Bectu Head Philippa Childs highlights remedies to avoid a repeat of the jobs crisis gripping the UK’s TV freelance workforce

The crisis for TV freelances looks set to continue for the foreseeable future. This was one of the conclusions of a sobering lecture given by Bectu Head Philippa Childs to the RTS late last month.

The union leader pulled no punches regarding “the perfect storm” that has engulfed parts of the UK TV sector, especially for those who work on unscripted programmes.

“Industry workers face a particularly challenging environment,” she said. “I’m sure that we all hoped that 2024 would see a recovery, that productions impacted by the Writers Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA disputes would quickly restart and that broadcasters’ commissions would reset.

“It seems, however, that the landscape is much more complicated than that and the impact of the ‘perfect storm’ that Bectu spoke about in the summer of 2023 will stretch far into 2024.”

Last May, Bectu declared an emergency in the unscripted sector as work dried up for freelancers.

The below-inflation BBC licence-fee settlement, announced by the Government in December, and the prolonged advertising downturn have led to a commissioning drought that seemed unimaginable back when production was surging in 2022 following the Covid-induced shutdown.

More than 200 jobs are being lost at Channel 4, reportedly 15% of the workforce, while ITV is subject to a recruitment freeze. At the BBC, Tim Davie and his team have made some tough choices, with cuts to flagship current affairs programme Newsnight and the axing of daytime soap Doctors.

These factors combined with “an increase in the cost of production have taken a huge toll on freelancers who work primarily on broadcaster-commissioned productions. The impact on indies big and small is also very evident,” noted Bectu’s leader. “Progress for SVoDs seems also to have stalled as funding models for streamers have come under similar strain.

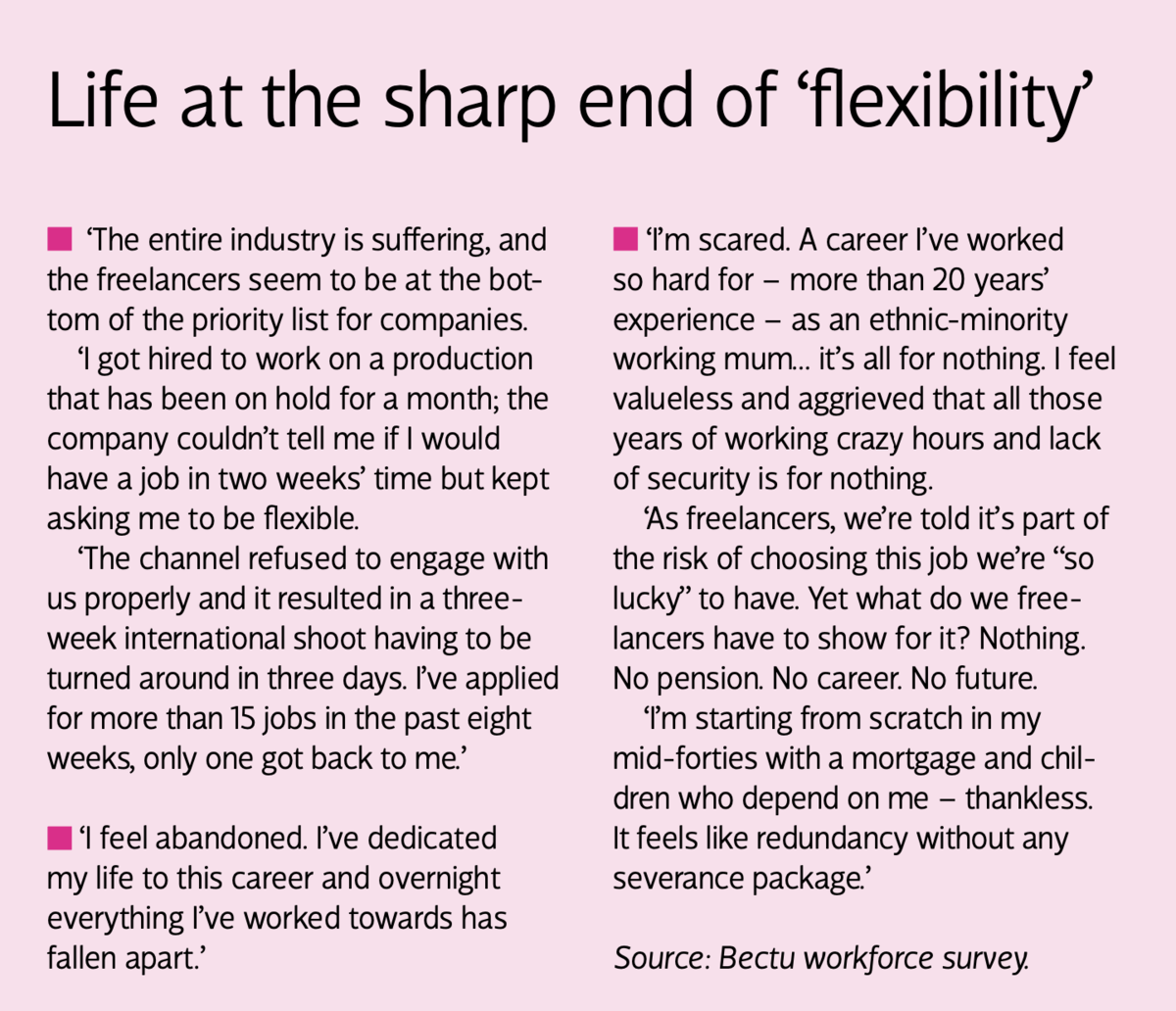

“Bectu recently conducted a follow-up survey to one that we did last summer, and the results make for grim reading [see first box].”

Childs said that “perhaps the most worrying statistic of all, and one that should ring alarm bells for all of us, is the increase in the number of people who are planning to leave the industry within the next five years. From 24% in September 2023 to 37% now.

“This statistic is even more pronounced in the unscripted sector: more than half those working in unscripted TV say they plan to leave the industry.”

Childs continued: “At a recent round table that I contributed to, Adeel Amini [a freelance entertainment producer] said, ‘Freelancers don’t figure in broadcasters’ business models or projections. Everyone feels that we aren’t their problem’. I think that is a sentiment that everyone here who is a freelancer will endorse, and something that was repeatedly raised in responses to our survey.”

She added: “The Film and TV Charity’s recent ‘Money Matters’ report highlighted extreme levels of financial vulnerability among industry workers. Almost half were finding it difficult to manage financially; 42% had less than £1,000 in savings; and 71% were pessimistic or very pessimistic about their financial future.

“Our own survey reflects these findings. More people told us they are unable to pay their household bills than in September, and there has also been an increase in people taking on loans or unsecured debt to cover their bills.

“In the spring and summer of 2023, The Film and TV Charity saw an 800% rise in applications for its stop-gap grants from workers experiencing financial need.

“While, of course, these grants have provided a lifeline for many freelancers – and I cannot praise the charity highly enough for all the brilliant work it does to help support industry workers – I think we have to ask a fundamental question. Is it morally defensible for workers in this industry to have to rely on charitable handouts to survive, when film and TV provides such huge profits and contributes so much to the UK economy? Is that sustainable – or is the model broken?”

The pandemic exposed freelancers’ vulnerability as many fell between the gaps of the various government support schemes.

Childs noted: “The term ‘freelancer’ is used rather loosely in this industry, including by us. How people are engaged largely fits into three categories: those who operate as sole traders; those who work through their own limited companies; and those who are on short-term PAYE contracts…

“So many of those who were on short-term employment contracts were not eligible for furlough because of the relevant qualifying dates and so many people who worked through limited companies fell foul of the rules around the Self-employed Income Support Scheme.”

Childs added: “The whole question of employment status is one that the Labour Party has said it wants to simplify, if it is elected, so that people are classed as either an employee or self-employed. But changing employment status categories from three to two may throw up more questions than it answers, and the real issue is about rights at work for both employees and freelancers.”

Bectu and its parent union, Prospect, have published with the Community union and the Fabian Society a Manifesto for the Self-Employed. It argues for improved working rights, including better sick pay, and for bringing leave and flexibility entitlements for self-employed new parents into line with those of employees.

“We know that many industry workers feel that things cannot go on as they are,” said Childs. “I think it’s more than clear that we are at a tipping point. Something has to change.”

In France, a scheme to help those working in the creative sector was introduced in 1936 to help the film business. This is an unemployment insurance scheme for creative workers who receive state-backed financial help provided they have worked a significant number of hours.

“I mention this only because it is a very clear recognition by the French Government of how precarious the creative industries can be. And because it was one of the schemes that worked well during the pandemic when everyone was effectively given a ‘free year’ and were paid benefits throughout.

“The Irish Government is currently trialling a scheme for a basic income for arts workers to recognise the financial instability faced by many working in the sector.”

Returning to the UK, the Head of Bectu said that “the time for warm words and platitudes has passed and urgent action is needed to halt the drain of skills and talent haemorrhaging from the industry”.

Even when unscripted freelancers were in work, things were far from great – “long working days, few rest breaks and a lack of overtime payments, unrealistic budgets and timelines, rampant burnout, to name just some of the pressing issues”.

Childs called on broadcasters, indies and Pact to reach an agreement with Bectu to regulate working conditions for unscripted workers.

She added: “There are a couple more initiatives currently taking place that may result in positive change. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport has charged the BFI with a project on ‘Good Work’, with an agenda to: strengthen the baseline platform of protection and support for creative workers; drive improvements in management and workplace practices; enhance professional development and progression; and improve creative worker representation.”

In the opening months of 2024, shows such as Mr Bates vs the Post Office, One Day and The Traitors had shown British TV at its best. Childs insisted: “If our industry wants to continue to be the best in the world, and I genuinely believe that we are, then we must all do more to resolve the current crisis and try to address the reasons behind the feast and famine nature of work.”

Report by Steve Clarke. Philippa Childs, Head of Bectu, gave a keynote address to the RTS on 19 February at the Cavendish Conference Centre, London. The producers were Sarah Booth and Harriet Humphries. Max Goldbart, International TV Editor at Deadline, hosted the Q&A. Watch the video here.