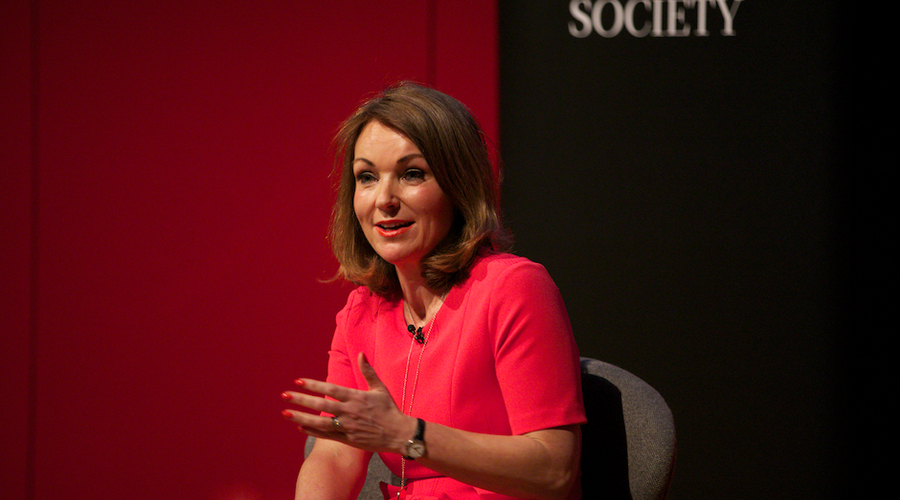

Chief Creative Officer Jay Hunt explains how she helped reinvigorate her channel by nurturing an inclusive commissioning culture

I want to give you a very personal view of what it’s been like trying to change the culture at Channel 4 from the inside out. Five years ago, I walked over the glass bridge at Horseferry Road to start my job. It’s easy to forget what Channel 4 looked like then.

It had always been an iconic brand that resonated with young audiences. A buzz word for innovation and mischief making.

But it was also battered and bruised. The recession had hit it hard – 20% of headcount had been wiped out. On air, it could be schizophrenic. Two hundred hours of Big Brother cast a long shadow. Factual had to fly the flag for the remit. To top it all, the creative team was famously cliquey.

A snapshot supplier survey done just before I arrived made hair-raising reading. Channel 4 was still the indies’ champion, but the indies were falling out of love with a broadcaster that they accused of cosy deals with former commissioners and a closed-shop culture that concentrated spend on a favoured few.

Roll forward five years and where are we now? Today, Channel 4 is positively bullish. No Big Brother, no begging bowl, no busted business ventures.

So, how has it changed? Well, most obviously, we’ve worked with brilliant people who’ve had brilliant ideas and made them into brilliant TV. Writers, directors, producers and editors, all delivering their very best work for C4.

But we’ve also changed the way we work. Why? Because anyone in TV knows that what we all do is a form of insanity. The roulette wheel at a seedy Vegas casino has better odds than picking hit shows.

When I arrived at C4, I realised we needed to shift the odds. To put it another way, we needed to bring some science to the art of being creative. And there was some urgency. I remember the blood draining from my face when I first read the lofty remit I signed up to.

Creative organisations present a particular conundrum because they’re built on the notion that ideas are king. Many people still subscribe to the view that the televisual equivalent of the artist in the garret is the only real custodian of creative thinking.

But can we really build a billion-pound business on the promise of something that incalculable? We tend to romanticise what we do. There’s even a clue in the title. We call ourselves the creative industries, implying that people in other industries do something that isn’t creative.

But, of course, this tortured wrestling with ideas is universal. There are brilliant case studies from companies as varied as Twitter and Dyson. The themes are the same: how do you structure to improve your chances? How do you tolerate and nurture maverick thinking but still deliver at scale?

My then-Channel Executive, Ed Havard, was sent on a management course in LA. It was designed to foster new ways of thinking. He’d seen lots of companies but one had really impressed. It’s almost a cliché in creative circles now to cite Pixar, particularly after Ed Catmull’s excellent book Creativity Inc. But, back then, its unique way of working was less well known here.

The Pixar culture is built on robust peer review. At its heart, the organisation is defined by a belief that decision-making is better when it draws on a collective knowledge.

One of the central tenets of the Pixar model is the Brains Trust. It’s basically a posh name for a meeting of the top creative team. It was set up during the making of Toy Story, with a purpose that could have come straight from the mouth of one of their own superheroes.

It was tasked with “rooting out mediocrity”. It became a forum to tease and test a concept in a safe, supportive environment. That might sound like any old meeting you go to, but the difference here is the willingness to be honest.

"I remember the blood draining from my face when I read the lofty remit I signed up to."

Catmull’s mantra was simple but incredibly hard to deliver. He said: “Candour is the key to collaborating effectively. Lack of candour leads to dysfunctional environments.”

And I knew all about those. I’m a strange control experiment all of my own. As the only person to have run channels at 4, 5 and the BBC, I’ve seen several broadcasting cultures up close. Collaboration was not one of their defining behaviours. And nor, frankly, was candour.

All of them paid lip service to honest peer review, with big meetings inspirationally labelled “programme reviews”. These were studies in political game playing that would have put the Borgias to shame. At 4, that behaviour was even more marked.

David Abraham recounts a funny story of his first meeting with the commissioning heads of department before I arrived at 4. They all took their seats expectantly. David kicked off by asking how often they normally met as a group.

One of them, who still works here, piped up: “Well, we never really meet like this.” It was against this rather unpromising backdrop that we started to work in a different way. We would be a different sort of broadcaster. A team working in partnership with indies to improve our collective chances.

I started by organising two-hour meetings twice a week with my own team. We couldn’t manage it consistently. Now we meet every week, first thing on a Tuesday, for 90 minutes. It’s called “the breakfast” but that’s a misnomer: the only sustenance is coffee. We discuss everything and anything.

What should our response be to the growing number of unemployed young people? What would it look like if we took this germ of an insight and planted it over there? How do we capture the current disaffection with conventional politics?

Three years on, it’s become a powerful forum for finessing ideas. Imagine a focus group of people, who genuinely get TV, trying to work out how to get your show on air. And that’s it. No one in the room has any other motivation for being there. They’re not incentivised to help. They don’t have a financial stake in success. They’re just trying to make the good, better. Creatively, it’s become like turning to a clever friend.

And, critically, it’s changed what’s on air. Take The Island, a fantastic piece of work delivered by Shine – but the commissioners at 4 did help shape what it would become. In that instance, the breakfast added value. Because what’s not to like about getting some additional brainpower on cracking a show?

I’ve always found the idea of a channel controller sitting there like Nero, giving a thumbs up or thumbs down on a recommission, to be rather cartoonish.

It’s even more so now, when data has given us so many tools to help spot what might work. Did social media leap on the show? Were the audience appreciation scores high? Did it deliver the perfect tick the scheduling team are looking for, where a show launches well, possibly drops off but then grows again?

Metrics help when you are selling a vision to parts of a creative business that needs to make the uncertain certain.

Let me be clear what this strategy is not, though. It’s not a short cut to the moment of magic that leads to great TV. In a world where Netflix and Amazon tell me that they can predict what I will watch, I am a refusenik.

"Being more pragmatic about failing has ensured that we have succeeded."

You can’t run the numbers for surprise or feed my viewing habits into a big machine and tell me I will like something I never even knew existed. The creative flair in this room is still what ignites the flame. To extend the analogy, looking for clues in the data is how we manage to keep the flame alight.

We’ve stood shoulder to shoulder with other indies to grow shows. First Dates became a hit after we bloody mindedly refused to give up on it. Similarly, The Last Leg went from struggling to get an audience of more than 1 million to delivering double digit young share and audiences over 2 million.

So certain am I that we need more input into our creative conversations at 4, not less, that the breakfast meeting I hold with my heads of department has been rolled out to the whole of my team and beyond.

Once a week, there are at least nine different groups of people kicking around ideas. The team who write our press listings and run our presentation desk have joined in, too. We’ve even got people from sales in the mix.

In any given week, more than 100 people at 4 are discussing what we could put on the telly. In time, I hope that people from all over the company will become part of this quiet revolution, because they force us to think differently.

And forcing us to think differently has led to a higher number of shows that feel genuinely original. It’s also made us work faster, particularly in genres where mass audience taste is so hard to call. Comedy is a great example.

Helped by the breakfasts, Catastrophe was recommissioned before it was aired. Flowers, our brilliantly dark new comedy drama, was championed in the room not just by my talented Head of Comedy, Phil Clarke, but by our Head of Documentaries, Nick Mirsky.

If it all sounds a bit People’s Republic of Channel 4, it’s not. You can’t churn through the decision-making needed to commission thousands of programmes across a portfolio of channels by putting every decision to a vote. In the end, like channel controllers everywhere, I have to decide and be accountable to David and the board. But those decisions are now informed by the most inclusive commissioning process I’ve ever been part of.

So, five years on, these are the things I know. Creativity can be led by teams, not just individuals. Risking failure ensures you succeed. Different perspectives colliding sparks real originality.

I also know that I’ve been lucky. Lucky because I’ve had the luxury of being able to experiment. For starters, I’ve had a boss who understands creative risk-taking. David gets it. He’s been at the coalface himself. He knows that you’ll only win if you try and then keep trying.

Not having to deliver a profit has allowed us the space to fail. And being more pragmatic about failing has ensured that we have succeeded. In the maelstrom of political noise we are living through at the moment, maybe it needs spelling out even further. I am absolutely certain that we would not have achieved what we have achieved in private hands.

I know now that 4 can be just as innovative off air as it can on air. Five years on, it’s a different kind of broadcaster. A place where brilliant indies work with commissioners who are talented producers themselves to make unmissable shows – shows that move the dial not just here but globally.

At its best, I believe Channel 4 can rival the greatest creative organisations in the world. And, let’s face it, who wouldn’t want to be part of that.

This is an edited version of a speech by Channel 4 Chief Creative Officer Jay Hunt at the event ‘Five years at 4: building a creative culture’, which was held at the British Museum on 15 March and produced by Martin Stott.