Chris Chibnall, feted for Broadchurch and the new showrunner on Doctor Who, shares insights into his working life with Mark Lawson

Most people, asked to identify the show that changed the career of Chris Chibnall, would point to his ITV crime trilogy Broadchurch. But, for Chibnall, the show that altered everything was, unusually, a flop: Camelot, his king-and-wizard drama for the US cable network Starz, which struggled to the end of one season in 2011.

“Very early in my career,” says Chibnall, “someone told me that you learn more from a failure than you do from a success. And then I lived out that phrase for a year in Los Angeles. I learned that I would not work that way again or be put in that situation again.” The essential lesson was: “You either have to be in total control of a show or working with people who share your vision and will work with you to achieve it. Also, never work with 13 executive producers.

“Camelot was the classic case of too many cooks. It wasn’t a harmonious set-up and I think that does manifest itself on screen.

“I had a fantastic cast but you have to be free to tell the story you want to tell in the way that you want to tell it. What ended up on screen was not what I wanted and so it is a blemish on my CV.”

Chibnall is speaking from Cardiff, where he is doing early work (“some meetings, and measuring the curtains and so on”) for his next project, as showrunner of Doctor Who from 2018.

Although Chibnall has form with the franchise (having written five Doctor Who episodes and seven of the spin-off Torchwood), he was picked as successor to Steven Moffat after showing an ability to deliver big ratings and major tension between 2013 and 2017 on Broadchurch.

And that landmark series would never have happened without the catastrophe of Camelot.

The director James Strong visited Chibnall on the Arthurian lot, when they were working on United, a 2011 BBC Two drama (written by Chibnall and directed by Strong), a bio-drama about the Manchester United team destroyed in the Munich air crash. “Camelot was obviously agonising and difficult for him,” recalls Strong. “He was suffering all of the American producing clichés of interference. And I think that he desperately wanted to do something that was just his.”

That was Broadchurch, which was directed by Strong. In an intriguing insight into Chibnall’s working methods, he says: “We sat in a pub after finishing United and I said, ‘What are we going to do next?’ And Chris said: ‘We’re going to do another film. But this one will be eight hours long.’

“Chris wrote a draft. I went to Dorset and walked the cliffs with him, trying to get the identity of the place into the scripts. We worked on it for a few months. Then, he sent it to ITV and they replied within 24 hours, saying, ‘This is amazing!’”

Although Broadchurch is now fixed in the history of television, Chibnall says that it is important to him that “each of the three series was a different kind of risk”.

In the opening season, the jeopardy was spreading a single murder story over eight weeks: “This was a time when episodic, story-of-the-week drama was seen as the way to go.

“So the notion that you would have one story over eight weeks was high-risk. The Killing had done it as a critical and industry hit for a loyal and discerning audience.

“But we were doing it in ITV peak time, with the risk that there would be no one watching by week 2 if it didn’t catch on, and we’d end up being shunted to 11:30pm on Saturday night.”

The gamble in the second series (which many reviewers and viewers considered lost) was whether the original narrative could be revisited from the fresh perspective of a trial.

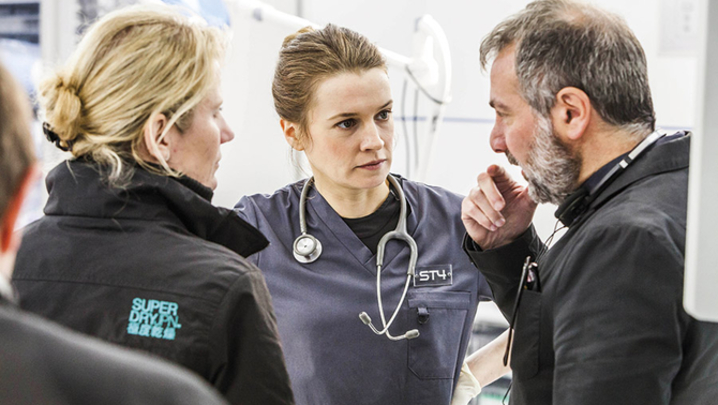

In this year’s run, the more successful creative bet was whether a closed-community crime drama could tell the story of a rape investigation. Chibnall further raised the stakes by making the bulk of the first episode a three-hander drama-doc-style depiction of best practice in the investigation of sex crime.

Along with Jed Mercurio’s Line of Duty (a rival Chibnall much admires), Broadchurch has pushed back hard against the assumption that TV fiction is moving inevitably towards self-scheduled binge-watching.

Chibnall and Mercurio have proved that viewers will willingly be left on a cliff edge for seven days, with the frustrated anticipation and speculation becoming part of the fun.

“I think people still want appointment television,” says Chibnall. “Especially at certain points in the week. Sunday night is one of them, so moving Line of Duty to Sunday night was a master stroke. And Monday night on ITV is another one: I was thrilled to get that slot because that was the night that Cracker and Prime Suspect were on.

“For all that we binge-watch and catch-up, communal viewing has survived on those two nights in particular.”

But, for such a show to work, do future plot twists have to be ruthlessly protected from viewers and newspapers? “Yes. It is quite difficult. The only way to do it is not to tell anyone, which isn’t possible because lots of people need to know how to do their jobs.

“You have to have security measures in place. Scripts are electronically distributed; everyone has individual passwords. You have to foster a team mentality and hope that people will want to protect the endeavour.

“I’m interested that Twin Peaks has taken it to the absolute zenith by not even having trailers. But the definition of a good story is being told things that you don’t know yet.”

Strong, who first worked with Chibnall on Torchwood, remembers how, “by the second series of that, Chris became a sort of showrunner. So he always had a producing hat on.”

Subsequently, Chibnall has taken on ever more responsibilities, so that he now operates as a writing executive producer, with Jane Featherstone as a non-writing executive producer. “I feel my job is to set the creative vision,” he says. “I think of it as curating a team of geniuses.”

Does Chibnall, though, feel free to write, “a fleet of B-52 bombers lands on the aircraft carrier”, or is his producing brain already raising logistical or economic objections?

“That’s a key question. I think, in the first draft, the writer should always win over the producer. Your job is to dream and tell the story in the best way that story wants to be told,” he says. “It’s very dangerous, as a writer, to police yourself too much in the early drafts. Because the thing I’ve learned as a producer is that the things that you think will be incredibly difficult are often achieved easily, and the things that you think will be simple are often the most complicated on the day.

“Sometimes, it’s more difficult to throw a chair through a window than to have an alien horde descend on a planet.” That chimes with Woody Allen’s comment that the main creative influences on movie-making are weather and parking permits.

Chibnall laughs: “Yes. You would be surprised at how many locations on TV are decided by the question: ‘But where are we going to park the trucks?’”

Strong, as one of Chibnall’s most frequent collaborators, says: “Chris makes it look so easy. You meet him and sit with him and he’s so relaxed. And very collaborative and open.”

Does he have a stern and shouty side? “I’ve never heard Chris shout. He has a very gentle and considered style. But he knows what he wants and, if he doesn’t like something as a producer, he’ll say it.

“He has a very clear vision of what the show should be. But that’s a good thing. He’s a very good creative leader. He makes sure that everyone in every department is making the same show.”

Strong says that he is “a mixture of surprised and not surprised” that Chibnall accepted the Doctor Who job: “I know what a big fan of the show he is and I know how much he feels he has a vision for it.

“Any reticence would be about the scale and length of the commitment. It’s a five-year project. That was a huge decision. He’s in his absolute prime and could have done whatever he wanted, writing-wise. It’s an absolutely wonderful result for Doctor Who. I think Chris, essentially, writes emotional thrillers, and that’s perfect for that show.”

Chibnall admits that he took a long time to commit: “I finally said yes because I love the show to my bones. I resisted it for a very long time, and [the BBC] really had to woo me.

“But, in the end, I had ideas about what I wanted to do with it. When I went to them and said, ‘This is what I would do’, I actually expected them to say, ‘Ooh, let’s talk about that’, but they said: ‘Great!’”

Chibnall can’t reveal yet what his daring conceit for the series is but would he, for example, be allowed to do a whole-series storyline, like Broadchurch, rather than individual episodes? “Yes. What the BBC was after was risk and boldness.” But he couldn’t kill the Doctor off in episode 1? “Ha! Then the title would really make sense.”

There is a torrent of media and social-media advice about who the new Doctor (replacing Peter Capaldi) should be, and what he or (as many are keen) she should do. But Chibnall says: “I don’t read any of that. One of your jobs as a writer is to cut out the noise. All you have is your instincts and your process. The BBC came to me because they wanted those, and so reading coverage about the show is fundamentally useless and bordering on counterproductive.

“A TV show isn’t a focus group. It is great that people are speculating about who the Doctor will be… but it won’t affect in any way what we do with the show.”

Chibnall’s general tone suggests that there may be a radical revamp of Doctor Who, which will please those who have suggested the show needs a kick up the Tardis.

Strong says: “Well, my own completely personal view is that it does. It used to be – and I stress this is my personal opinion – at the heart of the schedule, an unmissable family show and, for some reason, it’s slipped a bit from the national consciousness.

“For me, when it goes towards storylines that are a little bit more for the fans, I think you can lose that general appeal. I think Chris is going to offer a slightly different take on what the show should be.”

Whatever vision Chibnall has was enough to persuade him to change the course of his career: “Jane Featherstone and I had a new idea and were close to pitching that. So the hardest thing was going to Jane and saying, ‘Look, I may be going to Cardiff for a few years.’

“I have plans for more theatre, more TV. But the amazing thing about Doctor Who is that you can go anywhere and do anything.”

His producer brain quickly kicks in: “Within budget.”