Haydn Jones, Account Managing Director at Fujitsu, explains how broadcasters should respond to changing viewing habits.

The question is not where we are now but where we’re headed. In short, what is the end point? That’s the puzzle prompted by Ofcom’s latest report into the UK’s media and communications consumption habits. It’s a puzzle for broadcasters in a world that looks increasingly time shifted, mobile and bite sized.

Ofcom’s Communications Market Report 2015, is the twelfth of its kind and shows further evidence of a trend away from linear-only viewing. It found, for example, that a third of total time spent watching audio-visual content is via non-traditional, non-live methods. We devote three hours and 40 minutes each day on average to watching broadcast television on a TV set. It’s a large number but it is 11 minutes down year-on-year and it marks the third year in succession that there has been a decline in this kind of viewing across all age groups.

The findings are stark although others will point out that real-time, linear viewing is holding up fairly well. We are watching and listening to more stuff in aggregate, the argument goes, so a growth in on-demand, largely internet-based consumption doesn’t necessarily mean a decline in traditional viewing. One is not necessarily cannibalising the other.

The argument has some merit. After all, we still spend more time on average with our TV than with other viewing devices. Yet, dig a little deeper into the numbers and a clear demographic pattern comes into view.

Among adults aged 16 to 24, just half of viewing time is spent watching traditional, live television, much less than the overall average. Meanwhile, the most significant decline in broadcast TV watched on a TV set is among 25-34 year olds (8.8 per cent). As a prelude to future trends, these figures are likely to prove more telling than the 0.3 per cent decline in traditional viewing among the over 65s. Ask where we are heading, and it’s probably best to look at the younger cohorts, not the older ones.

So where does it end? Is there a point at which the numbers will stabilise or does this demographic driver force viewing habits to a moment where all experience of real-time television has been eliminated? How far into the future have we got to go before we reach one of two points – either where nobody is watching real-time TV or the experience of real-time television settles on a residual core of news, current affairs and sport, plus a sprinkling of reality TV thrown in for good measure?

Either scenario raises two concerns for the broadcaster, and the public service broadcaster (PSB) in particular.

The first is what the loss of linear viewing means for community. This potential inflexion point butts up against the premise of TV creating a shared watching experience. From election night coverage and the Queen’s Christmas message to Morecambe and Wise and Only Fools and Horses, the collective experience delivers on a mission to “inform, educate and entertain”. Without those shared moments, what role PSB?

The counter argument to this is to point to the emergence of the virtual water cooler. Spoiler alerts allowing, time shifted viewing doesn’t necessarily mean the end of the shared experience. After all, readers of bestsellers and watchers of blockbusters have long been able to share asynchronous cultural experiences. Social media amplifies this opportunity. So where technology advance threatens the shared experience on one hand, it gives it a new outlet on the other.

The second is concern, perhaps with greater existential implications, is how to ensure ongoing relevance in an on-demand era where broadcast becomes increasingly anachronistic. The traditional PSB may, for example, choose to concentrate solely on news and sport given that they are the genres most diminished when time shifted. That self-selection could indeed become a differentiating factor.

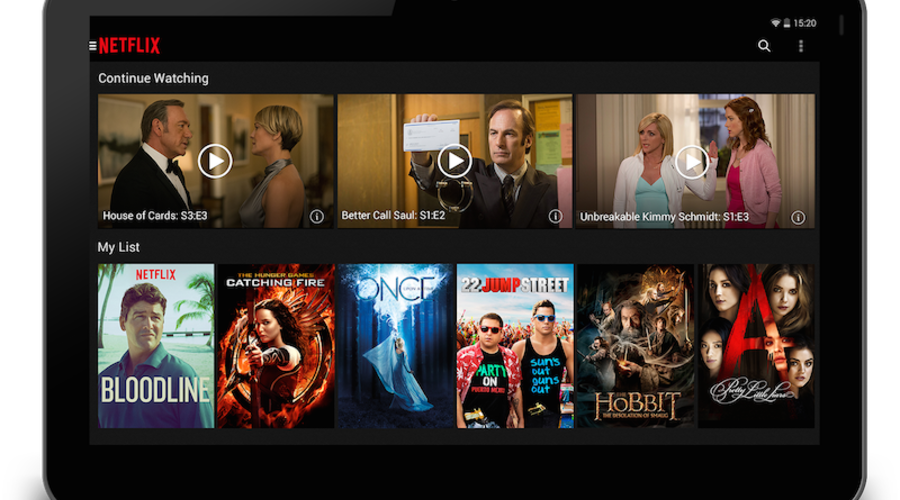

Alternatively – or additionally – the PSB could choose a more radical future. For example, it could make its entire content archive cloud enabled. The offer? Any time, any place, anywhere high quality viewing. The technical implications? Support for real-time, dispersed infrastructure and a metadata-based solution that ensures discoverability.

The latter is an enormous challenge in this unbounded, time shifted world of content. The beauty of broadcast is that you know where to find it – the calendar and the clock are your directory. Online and on-demand things aren’t as easy. How do you provide the guide to unlock it? While acknowledging the scale, impact and success of YouTube, it remains a mess – a big linear creation with problems of categorisation. The PSB solution must be more sophisticated and more intuitive.

The organisation that can solve this digital dilemma will prosper. For a broadcaster wrestling with its ongoing relevance these are the puzzles to be solved.