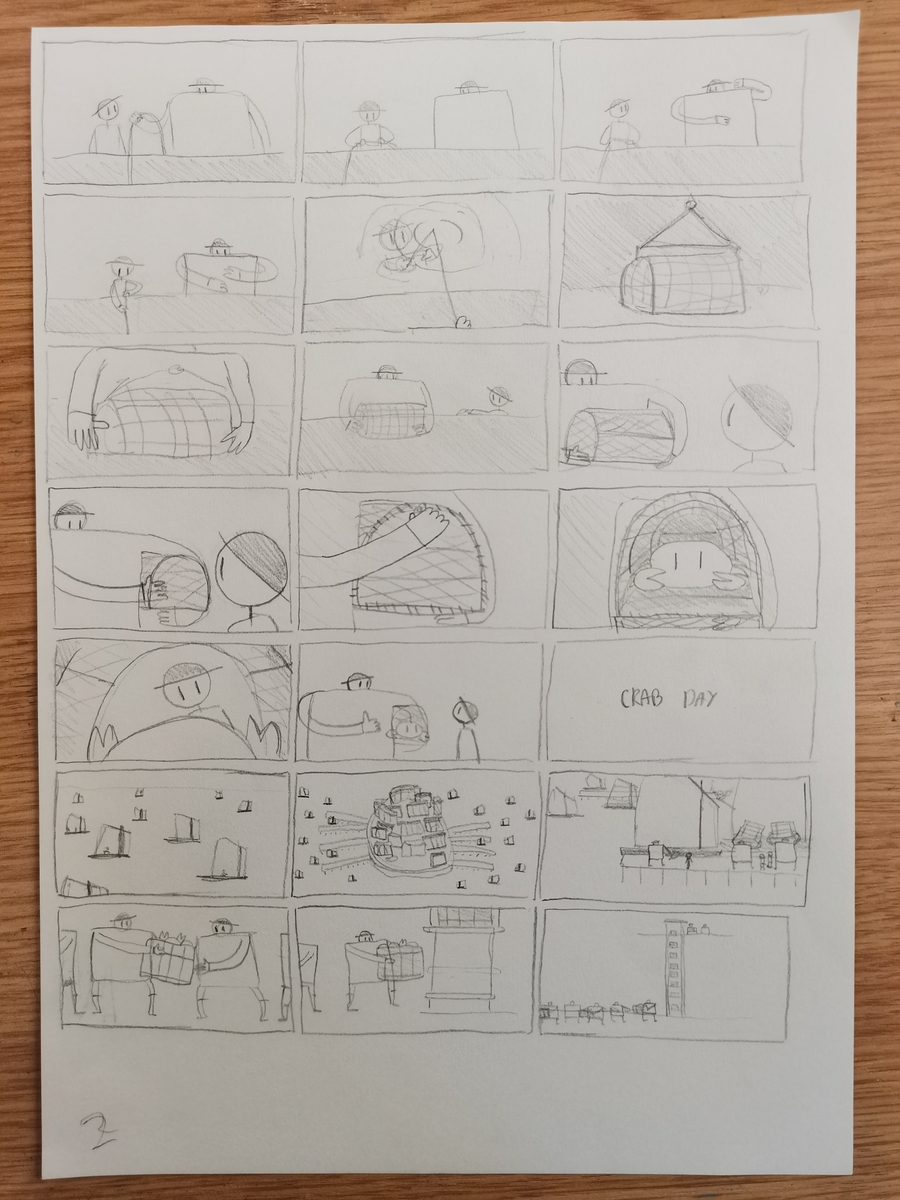

Out of just a few carefully drawn lines, squares and circles, all pencil on plain white paper, emerges a man and a boy fishing from a sail boat.

A father and son fishing for crab, we gather, as the man gifts his catch to the boy in a loving gesture punctuated by a burst of colour. The crab’s orange shell is the only splash of it in this world of monochrome masculine conformity, the intimidating scale of which is illustrated in the mechanical sequence that follows. We see a conveyor belt of countless identical men crab farming, binge drinking and arm wrestling, like cogs in an alpha male machine, while the son looks on, blankly.

“I would just straight up say that I’m the boy and the dad is my dad,” says Ross Stringer, who directed the animated short film, Crab Day, as part of his MA at the National Film and Television School.

Growing up, unlike his older brother, Stringer was more into his art than his sport, and it was because of this, he says, that “my Dad didn’t know how to grab my attention. But he knew I liked being outside in nature, and that translated to, ‘okay, we’re gonna do the man version of that and go fishing’. We learnt to communicate through that.”

Communicating, essentially, by not communicating. Stringer points out that fishing involves “a lot of sitting around and being really quiet,” which made it the perfect metaphor for the kind of taciturn masculinity he wanted to explore in Crab Day.

The title itself refers to the fictional killing ritual, central to the film, whereby boys can only become men by killing a crab. It too comes from a core memory of Stringer’s, albeit one straight out of The Inbetweeners. “We would catch fish and kill them, and to kill a fish you would just grab it and smack its head against the pier wall really hard."

The first time he killed a fish, he recalls, “I didn’t do it hard enough, because I was scared and a little kid and it was still alive. It was really gruesome! And my Dad was like ‘let me do it’, and I was like, ‘no I’m gonna do it!’”

Unlike the young Stringer, however, the boy in the film rejects this rite of passage by saving his crab. Although Stringer does hasten to add that he eventually stopped eating fish and meat altogether.

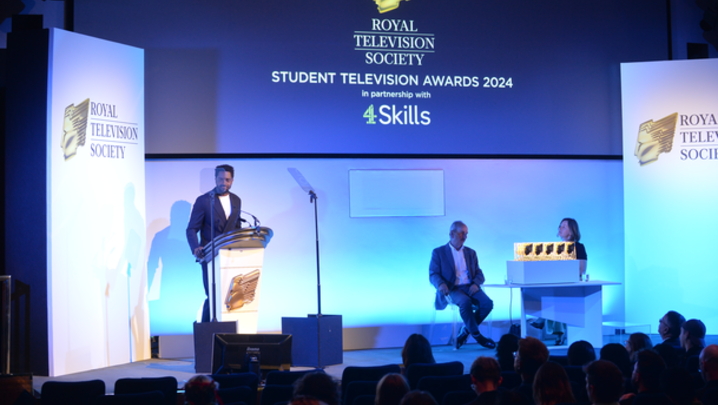

It's a deeply personal story, but Crab Day has resonated across generations and awards juries, winning the Postgraduate Animation category at the RTS Student Television Awards 2024 and proving the old adage that ‘what is most personal is most universal’.

The idea initially came to Stringer during his very first project at the NFTS, which sent him and student writer Aleks Sykulak trawling through the Tate’s online gallery for inspiration. ‘The Crab’, Oskar Kokoschka’s violent World War Two allegory of a monstrous crustacean towering over a helpless swimmer off the Cornish coast, gave them a loose concept. Although it’s obviously a far cry from their own gentle creation.

Another artist they came across was the late fisherman turned painter Alfred Wallis, and his childlike interpretations of his life at sea and in St Ives. Despite the two artists bearing distinct sensibilities, Stringer and Sykulak took Kokoschka’s concept of a ‘monster crab’ and filtered it through Wallis’ naïve style.

“[The style] is a really good way of communicating a child’s perspective,” says Stringer, “and I wanted to express the story through [the boy’s] point of view, almost like the film itself is a child’s drawing.”

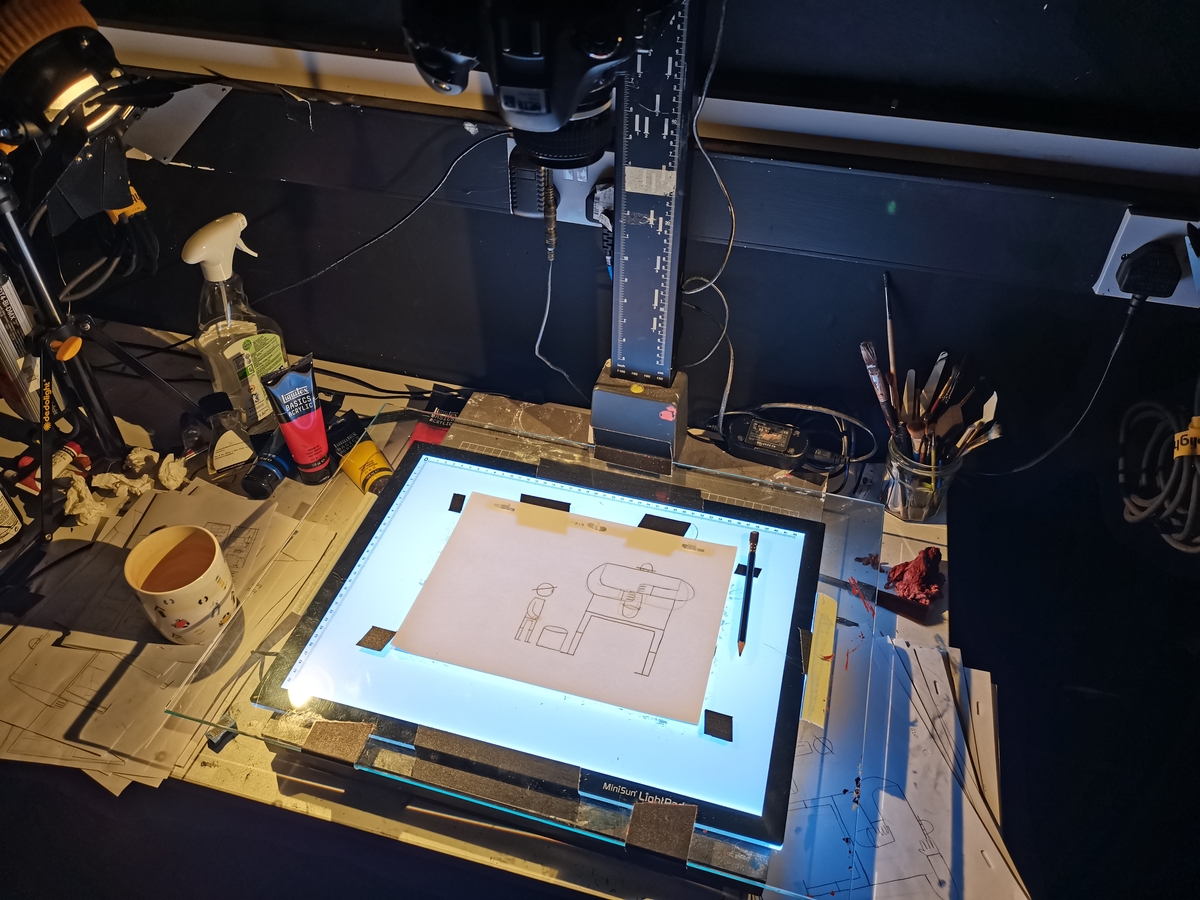

To make your graduate film look like a child’s drawing is, to say the least, an admirable act of creative bravery, and it wasn’t a decision Stringer made easily. He says he kept trying to make it “more and more complicated, and more and more impressive,” experimenting with 3D, stop motion and other techniques. “At the school, you're shown so many impressive films from previous years that use all the facilities to their full potential, so you almost feel this pressure to use them as well."

When it came to the score, for example, student composers at the NFTS are allowed to use an orchestra for a single film of their choosing, and Matteo Tronchin wanted to choose Crab Day. “I was all up for it,” says Stringer, “and then not long after, I realised we didn’t need a full symphony to tell such a simple, innocent story.” Crab Day is about a young boy stumbling to express himself in his own way, which lends itself less to a 3D world braced by a soaring string section than a few scribbles propped up by the plucking of an occasionally off-key violin.

While Tronchin’s score hit the emotional beats (and the virtuoso hit them instantly, according to Stringer, who calls him a “genius”), for a film of such spare detail and zero dialogue, Simon Panayi’s sound design was vital to building a sense of place and self-expression.

Field recordings he made in the Isle of Wight gave Panayi some seaside ambiences to work with, but other sounds required more innovative methods. One of the biggest challenges, he says, was that there were “very limited means for the boy to express himself.” They didn’t want to “just place something into his mouth that wouldn't feel right.” In fact, the boy doesn’t even have a mouth, “so we had to try to do it as non-verbally as possible.”

His ingenious solution lay in software designed specifically for removing the excess pops, clicks and other mouth noises from speech recordings. However, “you can also inverse the output,” he explains, “so the blinks are actually me speaking, but just all of the mouth clicks.” He even matched his intonation to the emotion of the characters to try and nuance each blink.

Through previous collaborations and Crab Day’s constant evolution, the two had developed an almost tacit creative partnership, but Panyi recalls one instance where “I did barge into [Stringer’s] office and was like, ‘the men have to burp’.” There are no women on this island, he reasoned, so there was no need to inhibit what he politely terms their “overt masculine grossness.”

Panayi wanted the adults’ sole means of communication to be belching, but he settled with Stringer for a few precisely placed burps. His favourite? If you listen closely to the puff of smoke as the boys turn into men once they chop their crabs, “there’s a big old burp in that.” As it turns out, this was the clip the RTS played when Panayi won his own award in the Craft Skills – Sound category.

Stringer says he spent "months on end"

The funny thing is, Stringer probably welcomed such office invasions. Upon accepting his RTS award, Stringer thanked his collaborators like Panayi, who joined him on stage, for keeping him sane through the “months on end in a very small dark room drawing this film.” He would later reveal there were times he even thought about dropping out, when none of the styles of the film were working.

All these dark and lonely hours must have made the film’s eventual reception, and all the awards, especially validating. Poitiers Film Festival even flew him out to France to present his short to audiences of all ages and backgrounds, where it was often the kids, he recalls, who asked the most thought-provoking questions. One six-year-old caught him off guard by asking him about the lack of women. (His response: a short film can only communicate so much, and the characters are meant to be symbolic clones).

Equally, he says, “mums liked it a lot,” and a lot of them would approach him after a screening to share their appreciation. He sometimes noticed dads behind them silently nodding along, which struck him as poetically apt.

Which leads us to an important question: what did his dad think of it?

He first saw the film at his grad show, he says, “and it was the moment I think him and my family had respect for what I do. In typical dad fashion, he was very proud and after the [awards] stuff I’d hear from the rest of my family how he would talk about it to other people a lot.

“He’s always taking steps to show his vulnerable side and I think we’ve become closer since.”

If you’ve seen the film, this ending might sound familiar. The final act sees the boy take a stand by cutting loose his now giant crab, thereby forging his own path to manhood. We see them riding away together, only to cut to a close up of the dad, whose unreadable face is made up of nothing more than a wide-brimmed hat and a pair of eyes, like all the men in this town.

But then he lifts his head, and he turns out to be smiling – smiling at the man his son has become.

Crab Day won two awards at the 2024 RTS Student Television Awards, for Postgraduate Animation and Postgraduate Craft Skills - Sound.