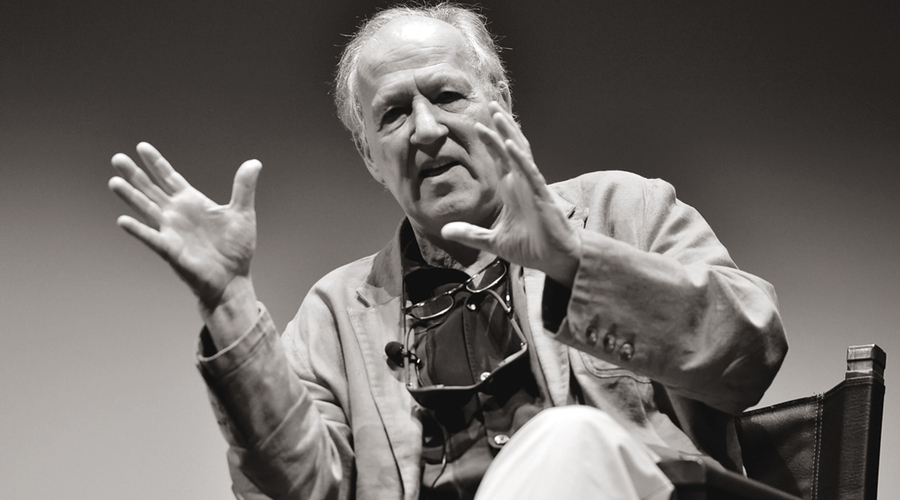

Werner Herzog tells Pippa Shawley how he met Bruce Chatwin, the subject of his latest film – and why lock picking is an essential skill

For a straight-talking man, it’s hard to define Werner Herzog. “Legend” is perhaps the easiest way to describe the 76-year-old, at least based on the reverential whispers that run around Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre ahead of his appearance at the city’s annual DocFest. Best known as the writer, director and producer of more than 60 films, Bavarian-born Herzog is also an author, actor and opera director.

Herzog’s vision is unique – his 1982 film Fitzcarraldo saw him persuade his crew to haul a 340-ton steamship over a Peruvian mountain; in Grizzly Man he used footage shot by Timothy Treadwell to document his experience of living with bears, including the audio of Treadwell being eaten alive by one; he pulled a gun on his notoriously difficult protagonist Klaus Kinski during production of Aguirre, the Wrath of God; and ate his own shoe after losing a bet for Les Blank’s short film, Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe.

Herzog’s work rate is enviable, particularly for someone who claims he doesn’t have a career. He insists he isn’t a workaholic. He’s made three films in the past 12 months: Meeting Gorbachev, featuring a series of interviews with the last leader of the Soviet Union; Family Romance, LLC, a surreal drama about a Japanese firm that loans actors to serve as surrogate figures, such as absent fathers and funeral corpses; and Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, the BBC Arena film that he’s in Sheffield to promote.

“I work in a very leisurely fashion, but [with] concentrated, short days of shooting, very little time editing,” Herzog explains over coffee (black, with sugar). He doesn’t shoot coverage (different shots and angles of the same scene that can be used in post-production) “which everybody spends endless days [doing]”. On average, he spends just nine days editing a film. A screenplay takes him a week to write.

(Credit: Sky/MMV Lions Gate Films, Inc)

An icon of cinema, he’s often asked for his tips to young film-makers: “I try to encourage them to become self-reliant, and stick to their own culture and stick to their own vision,” he explains. “Today, you can make a narrative feature film in theatrical quality for under $20,000.”

The auteur also runs the Rogue Film School, where he spends time listening to students’ ideas and helping them overcome obstacles. “The only two things that I literally teach are lock picking and the forging of documents. Nothing else.”

He can still use those skills today: “[If] I’m crossing the Alps, for example, and there’s a lot of chalets, holiday homes that are only occupied for five weeks during the entire year, I would open them with tiny surgical tools, silently and without any damage… and sleep in the bed when there is a rainstorm out there.”

When it comes to planning his work, Herzog has no problem compartmentalising his ideas, nor in finding new ones. “Normally, projects come with great vehemence at me, very often uninvited burglars in the middle of the night.” He doesn’t carry a battered notebook around to save these ideas because “when somebody is coming wildly, swinging at you in the middle of the night, you better deal with that one first.”

His latest film, Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, was commissioned by BBC Arts’ Mark Bell to mark 30 years since the death of the renowned travel writer and novelist. Chatwin was a close friend of Herzog’s. The pair worked together on Cobra Verde, Herzog’s film adaptation of Chatwin’s novel The Viceroy of Ouidah. The novel was one of only six books published by Chatwin before he died with Aids, aged just 48. He is perhaps best-known for his debut, In Patagonia, and his 1987 work, The Songlines.

“It’s a pity that he didn’t have enough time in his life to do much more,” Herzog laments.

Chatwin wrote about his friend in his essay Gone to Ghana: “He was, I discovered, a compendium of contradictions: immensely tough yet vulnerable, affectionate and remote, austere and sensual, not particularly well-adjusted to the strains of everyday life but functioning efficiently under extreme conditions.”

Herzog remembers being stunned by Chatwin’s ability to tell stories non-stop. “And I mean non-stop, until the day was over, deep into the night, then a few hours’ sleep.

“We would meet at breakfast and he would continue the half-finished sentence from the evening before.”

The pair met in Australia, where Herzog was preparing his feature film When the Green Ants Dream, and Chatwin was researching his book The Songlines, about the country’s aboriginal people.

“I think both of us were searching for each other,” says Herzog. “It was like two critical masses heated up to [make] something much bigger.”

"Everything that had relevance in the last half century or so, even longer, originated [in California]"

Nomad sees Herzog follow in his friend’s footsteps, as he travels to the Australian Outback, Patagonia and the Black Mountains in Wales, carrying Chatwin’s rucksack, which was given to him following the writer’s death.

It was a deeply personal journey for Herzog, who visited Chatwin just days before he died. Towards the end of the documentary, the film-maker talks about the moment his friend told him he was too weak to carry his rucksack. Herzog offered to carry it for him. It is a moving scene for the viewer, but Herzog insists that it isn’t emotional.

“When you say emotional, I immediately think about TV sentimentality, these men crying when they think about difficult times,” says Herzog in his signature German drawl. “It’s rampant, I can’t stand it.”

For any particular reason? “It’s just an abomination, that’s it.”

Herzog avoids this sentimentality by being laconic, “as I was when Bruce was dying.… He was literally only a skeleton and glowing eyes,” he remembers. “The first thing he said to me was, ‘Werner, I’m dying.’

“And I said to him, matter of fact, ‘Bruce, I can see that.’ So it was not a tearful sort of sentimental encounter with someone who was close to me and seeing him die. It was laconic and not sentimental.”

during the making of Nomad (Credit: BBC)

The resulting film is not a straightforward biography of Bruce Chatwin, but is inspired by their friendship, shared worldview and the mutual interest in nomadic peoples that originally brought them together in Australia.

The pair also bonded over their common belief in the power of making long journeys on foot.

“He was also the only person with whom I could have a one-to-one conversation on what I would call the sacramental aspect of walking,” wrote Chatwin. “He and I share a belief that walking is not simply therapeutic for oneself but is a poetic activity that can cure the world of its ills.”

What would Chatwin have made of the 21st century? Herzog thinks for a long time. “I have not thought about this but, of course, he would have been a writer with 20, 30 books finished by today.… We can only speculate, but we know we would have much, much more great literature.”

Today, Herzog lives with his wife, Lena, a photographer, in Los Angeles. It’s a surprising choice for someone who eschews conventional filmmaking and many aspects of modern life. He doesn’t have a mobile phone, isn’t on social media and chooses reading and cooking over watching television.

“I’ve always been curious about the world, and living in Los Angeles has something grandiose about it because it’s certainly the city with the most substance in the US, if not the entire world.”

It’s not often you hear the city where Barbie dolls were invented and the coroner’s office has a gift shop named Skeletons in the Closet talked about in this way. But Herzog argues that LA is the nerve centre of this century’s technological advances.

“I’m not speaking of the glitz and glamour of Hollywood,” he explains. “Everything that had relevance in the last half century or so, even longer, originated there, including the internet, video games… [and] stupidities like aerobic studios.… Almost everything of real importance comes from California.”

It’s hard to disagree. In fact, it’s hard to disagree with much Herzog says, although it’s tricky to tell if that’s because he’s right about everything, or if it’s the effect of his hypnotic, heavily accented intonations that have bewitched viewers for almost 60 years.

Arena: Nomad – In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin will air on BBC Two this autumn. It was written, directed and narrated by Werner Herzog and commissioned for BBC Two and Arena by Mark Bell. The executive producer for BBC Studios was Richard Bright.