Carole Solazzo examines the splintered world of children’s TV, talking to the kids about what they watch and the parents who make the shows

Hands up everyone who was told off for watching too much television. And hands up who watched Why Don’t You Just Switch Off Your Television Set and Go and Do Something Less Boring Instead?, the BBC One series that ran between 1973 and 1995. Irony, dead? It was slaughtered, stuffed and displayed behind glass half a century ago.

But what about today’s children? If the primary school pupils of St Peter’s in Newchurch, Lancashire, and Holly Mount in Bury are anything to go by, television viewing is still popular.

I asked the headteachers of the two schools, which are attended by my granddaughters, if I could come in and chat with different year groups and their teachers to find out what programmes these children watch and enjoy.

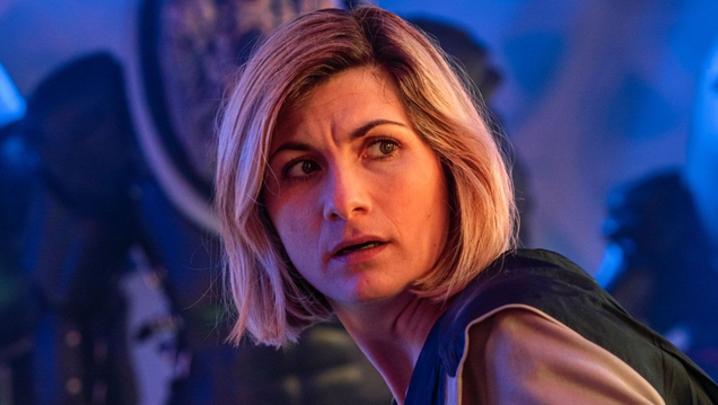

Children aged between six and nine watch TV with their families: Bake Off, Strictly and Doctor Who; sport, too. They like shows about the natural world, such as Planet Earth, and anything about dinosaurs. Many watch shows with younger siblings – but don’t recognise the names of terrestrial channels CBeebies or CBBC, streaming the shows instead.

Some children watch other children play games such as Minecraft on YouTube because they like to see the children’s reactions, and they pick up tips on how to play the games.

By Years 5 and 6 (ages nine to 11), though, the number of children watching television has fallen, and much more content is consumed on TikTok, YouTube and other platforms. They like watching children play computer games, unbox toys and enjoy stunts by the likes of MrBeast.

"Home-grown kids' TV is exceptional"

They still enjoy shows about the natural world and sport and watching Saturday night TV with their families, but many of these children have “graduated” to watching content intended for an older demographic. The Simpsons on Disney+, Channel 4’s Young Sheldon and Brooklyn Nine-Nine are popular, as are scarier shows such as Wednesday and Stranger Things on Netflix; plus factual programmes such as Save Our Squad with David Beckham on Disney+.

Naturally, many people working in TV are also parents. Those with older children note that the outlook is even less rosy for traditional networks. “My boys don’t watch terrestrial channels, they watch YouTube,” says Terri Dwyer, producer at indie Buffalo Dragon and the mother of teenage boys. “You can’t stem that flow now… but the terrestrials need to bring back particularly the older young audience.”

VFX artist on CBBC show Andy and the Band Jonathan Shine, a father of teenage girls, agrees: “I’ve seen the transition away from kids’ TV to YouTube.” And it matters, he says, because “kids’ TV, like great kids’ literature, is educational”. He sums up the best children’s TV as “magic, morals and mischief”.

“Home-grown kids’ television is exceptional,” says production designer Mitch Silcock (Henpocalypse!, Andy and the Band). “You get a lot of moral guidance from TV. Do you want them watching YouTube, which is just selling them products repeatedly, with no story, no message and no journey?”

He continues: “We have an obligation to make sure that we’re delivering wholesome messages, lessons learned about teamwork or relationships, and in ways we would like all children to carry forward as grown-ups.”

Dwyer believes: “It is really important to ensure that storytelling reaches a young audience.”

“As a designer,” says Silcock, “the word I always use is ‘aspirational’. [Children] don’t want to see recreated the world as they perceive it. They want to see a world they would love to live in.… If you’re showing a school on TV, you want the kids watching to be desperate to go to that school.”

“VFX are definitely the ‘magic’,” says Shine. “They look great, and they’re fun, adding the garnish to a perfect plate.” Moreover, “VFX can help children understand narrative… attract their attention to a certain part of the screen, stimulate the child visually to help them understand something.”

Prop-maker Martin Hall also aims to stimulate children’s imaginations: “It’s about shapes, unnatural bright colours, the way things move. Is [the gadget] similar to things like animals or robots? Then, if it’s a ‘good’ prop that does something playful, give it a smiley face or add more curves and soft edges.”

There are many challenges in making live-action children’s TV and Dwyer picks some out: “[Children] can only be on camera for a certain amount of time. They need breaks. You have to bank schooling into your budget if they work for a number of days.”

Some children’s shows are low budget. Despite that, however, according to director Jordan Hogg (Ralph & Katie, The Evermoor Chronicles), Evermoor was “wildly ambitious. What made it easy to film was that it was Disney. Every morning, literally everything had to be run through the company and nailed. That negated any possible problems, and you could really focus what you spent your money and time on – and be creative.

“From a director’s point of view, directing kids is very different from directing adults,” Hogg continues. “It’s about helping them enjoy the experience, keeping a fun atmosphere, playing games to keep their energy up.”

He talks about the duty of care to children in emotional scenes, and “if I want a child to look ‘in thought’ and I know they like football, I’ll get them to think about what squad their manager will put out this weekend. It gives the same outside expression of thought while they’re thinking about something they can relate to.”

How do you get these shows in front of children? Dwyer says: “We’re seeing a massive growth in AVoD [ad-supported video-on-demand] such as YouTube. Pre-Covid, the thought of putting your programmes free on the internet would have been a horrifying proposition, but the blue-chip companies are realising that there’s an awful lot of eyes on the free streamers – so playing their ads on those service is more beneficial perhaps. If you want to scoop up that younger audience, that’s where they are.”

Dwyer’s sons watch a lot of science shows but, she says, they don’t watch documentaries. “So, not only are we trying to access eyes, but the way we are positioning and naming our content is important,” she observes.

“The trick that is missing in children’s drama is event telly,” believes Hogg. “[Children’s TV] needs to get everyone round the telly at once, like when Doctor Who came back or Merlin started on BBC One.”

Furthermore, he suggests: “I couldn’t tell you at the moment what’s on CBBC or any of the kids’ channels because it’s not put in front of the adults. They need to advertise to a wider demographic so that the parents think, ‘That looks interesting’, then put it on and encourage their children to watch – rather than expecting the kids to pick up the remote and put it on.”

Marshall McLuhan, the 1960s communications guru, argued in his groundbreaking work The Medium Is the Message: “We shape our tools, and then our tools shape us.”

Mass communication, as disseminated by the television set, he posited, would create a “global village” and a worldwide conformity of thought processes.

But will the many screens and countless content platforms now do the opposite, splintering the world into fragmented units where content comes at you fast and indiscriminately? As William Empson says in his poem “Let It Go”: “The more things happen to you the more you can’t tell or remember even what they were.”

Will a different way of viewing lead to children processing their thoughts in different ways from everyone else? And, therefore, do our children need to watch not less TV but more kids’ TV?