David Nicholls is a writer renowned for his relatable fiction.

Over four novels, two of which have been adapted for the silver screen (Starter for 10 and One Day), he has astutely mirrored the average life stages from adolescence to adulthood, often reducing the nation to tears in the process - read One Day at your peril.

Us, he says, was his “midlife crisis novel,” and it’s his latest to get the nod for adaptation as a four-part BBC miniseries, written by Nicholls himself.

“In my head, it was always a slightly downbeat novel,” said Nicholls. “You’re in the mind of someone who’s clearly having a nervous breakdown and that sort of infects every page.”

That someone is Douglas Peterson (Tom Hollander), a tightly-wound biochemist whose wife, Connie (Saskia Reeves), breaks the news that she has been thinking about leaving once their son, Albie (Tom Taylor), flies the nest. Hence the breakdown.

Albie is very much his artistic and free-spirited mother’s son, which has always left Douglas outnumbered by two to one in a clash of fundamental inclinations. Now him and Albie barely speak.

In staunch denial and open to drastic self-change, Douglas seizes the family holiday they had booked as his last chance to restore the ailing marriage and Albie’s affection.

“I think with this we’re hoping that people sit there and go ‘oh my God, it’s us!’,” explained Nicholls.

“It’s about all of those things we don’t confront in our relationships… that are often the reasons why we’re not at ease with our parents or our children.”

As much his own antagonist as he is the protagonist, there are a lot of things Douglas hasn’t confronted, and a lot of things he either should or shouldn’t have said over the years. “But he has that very traditional English problem of not always being as frank as he needs to be,” said Nicholls.

And so, while the family journey through Europe, Us continually flashes back to retrace the demise of the relationship by papercuts. Papercuts that are, more often than not, those things Douglas has said.

"We’re hoping that people sit there and go ‘oh my God, it’s us!’"

A first person journey through a lot of time and places, Us is not an obvious candidate for adaptation.

“I think when you write a first person novel, it’s fine to be in that character’s head and not know everything about the others," commented Nicholls.

“But when you’re in a rehearsal room and someone asks ‘what was my childhood like?’, you have to know or, at least, have to decide.”

In Us, the camera brings an objectivity to what was originally an entirely subjective account. Connie and Cat (Albie’s love interest and holiday crasher, played by Thaddea Graham), for example, are both more sympathetic on screen, explained Nicholls.

“In the novel, Connie’s a little harder and more manipulative, but with Saskia’s intelligence, wryness and spark… it’s still faithful to the book it’s just a little nudge in another direction.”

Even Douglas is made more likeable. “Tom [Hollander] sometimes asked me to dial things down,” said Nicholls.

“The character is pent-up, pedantic and pompous, but that doesn’t mean everything he does has to illustrate that. You can soften it sometimes and have moments of tenderness and humour.”

Being open to such input from actors was one of the essential lessons Nicholls learnt while finding his footing in screenwriting, especially when working on the classic UK sit-com, Cold Feet (“my real baptism of fire”).

“Sometimes you do have to put your foot down but generally if an actor is uneasy with something there’s normally a good reason. And even if their solution isn’t right their problem is probably valid.

“So I like to keep actors happy and not in a cynical way but because it’s better to watch people having fun rather than people struggling to say things.”

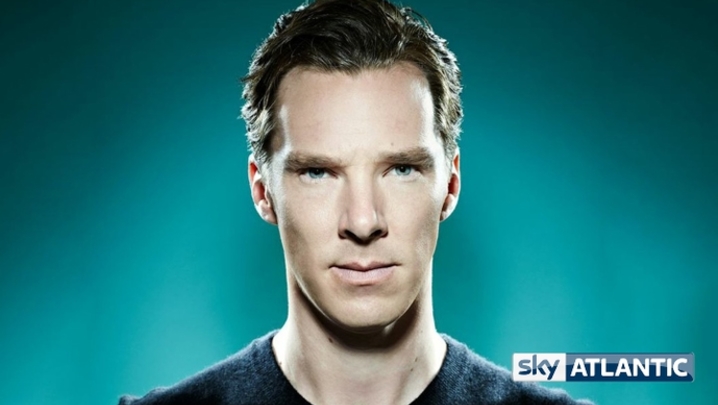

Actors have certainly thrived in parts written by Nicholls, and none more so than Benedict Cumberbatch in his adaptation of Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose.

Cumberbatch starred as the titular Melrose, who, over the span of five decades, wages war on his addictions and inner demons with deep roots in abuse by his tyrannical father and neglectful mother.

“There is a flamboyance to Patrick’s decadence and bad behaviour,” Nicholls said. “He’s the shit and he knows he’s the shit, but it comes from a terrible place.”

It was a surprisingly dark tonal shift for the primarily romance writer, and he believes he wouldn’t have got the job if the decision had been based purely on One Day and Starter for 10.

“I’d just done Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Winterberg and that had a slightly harder edge to it, so I think that persuaded them that I wasn’t always going to soften things or make a joke at the wrong moment,” he explained.

"Because [Patrick Melrose] was a redemption story, I felt I could draw that out without compromising the books, and make it tough but touching in a way that wasn't sentimental."

'Tough but touching' reads like a mission statement for most of Nicholls' work, including Us, which also shares that same suspicion of sentimentality. Douglas Peterson himself is hard-edged, stricken with a severe realism and caustic wit, but as Nicholls said, like Patrick Melrose, he is ultimately just "someone struggling to be decent."

"A page of prose can become completely unnecessary because of something an actor does with their face"

"There’s always a reason for us at our worst - I don’t know if I believe in born villains.”

Douglas' struggle is palpable throughout, due in part to the stylistic blueprint that Nicholls and director, Geoffrey Sax, settled on for the series.

“We wanted it to look beautiful but not picture postcard, so you do feel the sweat and strain as the trip falls apart with a kind of lyrical quality.”

A quality that is intensely felt from the outset, as when Douglas retreats to the dump, his ‘fortress of solitude’, after Connie shares her wish to split. In a slow motion sequence soundtracked by Mozart, he rips and kicks his waste cardboard to pieces in operatic despair.

It is the perfect embodiment of Nicholls’ favoured voice, equal parts comedy and pain, perhaps amplified by his first ever lengthy stay in the edit suite alongside series film editor, Carmela Iandoli.

“The edit suite is another place to write for me, especially with the way pacing can be altered,” explained Nicholls.

“You can’t make any changes to the way a reader reads a novel, enforcing a certain pace or stops at certain points, but in the edit you’re trying to produce a universal experience, speeding up and slowing down time.”

Although, as Nicholls notes, often a single shot conveys all, owing to the on screen talent.

“A page of prose can become completely unnecessary because of something an actor does with their face, which is just extraordinary.”

Us continues this Sunday 11 October on BBC One at 9pm.