is it the only realistic response to the challenges posed by this new era?”

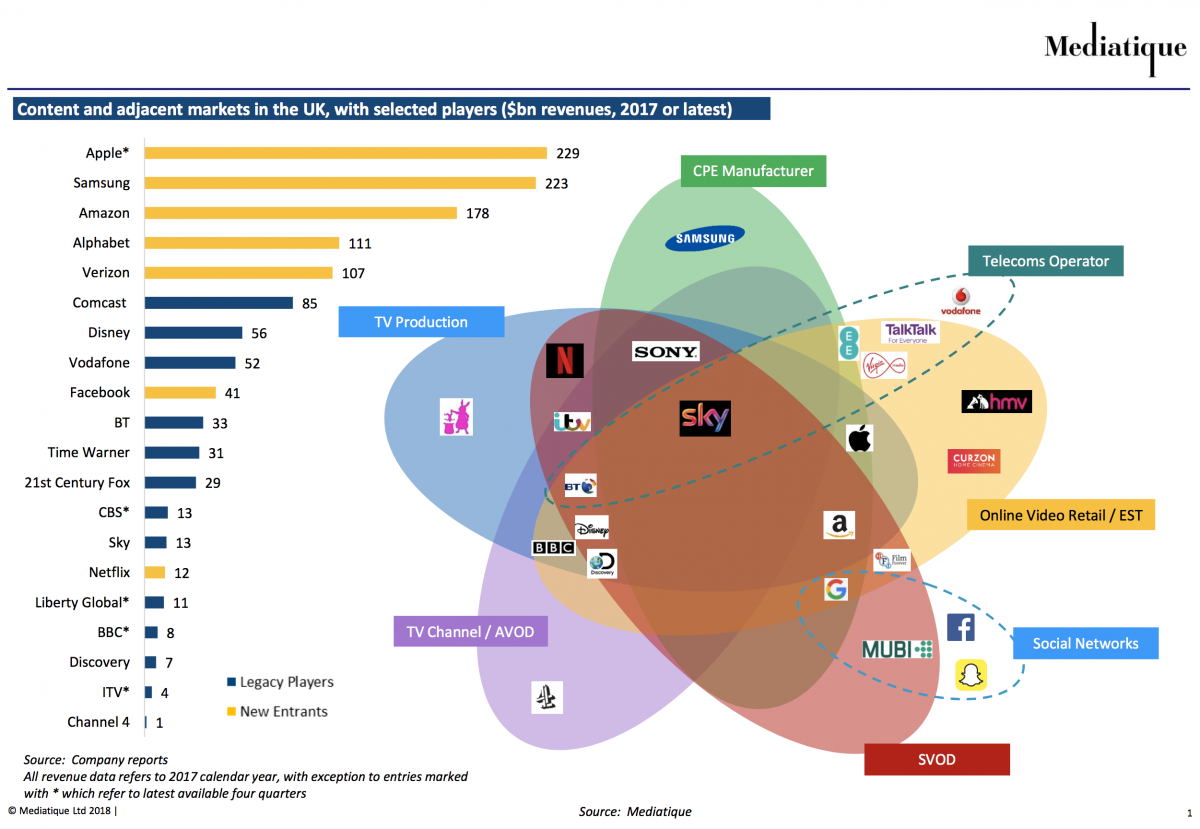

The huge tech companies dwarf TV’s traditional players, explained Mathew Horsman, Joint Managing Director of media consultancy Mediatique: “Apple’s revenues are three times those of BT, Sky, Liberty Global, the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 put together.

“Even Netflix is an absolute minnow compared with Apple, Amazon and Google,” he added (see chart below).

Mike Darcey, the former chief operating officer of Sky and CEO of News UK, agreed with James Murdoch on the necessity of scale in the modern media landscape – not least to mitigate risk.

“You need scale of investment across a [broad] portfolio of ideas to be able to cope with the risk of putting that much money on the table behind a particular idea,” he said. “Otherwise, you are betting a lot of money on red.”

But the ex-Sky man added that “vertical integration” – operating as both a media platform and a creator of content – was as important as achieving “scale”. He noted that many of the current big media deals and consolidations, such as AT&T and Time Warner, were “between a platform and a content provider”.

He added: “You could take James Murdoch’s quote from last year, take out the word ‘scale’ and write ‘vertical integration’ and the rest of it would still hold, in the sense that vertical integration can help you to manage the risk.

“If you have scale in distribution, you have more confidence to invest in content. Your platform won’t be denied content and your content won’t be denied distribution.”

There was a consensus on the panel that smaller British broadcasters are finding it increasingly hard to compete with the US behemoths. Garrahan pointed out that Channel 4 “took the risk on Black Mirror”, only to see a bigger beast, Netflix, snatch the Charlie Brooker-penned satirical series from its hands.

“The broadcasters are under pressure, but it doesn’t mean that Channel 4 is out of the running,” argued media journalist Kate Bulkley. Nor, she said, was ITV.

Referring to the title of the RTS event, she pointed out that ITV had “tried the ‘scale’ bit. It had bought a lot of production companies – and had grown pretty big. It is the biggest factual producer in the US, now. But where does it go from here?”

One route forward, she suggested, was to concentrate on local markets, by “serving their local customers much better than these big guys” and offering services that are “different to all the stuff that is coming out of America. The question is: does that make it distinct enough so that it can somehow survive?”

Mathew Horsman was blunter in his assessment: “It either [becomes] a much smaller company or someone buys it.”

Not all UK television outfits are under the cosh. “As a content creator,” said Tim Hincks, joint boss of the independent producer Expectation Entertainment, “this is a genuinely exciting [time]. We… [are] seeing more customers and demand for our content.”

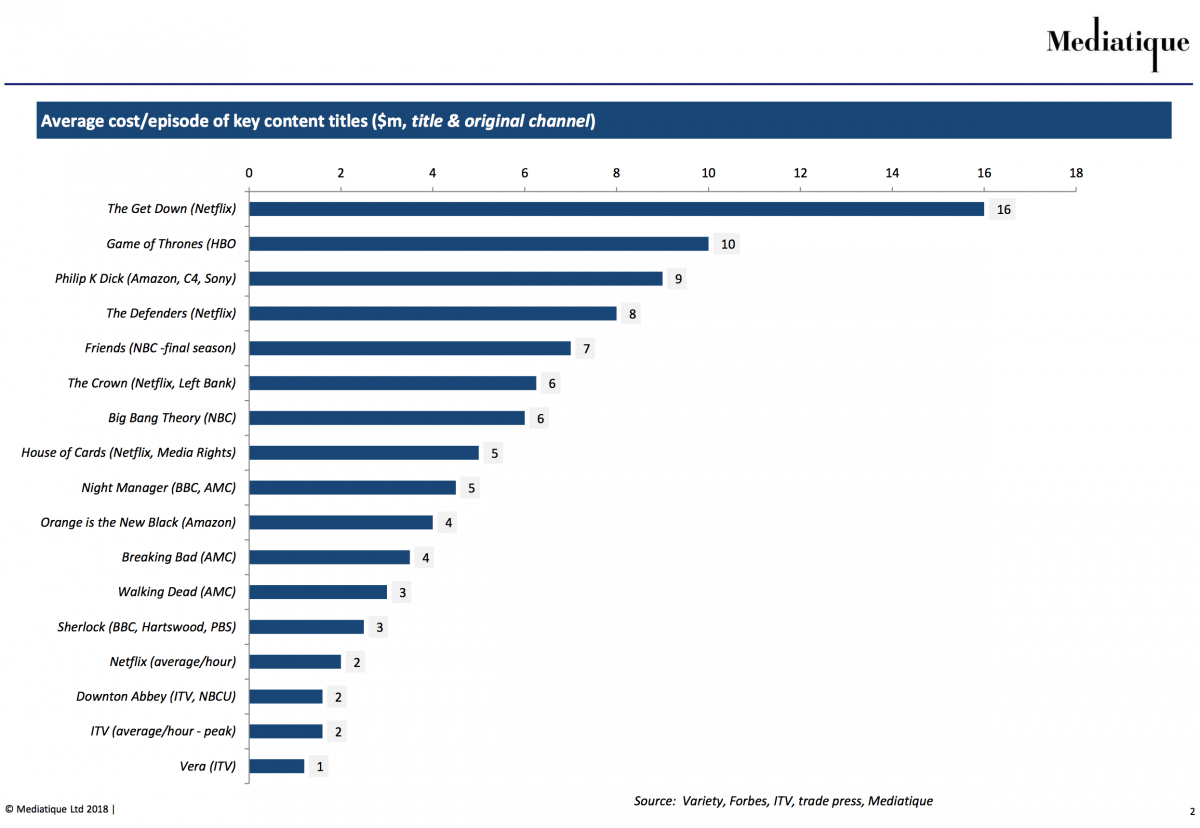

In the UK, said Mathew Horsman, the new entrants had not, as yet, stepped up to the plate, although they had had an effect on the global TV market, most notably by pushing up prices. “It wasn’t many years ago when £1m was a very big number for an hour of UK content.” Famously, Netflix drama The Crown costs five times that figure per episode.

“The inflation we’re seeing now for talent is extraordinary,” agreed Tim Hincks. “It can’t be sustainable. There are BBC dramas that are effectively 80%-funded elsewhere. There are multiple examples. That’s a very happy relationship now, but it will not last.”

The indie boss added that the “current Stella Artois approach” of making “reassuringly expensive” programming was unsustainable. On the positive side, however, escalating costs meant that now “is the best time in a while for new talent”. For broadcasters – such as the BBC and Channel 4 – with remits “that are partly about the discovery and promotion of new talent, this is a great time. There’s a lot of talent scouting at theatres, more than there has been for some time. People are going to see the new writers and performers.”

Even so, he said, UK broadcasters “ultimately cannot compete, show for show, against the [new entrants]”.

Apple’s signing of former Channel 4 and BBC executive Jay Hunt to run the creative side of its European video operation (based in London) sends a clear message to broadcasters that it has serious ambitions here. “They’ve hired a really serious player in this territory,” said the Expectation boss.

“These guys have very deep pockets. Why did [Left Bank’s] Andy Harries do The Crown with Netflix? There was a huge cheque,” said Kate Bulkley.

While Mathew Horseman agreed that Apple, Amazon and Google had huge amounts of money to spend on programming, he was “not so sure that Netflix does have the sustainable cash funds”.

Mike Darcey agreed. “The question is, does Netflix have the business model? You can splash some cash for a while but, in the end, [because] you’ve got shareholders – it’s got to work. Do these new guys have a new model, which allows them systematically to spend more on content? I think the jury’s still out on that.”

Tim Hincks suggested that, “ultimately, it’s not about scale. Scale isn’t what creates hits and tells stories – people do.” But talent would look for “a home where they feel most comfortable” and where “they can get their idea in front of as many eyeballs as possible”.

The true value of viewer data

Kate Bulkley: ‘Data is very important, but it’s not everything – commissioning by algorithm is probably not the way to go – but certainly [it is important] for the advertising business and scheduling [decisions].’

Mathew Horsman: ‘Where it really works is giving a consumer experience that is so much better… search and navigation, deep curation. Personalisation is strong stuff if it’s done well.’

Tim Hincks: ‘I’m not as sceptical about [deals driven by] the algorithm from a creative point of view.’

Mike Darcey: ‘[Data] is second… to the judgement that people make about what makes a great idea.’

Welcome to the new media landscape

A clash of business models

Kate Bulkley: ‘These [technology] companies aren’t in the same kind of business [as] traditional legacy media companies. Studios want to make money by making and selling programmes; Amazon doesn’t care about making money on the programmes that it commissions – it wants to sell more loo roll. It’s a very different business model.’

Global vs local content

Tim Hincks: ‘We talk about demand for global content [such as] House of Cards – and that’s what we’re seeing with these new entrants, the notion of big global pieces.

‘But… they’ve also spotted that people in Britain also like British, local content.… If I was the BBC or Channel 4, that’s the thing I would be getting concerned about right now.’

The end of the co-production era

Mathew Horsman: ‘We’ve seen this trend where the networks [have worked] with the new entrants.… [UK broadcasters] put in a bit of money – the [new entrants] put in a lot of money – and [broadcasters] retain the UK rights and have the first window.

‘That was a trend that built and built to a crescendo, but I think that it’s already over. I think these big, new entrants are saying, “How come we’re giving you a budget of £6m an hour, you’re spending £1m and you’re getting all the UK rights so we can’t show this stuff on Netflix during the same window. We’re not going to do that again.”’

21st Century Fox’s bid for Sky

Mike Darcey: ‘The 21st Century Fox proposal to buy the remaining [Sky]shares that it doesn’t own is well advanced through the Competition and Markets Authority.… I think that the betting has to be that it’s more likely than not to go through, but it’s not a done deal.’

A challenging outlook for UK broadcasters

Mathew Horsman: ‘There are three revenue streams for network television: subscription, licence fee and advertising. All three of those are under significant pressure.

‘Advertising is absolutely under pressure. The licence fee – it will be up to us, but it doesn’t look good. And subscription is not growing for full-fat pay-TV.’

Premier rights: Why did the giants not bid?

Many media commentators argue that UK sports rights, particularly football, are ripe for picking by the US tech giants – but it hasn’t happened yet.

In February, Sky and BT Sport paid £4.464bn for the five main packages of English Premier League matches for 2019-22 – an outcome that suggests that the days of hyper inflation are over.

There are two more EPL packages available, which will permit all 10 matches in a round of fixtures to be broadcast simultaneously, four times during a season.

‘There was so much coverage claiming that Amazon, Netflix and Google were going to bid for [EPL rights], and you look at the results of the first bit of the tender and Sky and BT [won],’ said Mathew Horsman.

Kate Bulkley had expected Amazon to bid for these rights but was unsure whether it would bid for the last two packages: ‘They’re not great packages – it seems to me that probably BT or Sky will end up with them.’

‘They’re pretty poor packages,’ agreed Mike Darcey, adding: “There are probably cheaper and more targeted ways to try to grow the subscriptions of Amazon Prime than spending £5bn on football rights.

‘The [Premier League] is struggling to sell the last two packages. It would appear that it ran an auction and, to the extent that it has received bids for those packages, it is not happy with the level of the bids, so they remain unsold.’

The RTS early-evening event ‘Sale or scale’ was held on 22 February at The Hospital Club, central London. It was produced by Sue Robertson, Jonathan Simon and Martin Stott.