UK broadcasters are against pooling TV as sales, but there are other ways to co-operate, explains Gideon Spanier

Broadcasters need to be “more aggressive” in pitching the value of TV to advertisers, and they should produce joint research to prove it, argues Ruth Cartwright, head of audio-visual media for Amplifi, part of agency group Dentsu Aegis Network.

“The challenge for broadcasters is that, despite all the evidence that we know to be true – that TV maximises campaign reach, increases awareness and delivers a competitive return on investment – advertisers and, frequently, media planners undervalue TV,” she explains.

A huge, heated marquee at a holiday campsite in Hampshire might seem like an unlikely venue to champion the future of TV advertising. But, back in February, that was where ITV, Channel 4 and Sky came together for the inaugural Big TV Festival, an event aimed at wooing 150 young marketers and media planners over two days.

Ros King, director of marketing communications at Lloyds Banking Group, described to the audience how Halifax’s TV ads featuring cartoon characters from Top Cat had been so effective. The bank kept bringing them back, running them in seven bursts over two years.

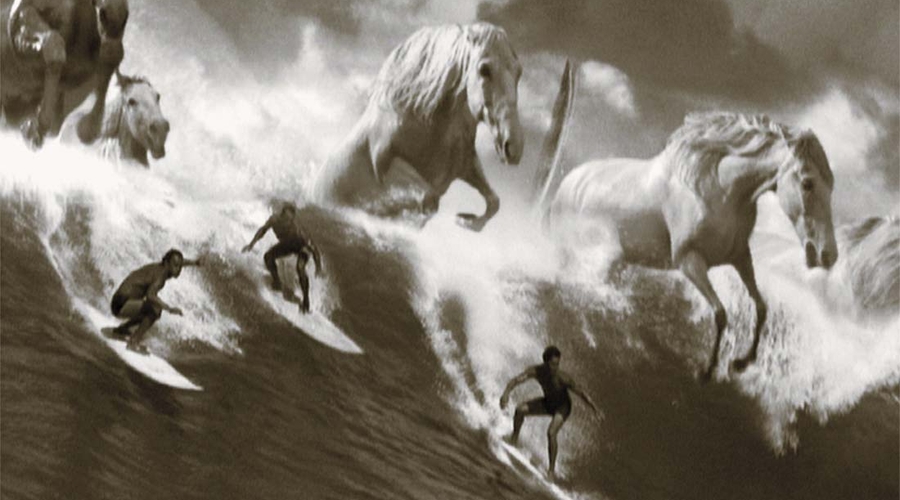

Chaka Sobhani, chief creative officer of ad agency Leo Burnett, and Rosie Arnold, head of art at fellow agency AMV BBDO, showed their favourite TV ads, such as the Guinness surfers and Yeo Valley’s rapping farmers. And Rory Sutherland, Vice-Chair of Ogilvy and a Spectator columnist, warned about the perils of online advertising in a barnstorming speech that celebrated the importance of making brands famous.

The Big TV Festival was such a significant event for the UK ad industry because the three leading commercial broadcasters showed that they were willing to unite at a time when online platforms, such as YouTube, Facebook, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, are growing fast.

"Annual TV ad revenue in Britain has risen from £4bn during the nadir of the financial crisis in 2009 to a peak of £5.2bn in 2016"

“The world is getting more competitive from a global perspective,” Jonathan Allan, Channel 4’s chief commercial officer, told the gathering. He explained why he and his counterparts at ITV and Sky felt it was important to “speak more with one voice” and to “get more visible, together externally selling TV”.

Broadcasters have not faced the same structural declines that newspaper and magazine publishers have suffered, as advertisers’ money has migrated to the internet giants. “Emotional” ads by brands such as John Lewis have shown that TV still has unrivalled mass, simultaneous reach and an ability to “connect” with consumers in a way that tech platforms cannot match.

What’s more, targeted TV advertising, services such as Sky AdSmart, offer growth opportunities for video on demand (VoD).

Annual TV ad revenue in Britain has risen from £4bn during the nadir of the financial crisis in 2009 to a peak of £5.2bn in 2016. Following a slight dip after the Brexit vote, it is forecast to be up marginally, at just over £5bn, in 2018, according to GroupM, the media-buying agency arm of WPP.

By contrast, national newspaper ad revenue has nearly halved from £1.3bn to £750m over the same period. It took until 2016 for newspapers to put aside their rivalries and look at pooling print and digital ad sales to make it easier for advertisers to buy from them.

The initial talks, called Project Juno, collapsed but News UK, publisher of the Sun and the Times, Telegraph Media Group and Guardian Media Group agreed on a more modest proposal this summer to set up a joint venture, the Ozone Project. It will pool their digital display ad inventory and audience data.

Agencies welcomed the initiative as a small step in the right direction, but industry watchers think publishers should have acted sooner. Enders Analysis warns that the situation is akin to climate change, in that “a meaningful response” could come “too late”.

Broadcasters are determined not to make the same mistakes as publishers when it comes to collaboration. However, for several reasons, pooling TV ad sales is not on the agenda.

First, the TV market is governed by the contract rights renewal (CRR) legislation introduced after the merger of Carlton and Granada in 2003. These rules protect advertisers from ITV abusing its position as the dominant player in TV ad sales.

Enders Analysis has warned that CRR is anachronistic, because it encourages trading by share of ad spend on TV, rather than volume, in a world where advertisers have lots of video options beyond TV. However, Carolyn McCall, ITV’s new Chief Executive, has ruled out a challenge to CRR because she fears a “regulatory mire”.

The second reason not to pool TV ad sales is that the market works reasonably well and efficiently. In 2003, there were 10 TV sales houses. They have since merged into three main players: ITV’s share is about 45%, while Channel 4 (which also handles sales for UKTV and BT) and Sky (which looks after Viacom, Discovery, Fox and others) each have about 27%. That contrasts with newspapers, where there are still seven national sales teams.

Tess Alps, Chair of Thinkbox, the marketing body for commercial TV, says: “TV sales is now consolidated to quite a great extent and the market seems to be happy with that.”

There are other ways to collaborate, particularly around VoD, audience data, technology and content. Setting up the equivalent of the Ozone Project as a joint venture for VoD advertising (leaving aside regulatory hurdles) could have merit.

"Agencies are also pushing broadcasters and video platforms to adopt technology that makes it easier to serve ads in a standardised way, instead of having lots of different software"

While there is no great demand for change in traditional TV ad sales, “the world of data-driven, VoD TV, where you have to invest an awful lot of money in technology and know-how, is where you start to have very interesting conversations about how you can work together”, according to Jakob Nielsen, Chief Executive of Finecast, Group M’s VoD ad-buying platform.

Ruth Cartwright adds that advertisers would like a high-quality alternative

to Google and Facebook that has no ad fraud, is brand-safe and has scale. “I do think that any route to creating easily accessible premium content on a joint [advertising] platform would be a good proposition,” she says.

Sky’s AdSmart platform is already used by brands and agencies to target viewers by demographic and location on that broadcaster’s channels and online; its revenues rose 29% last year, albeit from a low base.

ITV and Channel 4 have each held on-off talks with Sky for years about joining AdSmart, but have been unable to agree commercial terms.

Even if the broadcasters won’t pool ad sales, they could share audience data. Sources say that ITV and Channel 4 are looking at how they could create a shared VoD data platform.

Agencies are also pushing broadcasters and video platforms to adopt technology that makes it easier to serve ads in a standardised way, instead of having lots of different software.

Finecast, which launched last year, allows advertisers to serve VoD ads on 15 different types of device. These include Sky and Virgin Media set-top boxes, Roku and Chromecast streaming devices, Samsung connected TVs and Xbox gaming consoles. “I can’t explain how difficult and how complicated it has been and how long it has taken us to do that,” Nielsen says.

The explosion in the number of devices has been good for TV because it means there are more opportunities to view content and advertising. But broadcasters are also having to grapple with immense structural change, as consumers have more power to skip ads and are willing to pay for premium, ad-free, global services such as Netflix.

Suddenly, UK public service broadcasters look small by comparison with international rivals, raising questions about whether the British creative industries could be at risk. This has prompted the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 to discuss plans for a joint, online streaming platform for British content. They have been given encouragement by Ofcom – a nine years after regulators blocked a similar idea, Project Kangaroo, on competition grounds.

The imminent sale of Sky to Comcast or Disney shows that broadcasters can no longer just think local as they battle the tech giants. In a small, but symbolic, move, Channel 4 has set up a joint digital sales venture, the European Broadcaster Exchange, with Germany’s ProSiebenSat, France’s TF1 and Mediaset in Italy and Spain, to attract international advertisers – a growing issue when Google and Facebook offer global ad sales.

If the golden rule with advertising is to follow the money, then there should be no doubt that the future is greater collaboration.

Gideon Spanier is global head of media at Campaign.